Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE)¶

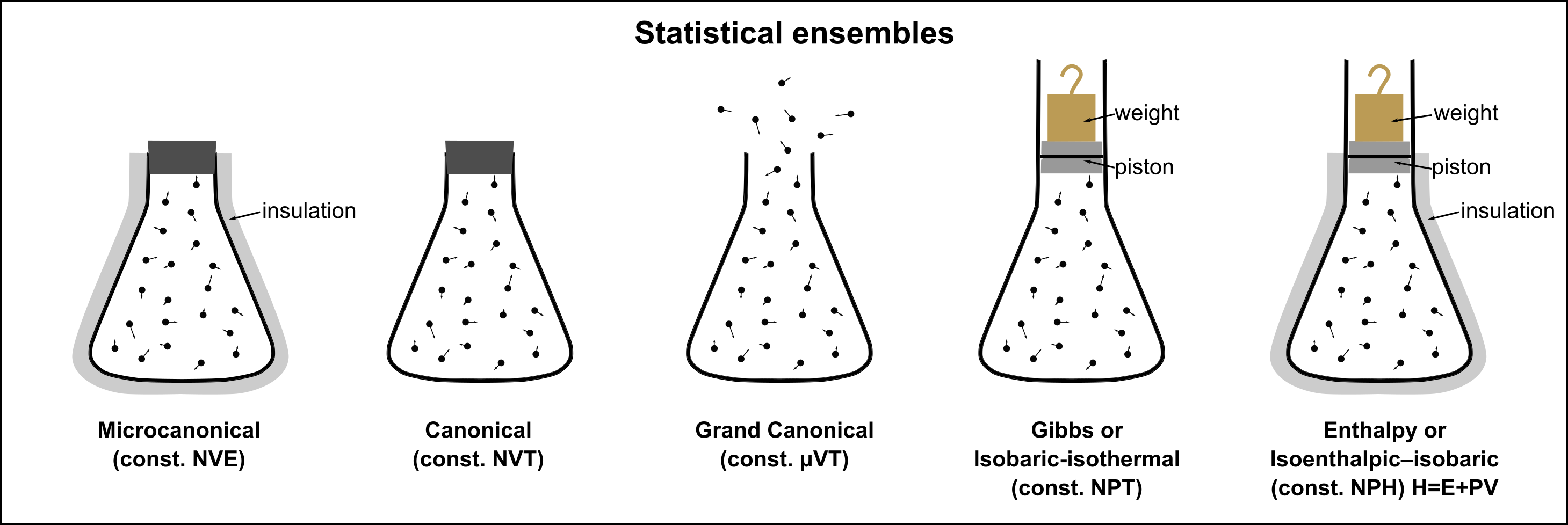

A collection of all possible microscopic arrangements consistent with an equilibrium thermodynamic state is called statistical ensemble.

Ensemble defines sample space over microstates over which we define micro and macro-state probabilities

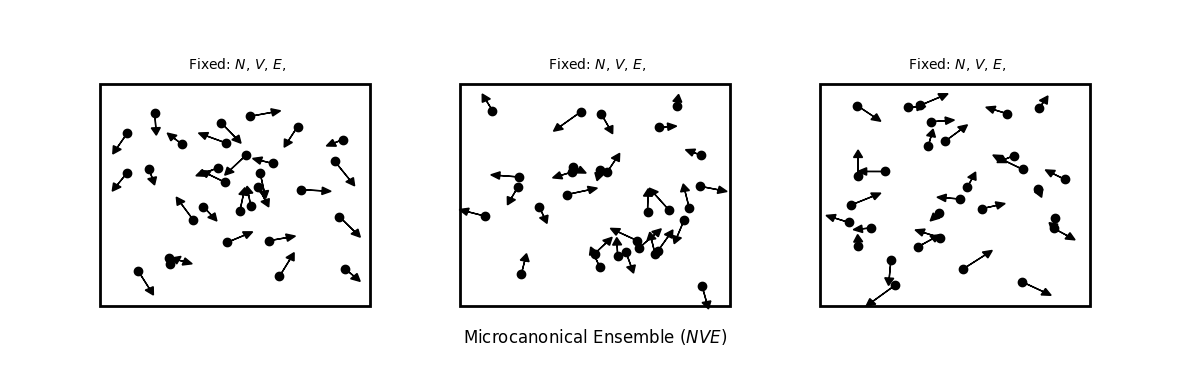

Consider an isolated fluid system with , and . This is called a microcanonical ensemble

In the absence of any physical constraints, no micro state is more probable than any other. This is known as “principle of equal a priory probability”.

We can use postulate of equal microstate probabilities and plug into probabilisti expression of entropy to obtain a simple relationship between number of microstates and entropy:

Simple example of NVE ensemble

Consider a system of three non-interacting spins, each of which can point either up () or down (), and both orientations carry the same energy . The total energy is therefore always , and the microcanonical ensemble is defined by , , and .

