Quantization of Phase Space in Units of ¶

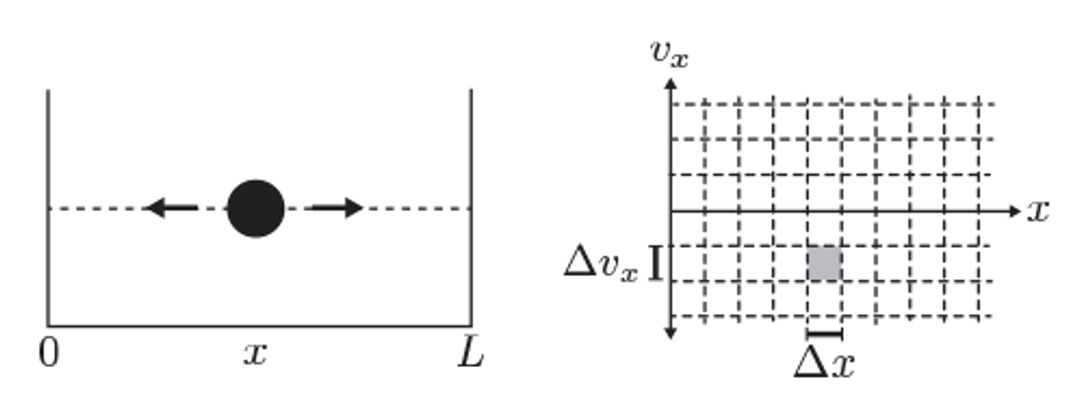

Illustration of phase space for a 1D particle in a box.

In classical mechanics, a system’s state is represented as a point in phase space, with coordinates for each degree of freedom. The number of microstates is, in principle, infinite because both position and momentum can vary continuously.

However, in quantum mechanics, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle imposes a fundamental limit on how precisely position and momentum can be specified:

This implies that we cannot resolve phase space with arbitrary precision. Instead, each distinguishable quantum state occupies a minimum phase space volume on the order of:

For a system with degrees of freedom (e.g for particles in three dimensions), the smallest resolvable cell in phase space has volume:

To compute the number of accessible microstates in a given region of phase space, we divide the classical phase space volume by the smallest quantum volume

Since N particles are indistingusihable and classical mechanics has no such concept we have to manually divide numer of microstates by

An explicit expression for number of microstates for a given energy is written by using delta function which counts all microstates in phase-space where

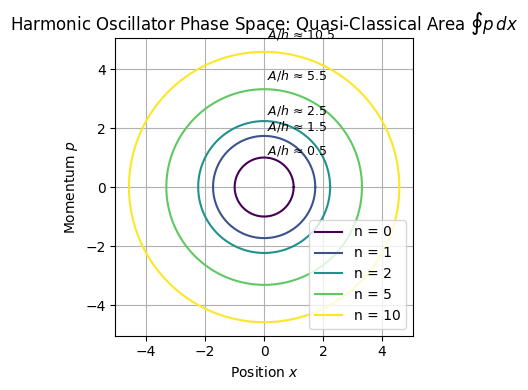

Phase-space of a harmonic oscillator

= position, = momentum, = mass, = angular frequency

This Hamiltonian gives the total energy of a particle undergoing simple harmonic motion.

Setting , we get the constant-energy curve:

This is the equation of an ellipse in the phase space, with:

Semi-major axis: (in )

Semi-minor axis: (in )

Compute Area of the Ellipse (Classical Action)

Plugging in quantum mechanical expression of quantized energies of harmonic oscillator

This area corresponds to the classical action integral , which in semiclassical quantization becomes:

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Set constants

hbar = 1.0

h = 2 * np.pi * hbar

m = 1.0

omega = 1.0

# Quantum numbers to plot

n_values = [0, 1, 2, 5, 10]

# Prepare plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 4))

# Colors for each energy level

colors = plt.cm.viridis(np.linspace(0, 1, len(n_values)))

# Store areas for demonstration

areas = []

# Plot ellipses for each energy level

for i, n in enumerate(n_values):

