Surprise (self-information)¶

The sequences

have exactly the same probability for a fair coin:

So why does one feel shocking and the other boring?

How would you describe the sequence to a friend?

Frame problem in terms of micro and macro states.

A measure of information (whatever it may be) is closely related to the element of... surprise!

has very high probability and so conveys little information,

has very low probability and so conveys much information.

If we quanitfy suprise we will quantify information

Addititivity of Information¶

Knowledge leads to gaining information

Which is more surprising (contains more information)?

E1: The card is heart?

E2:The card is Queen?

E3: The card is Queen of hearts?

Knowledge of event should add up our information:

We learn the card is heart

We learn the card is Queen

A logarithm of probability is a good candidate function for information!

What about the sign?

This quantifies surprise or self-information associated with one specific event or microstate with probability

Why bit (base two)¶

Consider symmetric a 1D random walk with equal jump probabilities. We can view Random walk = string of Yes/No questions.

Imagine driving to a location how many left/right turn informations you need to reach destination?

You gain one bit of information when you are told Yes/No answer

To decode N step random walk trajectory we need N bits.

Shannon Entropy and Information¶

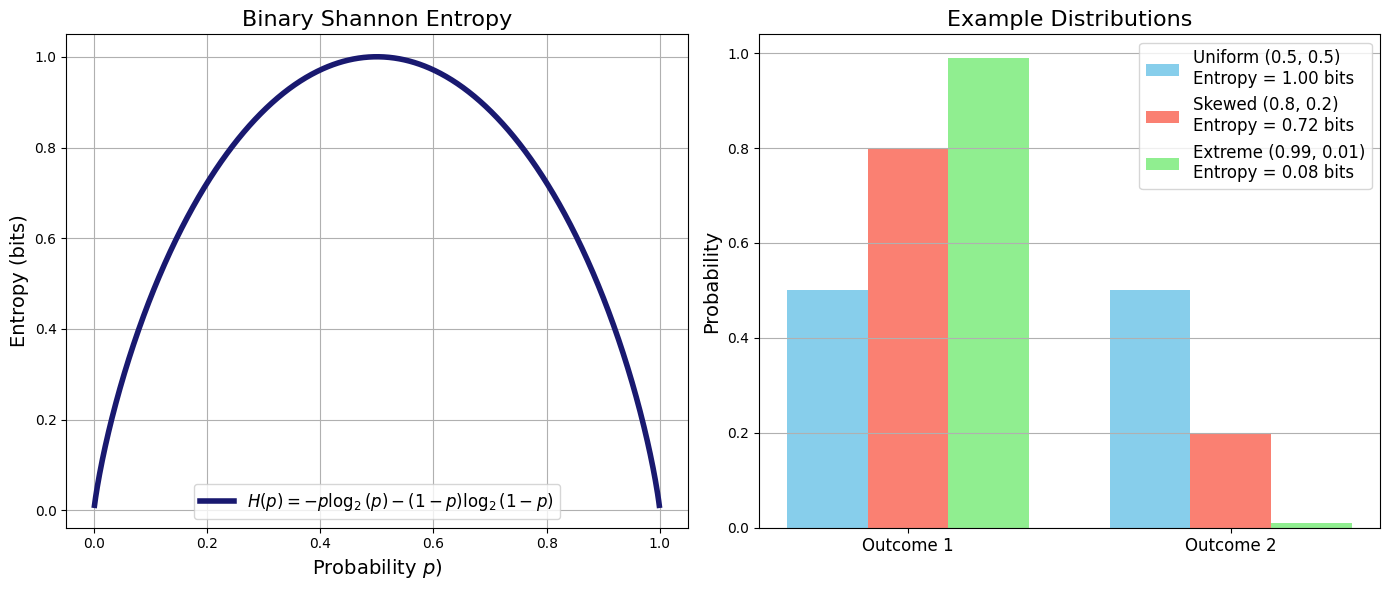

If we want to understand the overall uncertainty in the system, we need to consider all possible outcomes weighted by their probability of occurrence.

This means that rather than looking at the surprise of a single event, we consider the average surprise one would experience over many trials drawn from .

Thus, we take the expectation of surprise over the entire distribution arriving at a formula known as Shaonon’s expression of Entropy.

One often uses to denote Shanon Entropy () and letter with for entropy in units of Boltzman constant

For now lets just roll with we wont be doing any thermodynamics in here.

John von Neumann advice to [To Calude Shanon], "You should call it Entropy, for two reasons. In the first place you uncertainty function has been used in statistical mechanics under that name. In the second place, and more importantly, no one knows what entropy really is, so in a debate you will always have the advantage.”