Because every spin state costs the same energy, all configurations are microstates of this ensemble:

There are microstates, and the Boltzmann entropy is:

For spins with equal energies, and entropy scales linearly (extensively) with system size :

Microcanonical partition function grows exponentially with system size¶

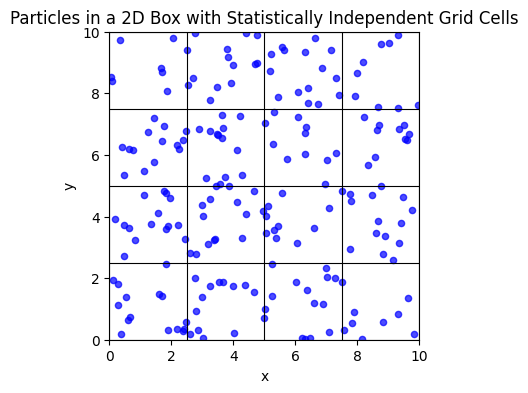

To estimate how the number of microstates behave as a function of system size consider particles in a volume , and particle density

Dividing the system into statistically independent subregions (each of volume ) containing microstates each, we get:

We find that number of microstates grows exponentially with system size . This implies a large deviation property: entropy scales extensively and grows monotonically with energy.

Applications of NVE¶

Particles in a box¶

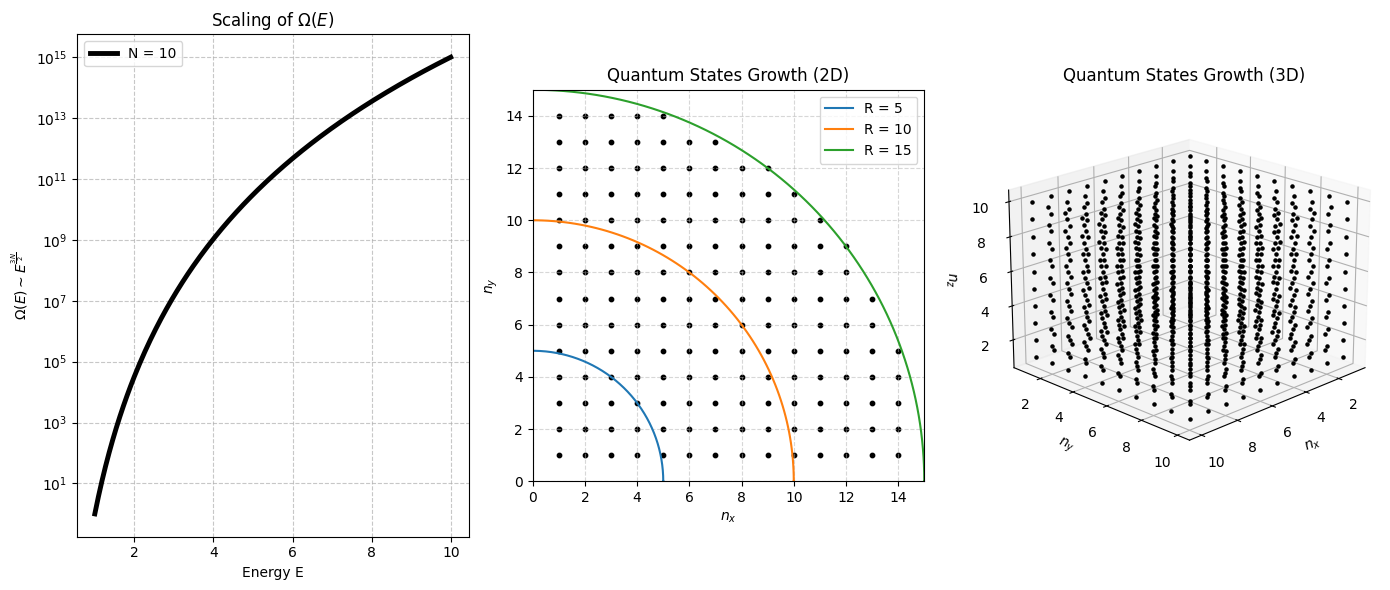

For a single quantum particle in a cubical box of side , the allowed energy levels are:

Where are positive integers (quantum numbers).

To determine the number of microstates with total energy at most , we count the number of allowed quantum states satisfying:

For large , this corresponds to counting integer lattice points inside a sphere of radius:

Since the number of points inside a sphere scales approximately as the volume of the sphere, we get:

Thus, for a single particle, the number of accessible microstates grows as:

For independent particles, each particle contributes an independent set of quantum numbers, meaning we now count lattice points in a -dimensional hypersphere.

Source

# Create a combined figure

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 6))

# ---------------- Plot 1: Scaling of Microstates ----------------

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(131)

E = np.linspace(1, 10, 200)

N=10

Omega = E**(1.5 * N)

ax1.plot(E, Omega, label=f"N = {N}", color='black', lw=3.5)

ax1.set_xlabel("Energy E")

ax1.set_ylabel(r"$\Omega(E) \sim E^{\frac{3N}{2}}$")

ax1.set_title("Scaling of $\Omega(E)$")

ax1.set_yscale('log') # Logarithmic scale to better display the exponential growth

ax1.grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

ax1.legend()

# ---------------- Plot 2: Growth of Quantum States in 2D ----------------

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(132)

n_max = 15 # Reduce max quantum number for clarity

R_values = [5, 10, 15]

n_x_values = np.arange(1, n_max + 1)

n_y_values = np.arange(1, n_max + 1)

for n_x in n_x_values:

for n_y in n_y_values:

energy = n_x**2 + n_y**2

if energy <= max(R_values)**2:

ax2.scatter(n_x, n_y, color='black', s=10)

theta = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 300)

for R in R_values:

ax2.plot(R * np.cos(theta), R * np.sin(theta), label=f'R = {R}', linewidth=1.5)

ax2.set_xlabel(r'$n_x$')

ax2.set_ylabel(r'$n_y$')

ax2.set_title('Quantum States Growth (2D)')

ax2.legend()

ax2.set_xlim(0, n_max)

ax2.set_ylim(0, n_max)

ax2.grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.5)

ax2.set_aspect('equal')

# ---------------- Plot 3: 3D Representation of Quantum States ----------------

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(133, projection='3d')

n_max_3d = 10 # Reduce quantum number range for clarity

# Generate 3D quantum states

n_z_values = np.arange(1, n_max_3d + 1)

for n_x in np.arange(1, n_max_3d + 1):

for n_y in np.arange(1, n_max_3d + 1):

for n_z in np.arange(1, n_max_3d + 1):

energy = n_x**2 + n_y**2 + n_z**2

if energy <= max(R_values)**2:

ax3.scatter(n_x, n_y, n_z, color='black', s=5)

ax3.set_xlabel(r'$n_x$')

ax3.set_ylabel(r'$n_y$')

ax3.set_zlabel(r'$n_z$')

ax3.set_title('Quantum States Growth (3D)')

ax3.view_init(elev=20, azim=45)

# Show the combined figure

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

<>:15: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\O'

<>:15: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\O'

/tmp/ipykernel_2926/3458926410.py:15: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\O'

ax1.set_title("Scaling of $\Omega(E)$")

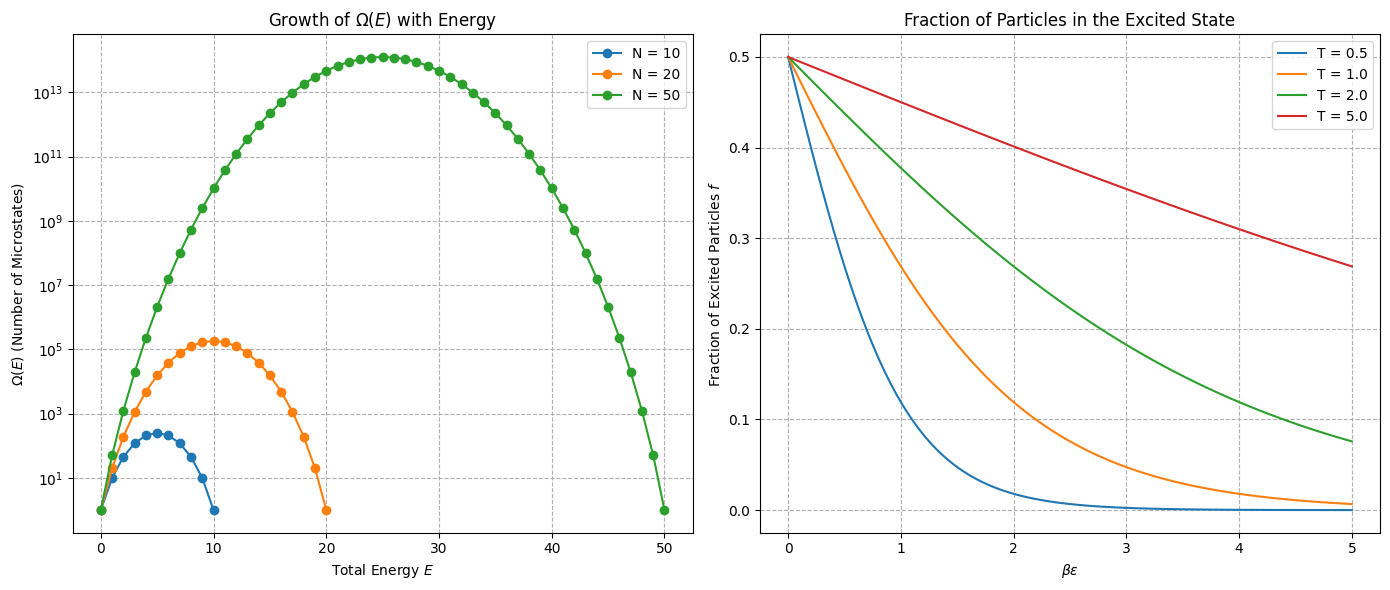

Two state system¶

Given non-interacting spins where each spin can be up () with energy or down () with energy . The total energy is:

Determine fraction of excited states where is number of up spins. Show how this fraction changes with temperature

Using Striling’s approximation we get:

We connect number of excited states to equilibrium temperature via thermodynamics

This is the well-known Boltzmann factor result for a two-level system in thermal equilibrium. At high temperatures (), approximately half the spins are excited (). At low temperatures (), the excited fraction vanishes exponentially: .