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def binary_entropy(p):

"""

Compute the binary Shannon entropy for a given probability p.

Avoid issues with log(0) by ensuring p is never 0 or 1.

"""

return -p * np.log2(p) - (1 - p) * np.log2(1 - p)

# Generate probability values, avoiding the endpoints to prevent log(0)

p_vals = np.linspace(0.001, 0.999, 1000)

H_vals = binary_entropy(p_vals)

# Create a figure with two subplots side-by-side

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 6))

# Plot 1: Binary Shannon Entropy Function

ax[0].plot(p_vals, H_vals, lw=4, color='midnightblue',

label=r"$H(p)=-p\log_2(p)-(1-p)\log_2(1-p)$")

ax[0].set_xlabel(r"Probability $p$)", fontsize=14)

ax[0].set_ylabel("Entropy (bits)", fontsize=14)

ax[0].set_title("Binary Shannon Entropy", fontsize=16)

ax[0].legend(fontsize=12)

ax[0].grid(True)

# Plot 2: Example Distributions and Their Entropy

# Define a few example two-outcome distributions:

distributions = {

"Uniform (0.5, 0.5)": [0.5, 0.5],

"Skewed (0.8, 0.2)": [0.8, 0.2],

"Extreme (0.99, 0.01)": [0.99, 0.01]

}

# Colors for each distribution

colors = ["skyblue", "salmon", "lightgreen"]

# For visual separation, use offsets for the bars

width = 0.25

x_ticks = np.arange(2) # positions for the two outcomes

for i, (label, probs) in enumerate(distributions.items()):

# Compute the Shannon entropy for the distribution

entropy_val = -np.sum(np.array(probs) * np.log2(probs))

# Offset x positions for clarity

x_positions = x_ticks + i * width - width

ax[1].bar(x_positions, probs, width=width, color=colors[i],

label=f"{label}\nEntropy = {entropy_val:.2f} bits")

# Set labels and title for the bar plot

ax[1].set_xticks(x_ticks)

ax[1].set_xticklabels(["Outcome 1", "Outcome 2"], fontsize=12)

ax[1].set_ylabel("Probability", fontsize=14)

ax[1].set_title("Example Distributions", fontsize=16)

ax[1].legend(fontsize=12)

ax[1].grid(True, axis='y')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

To reiterate once again from Shannon formula we see clearly that Entropy is a statistical quantity characterized by the probability distribution over all possibilities.

The more uncertain (unpredictable) the outcome the higher the entropy of the probability distribution that generates it.

Source

import numpy as np

import scipy.stats as stats

import matplotlib

# Create figure and axes

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(10, 8))

# Define x range

x = np.linspace(-5, 5, 1000)

# Define different distributions

distributions = {

"Flat (Uniform)": stats.uniform(loc=-2.5, scale=5),

"Gaussian (Normal)": stats.norm(loc=0, scale=1),

"Narrow Gaussian": stats.norm(loc=0, scale=0.5),

"Exponential": stats.expon(scale=1)

}

# Plot distributions and annotate entropy

for ax, (name, dist) in zip(axes.flatten(), distributions.items()):

pdf = dist.pdf(x)

ax.plot(x, pdf, label=name, color='black')

ax.fill_between(x, pdf, alpha=0.2, color='gray')

# Compute differential entropy

entropy = dist.entropy()

ax.text(0, max(pdf) * 0.8, f"Entropy: {entropy:.2f}", fontsize=12, ha='center')

ax.set_title(name)

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.legend()

# Adjust layout and show plot

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Exercise: Information per letter to decode the message

Let represent the letters in an alphabet. For example:

Korean: 24 letters

English: 26 letters

Russian: 33 letters

The information content associated with these alphabets satisfies:

The information of a sequence of letters is additive, regardless of the order in which they are transmitted:

Question If the symbols of English alphabet (+ blank) appear equally probably, what is the information carried by a single symbol? This must be bits, but for actual English sentences, it is known to be about 1.3 bits. Why?

Solution

Not every letter has equal probability or frequency of appearing in a sentence!

Exercise: entropy of die rolls

How much knowledge we need to find out outcome of fair dice?

We are told die shows a digit higher than 2 (3, 4, 5 or 6). How much knowledge does this information carry?

Solution

Exercise: Monty Hall problem

There are five boxes, of which one contains a prize. A game participant is asked to choose one box. After they choose one of the five boxes, the “coordinator” of the game identifies as empty three of the four unchosen boxes. What is the information of this message?

Solution

Exercise: Why are there non-integer number of YES/NO questions??