Source

import numpy as np

import scipy.special as sp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create a figure with two subplots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 6))

# Subplot 1: Growth of Ω(E) with Energy for Different Spin System Sizes

N_values = [10, 20, 50] # Different spin system sizes

for N in N_values:

energies = np.arange(0, N+1, 1) # Possible energy levels

multiplicities = sp.binom(N, energies) # Compute binomial coefficient

axes[0].plot(energies, multiplicities, label=f'N = {N}', linestyle='-', marker='o')

# Plot settings for first subplot

axes[0].set_yscale('log') # Use logarithmic scale to highlight exponential growth

axes[0].set_xlabel(r'Total Energy $E$')

axes[0].set_ylabel(r'$\Omega(E)$ (Number of Microstates)')

axes[0].set_title(r'Growth of $\Omega(E)$ with Energy')

axes[0].legend()

axes[0].grid(True, which='both', linestyle='--')

# Subplot 2: Fraction of Particles in the Excited State vs. Temperature

epsilon = 1.0 # Set energy scale to 1 for simplicity

k_B = 1.0 # Boltzmann constant set to 1 for simplicity

T_values = [0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0] # Different temperature values

# Define function for fraction of excited particles

def fraction_excited(beta_epsilon):

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(beta_epsilon))

# Generate beta_epsilon values

beta_epsilon_values = np.linspace(0, 5, 100)

# Plot f for different temperatures

for T in T_values:

beta_epsilon = epsilon / (k_B * T) * beta_epsilon_values

f_values = fraction_excited(beta_epsilon)

axes[1].plot(beta_epsilon_values, f_values, label=f"T = {T}")

# Plot settings for second subplot

axes[1].set_xlabel(r"$\beta \epsilon$")

axes[1].set_ylabel(r"Fraction of Excited Particles $f$")

axes[1].set_title("Fraction of Particles in the Excited State")

axes[1].legend()

axes[1].grid(True, linestyle='--')