Explain the origin of the non-integer information. Why it takes less than one-bit to encode information?

Solution

We have encountered a fraction of bit of information several times now. What does it imply in terms of number of YES/NO questions. That is becasue in some cases single YES/NO question can rule out more than one elementary event.

In other words we can ask clever questions that can get us to answer faster than doing YES/No on every single possibility

999 blue balls and 1 red ball. how many questions we need to ask to determin the colors of all balls? bit or 0.01 bit per ball. Divide the container by 500 and 500 and ask where the red ball is? 1 questions rules out 500 balls at once.

Entropy, micro and macro states¶

When all number of microstates of the system have equal probability the entropy of the system is:

We arrive at an expression of Entropy first obtained by Boltzmann where thermal energy units (Boltzman’s) constant were used.

Entropy for a macrostate A which has number of microstates can be written in terms of macrostate probability

Entropy of a macrostate quantifies how probable that macrostate is!. This is yet another manifestation of Large Deviation Theorem we encountered before

Flashback to Random Walk, Binomial, and Large Deviation Theorem

Probability of a macrostate of (n gas particles out of N landing in right hand side of container):

where is the total number of microstates.

When we took the log of this we called it entropy but why?

Here, represents the fraction (empirical probability) of steps to the right in a random walk.

is the entropy per particle (or per step), while is the total entropy.

Connection to the Large Deviation Theorem

When we express probability in terms of entropy, we recover the Large Deviation Theorem, which states that fluctuations from the most likely macrostates are exponentially suppressed:

This result highlights how entropy naturally governs the likelihood of macrostates in statistical mechanics.

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.animation import FuncAnimation

from IPython.display import HTML, display

# Render inline (web) as HTML/JS

plt.rcParams["animation.html"] = "jshtml"

# -----------------------------

# Gas-in-a-box animation (2D) + live macrostate histogram

# -----------------------------

rng = np.random.default_rng(0)

# Box

W, H = 1.0, 1.0

divider_x = W / 2

# Particles + dynamics

N = 400

dt = 0.01

speed = 0.55 # increase for faster motion

frames = 900

interval_ms = 30

# Initialize particles (start mostly on LEFT to show mixing)

x = rng.random(N) * (0.45 * W)

y = rng.random(N) * H

theta = rng.random(N) * 2 * np.pi

vx = speed * np.cos(theta)

vy = speed * np.sin(theta)

# Macrostate tracking: nL(t)

nL_history = []

maxN = N

# histogram bins for nL = 0..N

bin_edges = np.arange(-0.5, N + 1.5, 1.0)

centers = np.arange(0, N + 1)

# -----------------------------

# Figure

# -----------------------------

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4.2))

gs = fig.add_gridspec(1, 2, width_ratios=[1.1, 1.4])

ax_box = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 0])

ax_hist = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 1])

# Box plot

ax_box.set_title("2D gas in a box")

ax_box.set_xlim(0, W)

ax_box.set_ylim(0, H)

ax_box.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax_box.axvline(divider_x, lw=2)

ax_box.set_xticks([])

ax_box.set_yticks([])

scat = ax_box.scatter(x, y, s=10)

txt_box = ax_box.text(0.02, 1.02, "", transform=ax_box.transAxes, va="bottom")

# Histogram plot

ax_hist.set_title(r"Histogram of $n_L$ over time (macrostate occupancy)")

ax_hist.set_xlabel(r"$n_L$")

ax_hist.set_ylabel("count")

counts0 = np.zeros_like(centers, dtype=int)

bars = ax_hist.bar(centers, counts0, width=0.9, align="center")

ax_hist.set_xlim(-1, N + 1)

ax_hist.set_ylim(0, 10)

txt_hist = ax_hist.text(0.02, 0.98, "", transform=ax_hist.transAxes, va="top")

# -----------------------------

# Helper: Shannon entropy of the *empirical* macrostate distribution P(nL)

# -----------------------------

def shannon_entropy_from_counts(counts):

total = counts.sum()

if total == 0:

return 0.0

p = counts[counts > 0] / total

return float(-(p * np.log(p)).sum())

# -----------------------------

# Animation update

# -----------------------------

def update(frame):

global x, y, vx, vy

# Free-flight

x = x + vx * dt

y = y + vy * dt

# Reflect at walls (elastic)

hit_left = x < 0

hit_right = x > W

vx[hit_left | hit_right] *= -1

x = np.clip(x, 0, W)

hit_bottom = y < 0

hit_top = y > H

vy[hit_bottom | hit_top] *= -1

y = np.clip(y, 0, H)

# Update scatter

scat.set_offsets(np.column_stack([x, y]))

# Macrostate: how many on left?

nL = int(np.sum(x < divider_x))

nR = N - nL

nL_history.append(nL)

# Histogram of nL over time

hist_counts, _ = np.histogram(nL_history, bins=bin_edges)

for b, h in zip(bars, hist_counts):

b.set_height(h)

# Autoscale histogram y

ymax = max(10, int(hist_counts.max()) + 2)

if ax_hist.get_ylim()[1] < ymax:

ax_hist.set_ylim(0, ymax)

# Compute "entropy" of macrostate occupancy (empirical Shannon entropy)

S = shannon_entropy_from_counts(hist_counts)

txt_box = ax_box.text(

0.02, 0.96,

"",

transform=ax_box.transAxes,

va="top",

fontsize=10,

bbox=dict(facecolor="white", alpha=0.7, edgecolor="none")

)

txt_hist.set_text(rf"steps={len(nL_history)} $S=-\sum P(n_L)\ln P(n_L)={S:.3f}$")

return (scat, txt_box, txt_hist, *bars)

ani = FuncAnimation(fig, update, frames=frames, interval=interval_ms, blit=False, repeat=False)

plt.close(fig) # avoid duplicate static figure in notebooks

display(HTML(ani.to_jshtml()))

Animation size has reached 21015388 bytes, exceeding the limit of 20971520.0. If you're sure you want a larger animation embedded, set the animation.embed_limit rc parameter to a larger value (in MB). This and further frames will be dropped.

1. Entropy as Information¶

Entropy measures the information required to specify the exact microstate of a system. Equivalently, it is the number of binary (yes/no) questions needed to uniquely identify that microstate.

Examples include specifying:

the full trajectory of an (N)-step random walk,

the detailed molecular configuration of a gas.

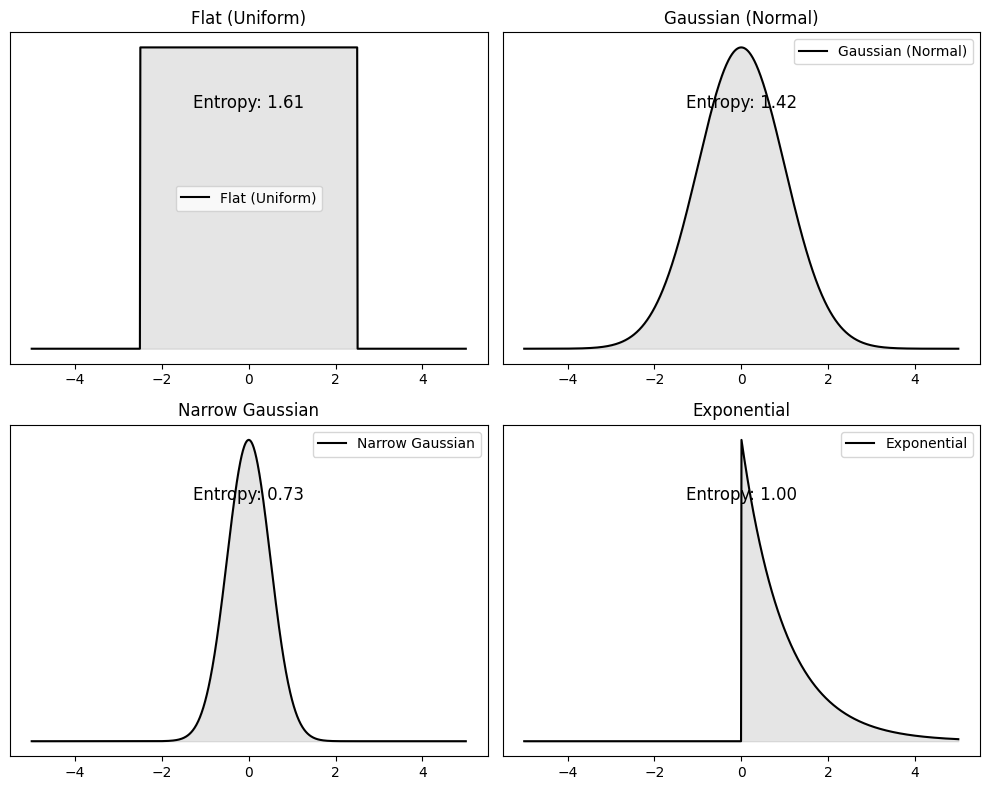

2. Entropy as Uncertainty¶

Entropy quantifies uncertainty over microstates.

Broad, uniform distributions over microstates correspond to high entropy.