# Adjust layout

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

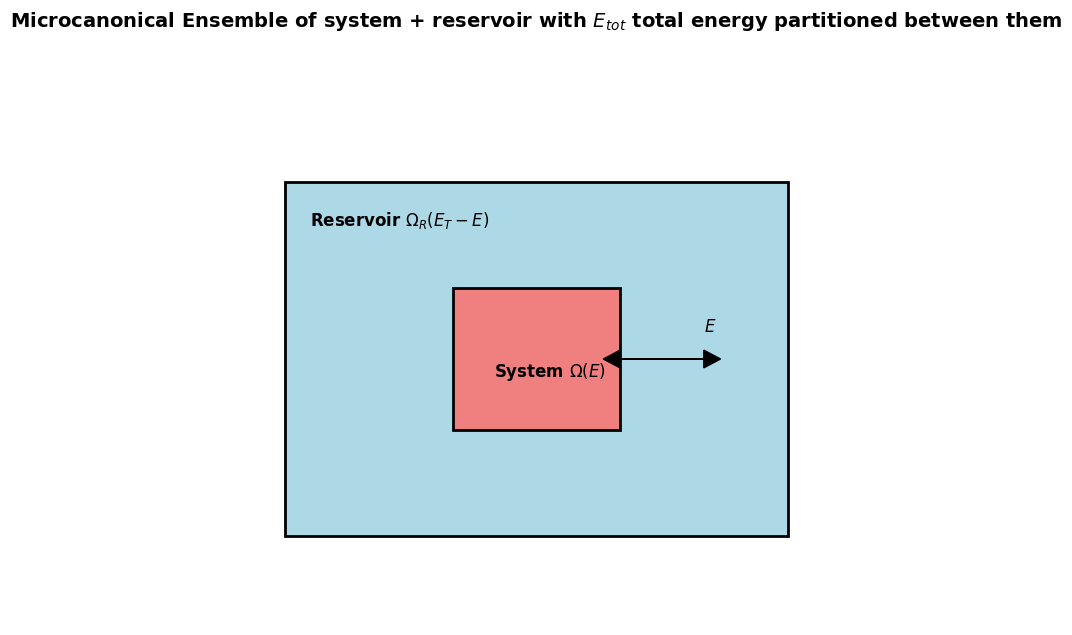

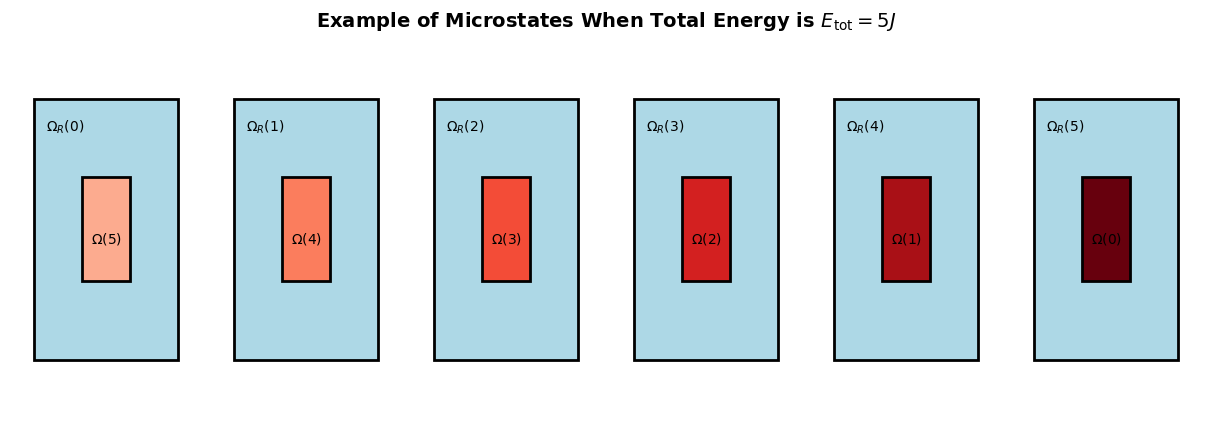

Energy partitioning in an isolated system¶

is the total number of microstates of the whole isoluate box divided into:

number of microstates available to the system of interest

number of microstates available to the Reservoir

Since reservoir and system can be considered statistically independent, the probability of finding the system in a macrostate with energy is:

This is a ratio of all microstate where system gets and reservoir energies divided by total number of microstates. The latter given as sum of all possible partitionings of energy

We can see that probability of macrostates is normalized . The system is more likely to be in a macrostate if there are more microstates that reaalize this partitioning.

Source

# Re-import necessary libraries since execution state was reset

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define different system sizes

system_sizes = [(5, 10), (10, 20), (20, 40)]

# Define total energy

E_total = 5

# Create figure

plt.figure(figsize=(7, 6))

# Loop over different system sizes and plot

for N1, N2 in system_sizes:

# Define energy range for system 1 (from 0 to E_total)

E1_values = np.linspace(0.01, E_total, 50) # Avoid E=0 to prevent singularities

E2_values = E_total - E1_values # Energy remaining for system 2

# Compute microstates using Omega(E) ~ E^(3N/2)

Omega1 = E1_values**(3 * N1 / 2)

Omega2 = E2_values**(3 * N2 / 2)

# Compute total number of microstates (product of subsystems)

Omega_total = Omega1 * Omega2 / np.sum(Omega1 * Omega2) # Normalize to get probability

# Plot results

plt.plot(E1_values, Omega_total, label=rf'$N_1={N1}, N_2={N2}$')

# Draw vertical line at the peak (mean energy E = U)

E_peak = E1_values[np.argmax(Omega_total)]

plt.axvline(E_peak, color='black', linestyle=':', linewidth=2)

# Plot settings

plt.xlabel(r"Energy given to System: $E_1$")

plt.ylabel(r"$P(E_1)$")

plt.title("Probability Distribution of Energy Partitioning")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

# Show plot

plt.show()

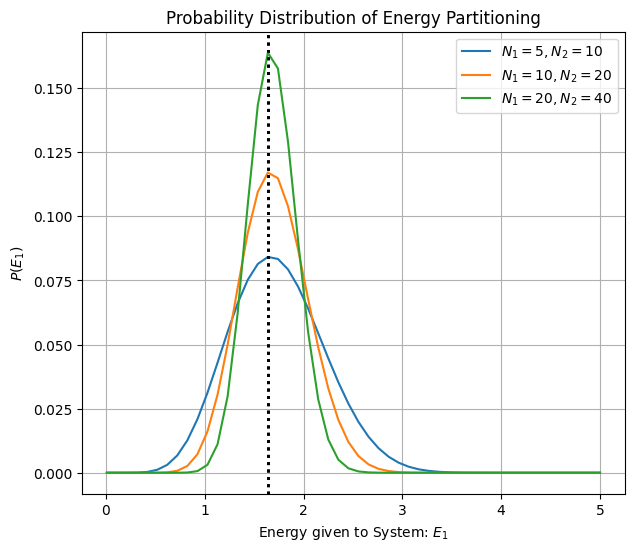

Temperature is the driver of energy partitioning¶

Which partitioning is most likely? For two systems exchanging energy we can write down probability of macrostate and find its maxima with respect to

Since we note that Maximizing probability of a macrostate is the same as maximizing entropy of macrostate!

We also come to appreciate that inverse temperature , quantifies rate of growth of microstates.

At lower temperatures is larger indicating faster growth of microstates. At higher temperatures is smaller indicating slower groth of microstates with addition of energy.

Thermal Equilibrium in Ideal Gases¶

For a system of non-interacting particles in a box, the number of microstates follows . The entropy is defined as:

Maximizing entropy with respect to energy exchange between two subsystems gives use the equilibrium value that system gets.

Plugging the definition of temperature on left hand side which in equilibrium we see is equal for two systems exchangeing energy:

This leads to the well-known result that each degree of freedom receives of thermal energy:

Solving for we also see that each system gets energy proportionate to its size

Why are Energy Fluctuations are Gaussian

To analyze small fluctuations , we expand the total entropy around in a Taylor series:

Since the first dderivative vanishes at equilibrium, the dominant term governing the probability is the second dderivative:

Here, we use the equilibrium conditions where and denote the average internal energies of subsystems 1 and 2.