Narrow, concentrated distributions correspond to low entropy.

When all microstates are equally likely,

where is the number of accessible microstates.

Systems naturally evolve toward macrostates with higher entropy because these correspond to overwhelmingly more microstates and are therefore statistically favored.

3. Physical Meaning¶

High entropy means that many microstates are consistent with the same macrostate, making the exact microstate hard to identify.

Lowering entropy requires physical work, such as compressing a gas to reduce the number of accessible configurations.

In isolated systems, entropy tends to increase, reflecting the statistical bias toward more probable macrostates.

This statistical tendency is the content of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

Is Information Physical?¶

Maxwell’s demon controlling the door that allows the passage of single molecules from one side to the other. The initial hot gas gets hotter at the end of the process while the cold gas gets colder.

Maxwell’s Demon:

Maxwell’s Demon is a thought experiment that challenges the second law of thermodynamics by envisioning a tiny being capable of sorting molecules based on their speeds. By selectively allowing faster or slower molecules to pass through a gate, the demon appears to reduce entropy without expending energy. However, the act of gathering and processing information incurs a thermodynamic cost, ensuring that the overall entropy balance is maintained. This paradox underscores that information is a physical quantity with measurable effects on energy and entropy.

Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) Principle¶

Probability represents our incomplete information. Given partial knowledge about some variables how should we construct a probability distribution that is unbiased beyond what we know?

The Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) Principle provides the best approach: we choose probabilities to maximize Shannon entropy while satisfying given constraints.

This ensures the least biased probability distribution possible, consistent with the available information.

We seek to maximize subject to the constraints:

To enforce these constraints, we introduce Lagrange multipliers , leading to the Lagrangian (also called the objective function):

To maximize , we take its functional derivative with respect to :

Since is simply a constant normalization factor, we define and arrie at final expression for probability distribution:

Interperation of MaxEnt

The probability distribution takes an exponential form in the constrained variables .

The normalization constant (also called the partition function) ensures that the probabilities sum to 1.

The Lagrange multipliers encode the specific constraints imposed on the system.

This result is fundamental in statistical mechanics, where it leads to Boltzmann distributions, and in machine learning, where it underpins maximum entropy models.

Application MaxEnt: Biased Die Example¶

If we are given a fair die MaxENt would predict as there are no constraints.

But suppose we are given a biased die the average outcome of which is rolling on average a number . The entropy function to maximize becomes:

Solving the variational equation, we find that the optimal probability distribution follows an exponential form:

where is the partition function ensuring normalization:

To determine , we use the constraint :

This equation can be solved numerically for . In many cases, Newton’s method or other root-finding techniques can be employed to find the exact value of . This distribution resembles the Boltzmann factor in statistical mechanics, where higher outcomes are exponentially less probable.

Source

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import root

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = np.arange(1, 7)

target_mean = 4.2

def maxent_prob(lambdas):

lambda1 = lambdas[0]

Z = np.sum(np.exp(-lambda1 * x))

return np.exp(-lambda1 * x) / Z

def constraint(lambdas):

p = maxent_prob(lambdas)

mean = np.sum(x * p)

return [mean - target_mean]

# Solve for lambda

sol = root(constraint, [0.0])

lambda_opt = sol.x[0]

# Optimal distribution

p_opt = maxent_prob([lambda_opt])

print(f"λ1 = {lambda_opt:.4f}")

for i, p in enumerate(p_opt, 1):

print(f"P({i}) = {p:.4f}")

# Plot

plt.bar(x, p_opt, edgecolor='black')

plt.title("MaxEnt Distribution (Mean Constraint Only)")

plt.xlabel("Die Outcome")

plt.ylabel("Probability")

plt.xticks(x)

plt.grid(axis='y', linestyle='--', alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

λ1 = -0.2490

P(1) = 0.0818

P(2) = 0.1050

P(3) = 0.1347

P(4) = 0.1727

P(5) = 0.2216

P(6) = 0.2842

Relative Entropy¶

In the MaxEnt derivation, we implicitly maximized entropy relative to an underlying assumption of equal-probability microstates. We now make this idea precise.

Consider a 1D Brownian particle starting at and diffusing freely. Its probability distribution at time (t) is Gaussian:

The Shannon entropy of this distribution is

which evaluates to

suggesting that entropy grows as the particle spreads in space.

Problem: Grid Dependence of Shannon Entropy¶

For continuous variables, Shannon entropy is not absolute: it depends on the choice of spatial resolution (\Delta x). Refining the grid causes (S) to diverge, making it unsuitable for comparing entropy across different distributions or times.

To obtain a well-defined, resolution-independent measure, we instead use relative entropy.

Relative entropy quantifies the information cost of using when the system is actually distributed as . It is non-negative and vanishes if and only if .

Quantifying entropy of regions A and B

Let (X) be a random variable with distribution . Partition its domain into two disjoint regions (A) and (B).

Probabilities (weights)

Conditional (within-region) entropies would then be:

These quantify intrinsic spread / heterogeneity within each region, independent of how often the region is occupied.

Macro (between-region) entropy

Define a coarse-grained variable (M \in {A,B}).

This quantifies uncertainty about which region the system is in.

Exact entropy decomposition

$$ \boxed{ H(X) = H(M)

P_A H_A

P_B H_B } $$

Total entropy = between-region uncertainty + weighted within-region uncertainty.

: uncertainty between regions A and B

: uncertainty within regions (conditional entropies)

: weights that tell how much each region contributes

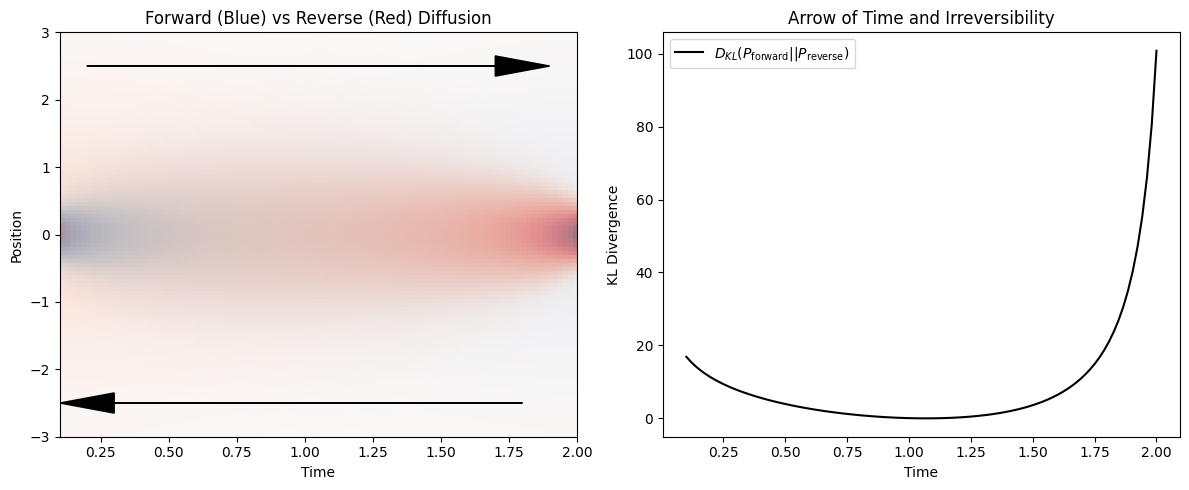

Asymmetry of KL Divergence and Irreversibility¶

Consider two normal distributions,

The KL divergence can be computed analytically:

$$ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(P|Q) = \ln\frac{\sigma_2}{\sigma_1}

\cdot \frac{\sigma_1^2+(\mu_1-\mu_2)^2}{2\sigma_2^2}

\frac{1}{2}. $$

This expression is not symmetric under , highlighting that KL divergence defines a directed notion of distance between distributions.

For diffusion, the probability distribution at time is Gaussian with variance . Comparing distributions at two times and yields:

This quantity is strictly positive unless (t_1=t_2).

Physical Interpretation of relative entropy¶

KL divergence measures the statistical distinguishability between probability distributions. For diffusion, the forward process (spreading in time) is statistically distinguishable from the hypothetical time-reversed process (spontaneous contraction).

This asymmetry reflects irreversibility: diffusion naturally increases entropy, while its time-reversed counterpart is overwhelmingly improbable.

This statistical asymmetry underlies the thermodynamic arrow of time.

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define time points

t_forward = np.linspace(0.1, 2, 100)

t_reverse = np.linspace(2, 0.1, 100)

# Define probability distributions for forward and reverse processes

x = np.linspace(-3, 3, 100)

sigma_forward = np.sqrt(t_forward[:, None]) # Diffusion spreads over time

sigma_reverse = np.sqrt(t_reverse[:, None]) # Reverse "contracts" over time

P_forward = np.exp(-x**2 / (2 * sigma_forward**2)) / (np.sqrt(2 * np.pi) * sigma_forward)

P_reverse = np.exp(-x**2 / (2 * sigma_reverse**2)) / (np.sqrt(2 * np.pi) * sigma_reverse)