The negative sign confirms that entropy is maximized at equilibrium, ensuring that small deviations follow:

The variance of energy fluctuations follows from the curvature of entropy:

In the thermodynamic limit, where , this scales as:

Thus, energy fluctuations around equilibrium follow a Gaussian distribution, with variance scaling as . This implies that fluctuations relative to the mean become negligible in the thermodynamic limit, reinforcing the stability of equilibrium.

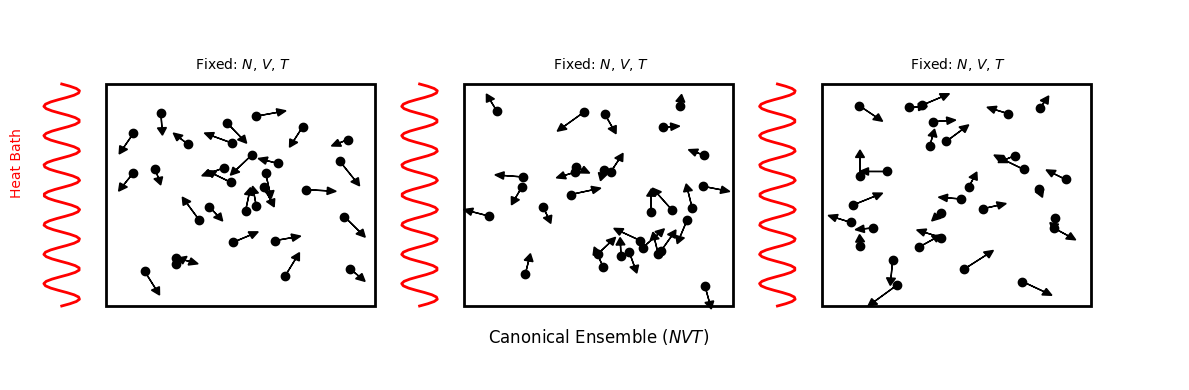

Constant temperature ensemble (NVT)¶

We start by considering an isolated box ( ensemble) inside which there is a system of interest which is exchanging energy with much larger reservoir or heat bath.

Using the fact that reservoir is much larger than the system we can taylor expand log of microstates (entropy) around

The first factor is a constant independent of energy the second factor in front of energy is recognize as inverse temperature

We have now have an ensemble of microstates of systems specified by variables and and reservoir influence enters through temperature!

Ensemble of microstates has different energies that are exponentially distributed (price for borrowing energy from the bath).

MaxEnt leads to canonical distribution

We can use Maximizing Entropy principle to assing probabilities for an esnemble where we have a physical constraint placed on having fixed average energy

Probability of each microstate is now weighted by an exponential of microstate Energies:

Probability of each macrostate containing number of microstates would be:

By comparing with thermodynamics we can confirm that lagrange coefficinet is inverse temperature

Partition Functions and Thermodynamic limit¶

We find that microcanonical and canonical ensebles are linked via Laplace transform. Recall that and free energy via Legendre transform

This shows that when going from to ensemble we are adopting a conveneint variable by replacing .

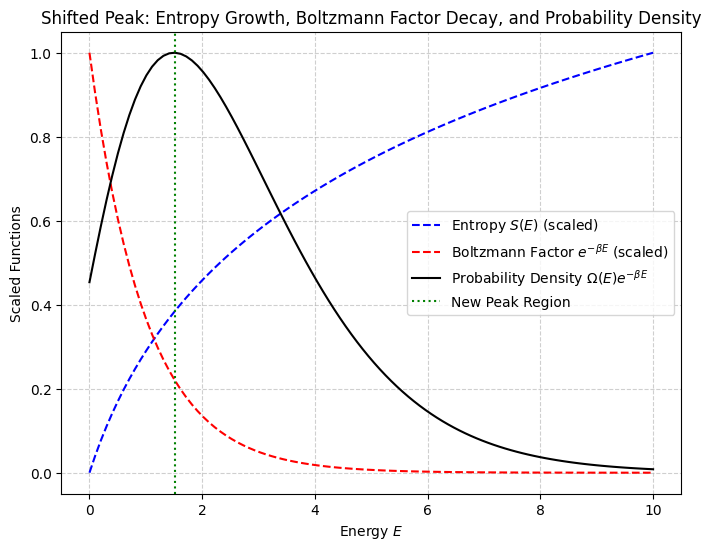

The number of states grows exponentially with system size , while the Boltzmann factor decays exponentially with energy

The dominant contribution to the partition function comes from narrow region around ensemble average or equilibrium value of energy . Deviations from average are xponentially negligble!

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define energy range

E = np.linspace(0, 10, 100)

# Define parameters

beta = 1.0 # Inverse temperature (1/kT)

# Compute the Boltzmann factor

Boltzmann_factor = np.exp(-beta * E)

# Increase the entropy prefactor to shift the peak to the right

S_prefactor_new = 2.5 # Larger prefactor makes entropy increase faster

# Recalculate entropy and probability density

S_new = S_prefactor_new * np.log(1 + E)

Probability_density_new = np.exp(S_new) * Boltzmann_factor

# Create the updated plot

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

# Plot entropy (scaled for visualization)

plt.plot(E, S_new / max(S_new), label=r"Entropy $S(E)$ (scaled)", color="blue", linestyle="--")

# Plot Boltzmann factor (scaled for visualization)

plt.plot(E, Boltzmann_factor / max(Boltzmann_factor), label=r"Boltzmann Factor $e^{-\beta E}$ (scaled)", color="red", linestyle="--")

# Plot updated probability density (product of both)

plt.plot(E, Probability_density_new / max(Probability_density_new), label=r"Probability Density $\Omega(E) e^{-\beta E}$", color="black")

# Highlight new peak region

E_peak_new = E[np.argmax(Probability_density_new)]

plt.axvline(E_peak_new, color="green", linestyle=":", label="New Peak Region")

# Labels and title

plt.xlabel("Energy $E$")

plt.ylabel("Scaled Functions")

plt.title("Shifted Peak: Entropy Growth, Boltzmann Factor Decay, and Probability Density")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, linestyle="--", alpha=0.6)

# Show plot

plt.show()

Examples of using NVT¶

non-interacting spins¶

Consider an ensemble of three non-interacting spins under constant temperature. The up spin has and down spin 0 energy.

| Microstate | Configuration | Total Energy | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 3 | ||

| 5 | 3 | ||

| 6 | 3 | ||

| 7 | 3 | ||

| 8 | 1 |

The partition function would be sum over all microstaes.

Probability of a microstate is:

Probability of a macrostate is

Two-state particles (NVT)¶

Consider a simple two-level system where lower level has energy 0 and upper level . Determine how the fraction of excited states changes with temperature.

Solving a two-state particle system in an NVT ensemble is much easier because the partition function decouples into single particle contributions.

We obtained same expression we got when using NVE but it tooks us less number of steps!

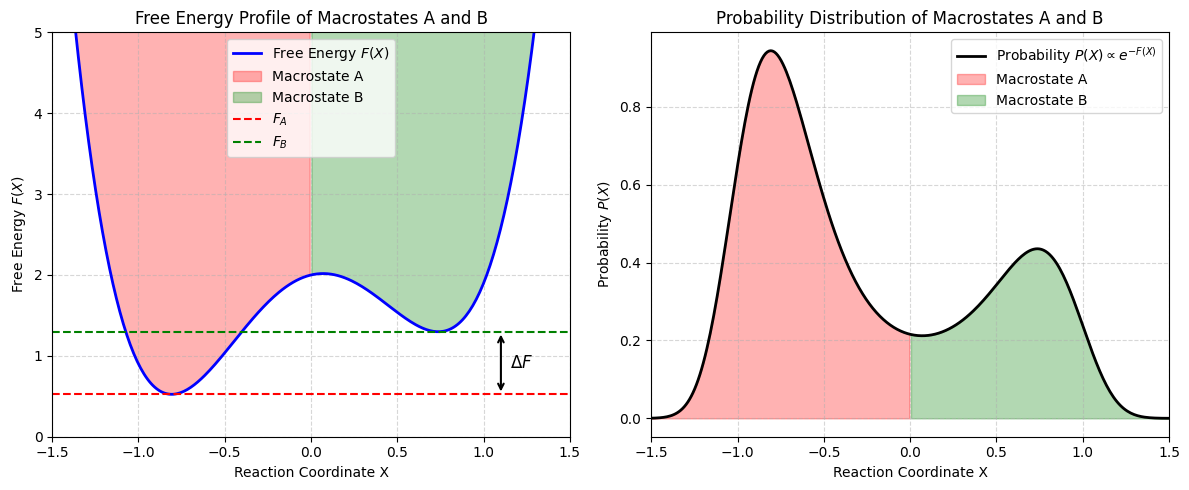

Free energy and macrostate probabilities¶

Microstates: The relative population of microstates is dictated by the ratio of Boltzmann weights which depends on energy difference

Macrostates: Probability of macrostates with energy is obtained by summing over all microstates with energy E_A or simply by multiplying by . The latter is related to entropy, which ends up turning the numerator into the free energy of a macrostate :

The relative population of macrostates is dictated by the ratio of entropic term times Boltzmann weights which depends on free energy difference

Source

# Define reaction coordinate

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = np.linspace(-2, 2, 400)

# Define a tilted asymmetric double-well free energy profile

F_x = 3 * (x**4 - 1.2*x**2) + 2 + 0.5*x # Added tilt to shift one minimum

# Identify macrostates A and B based on regions left and right of the transition state (x=0)

x_A_region = x[x < 0] # Left basin (macrostate A)

x_B_region = x[x > 0] # Right basin (macrostate B)

F_A = np.min(F_x[x < 0]) # Free energy of macrostate A (left well minimum)

F_B = np.min(F_x[x > 0]) # Free energy of macrostate B (right well minimum)

ΔF = F_B - F_A # Free energy difference

# Compute probability distribution P(X) from free energy F(X)

P_x = np.exp(-F_x) # Exponential of negative free energy

P_x /= np.trapezoid(P_x, x) # Normalize probability

# Create figure with side-by-side subplots: Free Energy and Probability Distribution

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5), sharex=True)