# Compute Kullback-Leibler divergence D_KL(P_forward || P_reverse)

D_KL = np.sum(P_forward * np.log(P_forward / P_reverse), axis=1)

# Plot the distributions and KL divergence

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Plot forward and reverse distributions

ax[0].imshow(P_forward.T, extent=[t_forward.min(), t_forward.max(), x.min(), x.max()], aspect='auto', origin='lower', cmap='Blues', alpha=0.7, label='P_forward')

ax[0].imshow(P_reverse.T, extent=[t_reverse.min(), t_reverse.max(), x.min(), x.max()], aspect='auto', origin='lower', cmap='Reds', alpha=0.5, label='P_reverse')

ax[0].set_xlabel("Time")

ax[0].set_ylabel("Position")

ax[0].set_title("Forward (Blue) vs Reverse (Red) Diffusion")

ax[0].arrow(0.2, 2.5, 1.5, 0, head_width=0.3, head_length=0.2, fc='black', ec='black') # Forward arrow

ax[0].arrow(1.8, -2.5, -1.5, 0, head_width=0.3, head_length=0.2, fc='black', ec='black') # Reverse arrow

# Plot KL divergence over time

ax[1].plot(t_forward, D_KL, label=r'$D_{KL}(P_{\mathrm{forward}} || P_{\mathrm{reverse}})$', color='black')

ax[1].set_xlabel("Time")

ax[1].set_ylabel("KL Divergence")

ax[1].set_title("Arrow of Time and Irreversibility")

ax[1].legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Relative Entropy in Machine Learning¶

If assigns very low probability where is large, the term becomes large, strongly penalizing underestimation of the data distribution.

If is broader than and assigns probability to unlikely regions, the penalty is mild because is small there.

As a result, KL divergence is asymmetric and not a true distance metric.

It penalizes missing probability mass far more than wasting probability mass, which is why it is widely used in machine learning and statistical inference.

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact

from scipy.stats import norm

def plot_gaussians(mu1=0, sigma1=1, mu2=1, sigma2=2):

x_values = np.linspace(-5, 5, 1000) # Define spatial grid

P = norm.pdf(x_values, loc=mu1, scale=sigma1) # First Gaussian

Q = norm.pdf(x_values, loc=mu2, scale=sigma2) # Second Gaussian

# Avoid division by zero in KL computation

mask = (P > 0) & (Q > 0)

D_KL_PQ = np.trapezoid(P[mask] * np.log(P[mask] / Q[mask]), x_values[mask]) # D_KL(P || Q)

D_KL_QP = np.trapezoid(Q[mask] * np.log(Q[mask] / P[mask]), x_values[mask]) # D_KL(Q || P)

# Plot the distributions

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

plt.plot(x_values, P, label=fr'$P(x) \sim \mathcal{{N}}({mu1},{sigma1**2})$', linewidth=2)

plt.plot(x_values, Q, label=fr'$Q(x) \sim \mathcal{{N}}({mu2},{sigma2**2})$', linewidth=2, linestyle='dashed')

plt.fill_between(x_values, P, Q, color='gray', alpha=0.3, label=r'Difference between $P$ and $Q$')

# Annotate KL divergences

plt.text(-4, 0.15, rf'$D_{{KL}}(P || Q) = {D_KL_PQ:.3f}$', fontsize=12, color='blue')

plt.text(-4, 0.12, rf'$D_{{KL}}(Q || P) = {D_KL_QP:.3f}$', fontsize=12, color='red')

# Labels and legend

plt.xlabel('$x$', fontsize=14)

plt.ylabel('Probability Density', fontsize=14)

plt.title('Interactive KL Divergence Between Two Gaussians', fontsize=14)

plt.legend(fontsize=12)

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

interact(plot_gaussians,

mu1=widgets.FloatSlider(min=-3, max=3, step=0.1, value=0, description='μ1'),

sigma1=widgets.FloatSlider(min=0.1, max=3, step=0.1, value=1, description='σ1'),

mu2=widgets.FloatSlider(min=-3, max=3, step=0.1, value=1, description='μ2'),

sigma2=widgets.FloatSlider(min=0.1, max=3, step=0.1, value=2, description='σ2'))

<function __main__.plot_gaussians(mu1=0, sigma1=1, mu2=1, sigma2=2)>Protein Sequences, Evolution, and Entropy

1. Sequence Conservation as Low Entropy

Protein sequences evolve under functional and structural constraints. At each sequence position (i), amino-acid usage is described by a probability distribution (p_i(a)).

The site entropy

measures variability at that position.

Low entropy → strong evolutionary conservation (few amino acids tolerated)

High entropy → weak constraint (many amino acids allowed)

Conserved sites often correspond to active sites, binding interfaces, or structural cores.