# --- Free Energy Profile ---

axes[0].plot(x, F_x, label=r'Free Energy $F(X)$', color='b', linewidth=2)

axes[0].fill_between(x_A_region, F_x[x < 0], max(F_x), color='red', alpha=0.3, label="Macrostate A")

axes[0].fill_between(x_B_region, F_x[x > 0], max(F_x), color='green', alpha=0.3, label="Macrostate B")

axes[0].axhline(F_A, color='red', linestyle='--', label=r'$F_A$')

axes[0].axhline(F_B, color='green', linestyle='--', label=r'$F_B$')

# Indicate ΔF with an arrow

axes[0].annotate("", xy=(1.1, F_B), xytext=(1.1, F_A),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="<->", color='black', linewidth=1.5))

axes[0].text(1.15, (F_A + F_B) / 2, r'$\Delta F$', va='center', fontsize=12, color='black')

axes[0].set_xlabel("Reaction Coordinate X")

axes[0].set_ylabel("Free Energy $F(X)$")

axes[0].set_title("Free Energy Profile of Macrostates A and B")

axes[0].legend()

axes[0].grid(True, linestyle="--", alpha=0.5)

axes[0].set_xlim([-1.5, 1.5])

axes[0].set_ylim([0, 5])

# --- Probability Distribution ---

axes[1].plot(x, P_x, label=r'Probability $P(X) \propto e^{-F(X)}$', color='black', linewidth=2)

axes[1].fill_between(x_A_region, P_x[x < 0], 0, color='red', alpha=0.3, label="Macrostate A")

axes[1].fill_between(x_B_region, P_x[x > 0], 0, color='green', alpha=0.3, label="Macrostate B")

axes[1].set_xlabel("Reaction Coordinate X")

axes[1].set_ylabel("Probability $P(X)$")

axes[1].set_title("Probability Distribution of Macrostates A and B")

axes[1].legend()

axes[1].grid(True, linestyle="--", alpha=0.5)

# Adjust layout and show the plots

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Energy Fluctuations¶

Log of canonical partition function has some interesting mathematical properties.

We are going to show that first and second dderivatives yield average and fluctuations of energy.

The ensemble average energy can be related to the dderivative of log of partition function:

To quantify fluctuations, we define the variance of energy and proceed to show that this is equal to second derivative of logZ

Taking first dderivative:

Taking the second dderivative:

Since , we can use chain rule and express this in terms of temperature:

Where in the last line we used definition of heat capacity

The probability distribution of energy, , follows a Gaussian distribution in equilibrium:

Relative energy fluctuations decrease with . In the thermodynamic limit , fluctuations become negligible, justifying ensemble equivalence.

Statistical nature of irreversibility¶

From the perspective of the NVE ensemble, we can state that if the number of accessible microstates increases upon the removal of a constraint, then reinstating the constraint will not spontaneously reduce it. This reflects the fundamental irreversibility of spontaneous processes in an isolated system:

A similar conclusion holds in the NVT ensemble: Under constant temperature, the number of microstates, represented by the partition function , increases during a spontaneous process when a system is in contact with a heat bath.

This formulation underscores the irreversibility of thermodynamic processes and highlights the natural tendency of a system to evolve towards configurations with higher entropy (in the microcanonical ensemble) or lower free energy (in the canonical ensemble).

Problems¶

Problem 1 Shottky defects¶

Schotky defects are vacancies in a lattice of atoms. Creating a single vacancy costs an energy . Consider a lattice with atoms and vacacnies. In this model the total energy is solely a function of defects:

Write down number of states and compute the entropy via Boltzmann formula. Plot number of states as a function of energy. You can use log of number of states for plotting.

Compute how the temperature would affect the fraction of vacancies on the lattice. Plot fraction of vacancies as a function of temperature.

How would the total energy depend on temperature . Derive expression for the high temperature limit ().

Plot total energy as a function of temperature E(T)

Problem 2 Lattice gas¶

Consider particles distributed among cells (with ). This is a lattice model of a dilute gas. Suppose that each cell may be either empty or occupied by a single particle. The number of microscopic states of this syste will be given by:

Obtain an expression for the entropy per particle where .

From this simple fundamental equation, obtain an expression of equation of state .

Write an expansion of in terms of density . Show that the first term gives Boyle law of ideal gases.

Sketch a graph of , where is a chemical potential as a function of density. Comment on and limits.

Problem 3 Polymer Elasticity¶

Solve the problem 2.7 from the book.

Problem 4¶

Consider a system of N classical and non-interacting particles in contact with a thermal reservoir at a temperature . Each particle can have be in three states with energy 0, or where .

Obtain an expression for then compute the average and fluctuation of energy.

Plot the heat capacity as a function of temperature

Plot the average enegy as a function of temperature

Plot the entropy as a function of temperature .

Problem 5¶

Consider lattice sites which have quantum spins (not to be confused with entropy) with a mangnetic moment . Spins are subject to a uniform magnetic field in z direction making the energy of each spin where is the magnetic quantum number thattakes on three possible values .

Compute the entropy and the magnetization of the system

Plot entropy as a function of temperatures and study the limit of low temperatures