2. Coevolution as Shared Constraint

Some positions are not conserved individually but are correlated across evolution.

For two positions , define a joint distribution . Their mutual information

quantifies coevolution.

High : mutations at depend on mutations at

Indicates structural contacts, compensatory mutations, or allosteric coupling

Coevolution reflects constraints on combinations, not individual residues.

3. Entropy Reduction by Function

Evolution does not minimize entropy everywhere—it redistributes it.

Functional requirements reduce entropy at critical sites

Flexibility and robustness allow entropy elsewhere

Coevolution preserves function while permitting sequence diversity

Thus, proteins balance:

4. Big Picture¶

Entropy quantifies how many sequences are compatible with function

Conservation identifies where entropy is suppressed

Coevolution reveals how entropy is shared across positions

Evolution sculpts protein sequences by concentrating entropy away from functionally critical degrees of freedom.

Problems¶

Problem-1: Compute Entropy for gas partitioning¶

A container is divided into two equal halves. It contains 100 non-interacting gas particles that can freely move between the two sides. A macrostate is defined by the fraction of particles in the right half .

Write down an exprssion for entropy S(f)

Consult the section on Random Walk and Combinatorics formula

Evaluate for:

(10% left, 90% right)

(25% left, 75% right)

(50% left, 50% right)

Relate entropy to probability using Large Deviation Theory and answer the following questions:

Which macrostate is most probable?

How does entropy influence probability?

Why are extreme fluctuations (e.g., ) unlikely?

Problem-2: Guassians in 2D¶

Below we generate three 2D gaussians with varying degree of correltion betwene and . Run the code to visualize

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define mean values

mu_x, mu_y = 0, 0 # Mean of x and y

# Define standard deviations

sigma_x, sigma_y = 1, 1 # Standard deviation of x and y

# Define different correlation coefficients

correlations = [0.0, 0.5, 0.9] # Varying degrees of correlation

# Generate and plot 2D Gaussian samples for different correlations

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(15, 5))

for i, rho in enumerate(correlations):

# Construct covariance matrix

covariance_matrix = np.array([[sigma_x**2, rho * sigma_x * sigma_y],

[rho * sigma_x * sigma_y, sigma_y**2]])

# Generate samples from the 2D Gaussian distribution

samples = np.random.multivariate_normal([mu_x, mu_y], covariance_matrix, size=1000)

# Plot scatter of samples

axes[i].scatter(samples[:, 0], samples[:, 1], alpha=0.5)

axes[i].set_title(f"2D Gaussian with Correlation ρ = {rho}")

axes[i].set_xlabel("X")

axes[i].set_ylabel("Y")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Compute entropy using probability distributions and

Compute relative entropy which is known as Mutual Information. How can you interpret this quantity

You will need these functions. Also check out

scipy.stats.entropy

| Task | numpy Function |

|---|---|

| Compute histogram for | numpy.histogram2d |

| Compute histogram for , | numpy.histogram |

| Normalize histograms to get probabilities | numpy.sum() |

| Compute entropy manually | numpy.log(), numpy.sum() |

Problem-3: Gambling with ten sided die¶

Take a ten sided die described by random variable

Experiment shows that after many throughs the average number die shows is with variance .

Determine probabilities of ten die sides . You can use the code for six sided die in this notebook. But remember there are now two constraints one on mean and one on variance!

Problem-3 Biased Random walker in 2D¶

A random walker moves on a 2D grid, taking steps in one of four possible directions:

Each step occurs with unknown probabilities:

which satisfy the normalization condition:

Experimental measurements indicate the expected displacement per step:

Using the Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) principle, determine the probabilities by numerically solving an optimization problem.

You will need

scipy.minimize(entropy, initial_guess, bounds=bounds, constraints=constraints, method='SLSQP')to do the minimization. Check the documentation to see how it works

Problem-5: Arrow of time in 2D diffusion¶

Simulate 2D diffusion using a Gaussian distribution

Model diffusion in two dimensions with a probability distribution:

Generate samples at different time steps using

numpy.random.normalwith time-dependent variance.

Compute the relative entropy as a function of time

Use relative entropy (Kullback-Leibler divergence) to compare the probability distributions at time with a reference time :

Compare forward and reverse evolution of diffusion

Compute the relative entropy between forward () and reverse () diffusion distributions.

Quantify how diffusion leads to irreversible evolution by evaluating:

Interpret the results

How does relative entropy change with time?

Why is the forward process distinguishable from the reverse process?

What does this tell us about the arrow of time?