E_n = hbar * omega * (n + 0.5)

a = np.sqrt(2 * E_n / (m * omega**2)) # x_max

b = np.sqrt(2 * m * E_n) # p_max

theta = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 500)

x = a * np.cos(theta)

p = b * np.sin(theta)

ax.plot(x, p, label=f"n = {n}", color=colors[i])

# Area of ellipse = πab (quasi-classical action)

A_n = np.pi * a * b

areas.append((n, A_n / h)) # normalized by h

# Annotate areas

for n, A_h in areas:

ax.text(0.1, 1.1 * np.sqrt(2 * m * hbar * omega * (n + 0.5)),

f"$A/h$ ≈ {A_h:.1f}", fontsize=9)

# Final plot settings

ax.set_xlabel("Position $x$")

ax.set_ylabel("Momentum $p$")

ax.set_title("Harmonic Oscillator Phase Space: Quasi-Classical Area $\oint p \\, dx$")

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

<>:44: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\o'

<>:44: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\o'

/tmp/ipykernel_2950/746595933.py:44: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\o'

ax.set_title("Harmonic Oscillator Phase Space: Quasi-Classical Area $\oint p \\, dx$")

Computing Z via classical mechanics¶

In quantum mechanics counting microsites is easy, we have discrete energies and could simply sum over microstates to compute partition functions

Counting microstates in classical mechanics is therefore done by discretizing phase space for N particle system into smallest unit boxes of size .

Once agan to correct classical mechanics for “double counting” of microstates if we have N indistinguishable “particles” with a factor of

The power and utility of NVT: The non-interacting system¶

For the independent particle system, the energy of each particle enter the total energy of the system additively.

The exponential factor in the partition function allows decoupling particle contributions . This means that the partition function can be written as the product of the partition functions of individual particles!

Distinguishable states:

Indistinguishable states:

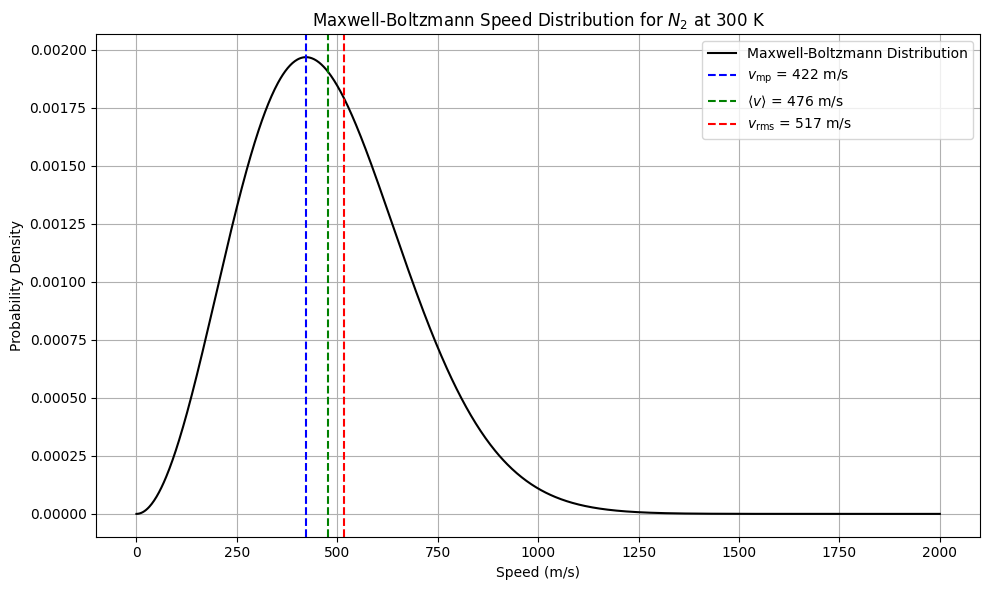

Maxwell-Boltzman distribution¶

Since the kinetic and potential energy functions depend separately on momenta and positions, the total probability distribution factorizes into a product of position and momentum distributions:

This separation leads to:

The intergarlwith position-dependent potential for interacting particle system is impossible to evaluate except by simulations or numerical techniques

The momentum-dependent part splits into individaul integrals for every particle and is always a simple quadratic function, making it analytically tractable:

The momentum (or velocity) distribution follows the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution in all equilibrium systems, regardless of the complexity of the molecular interactions.

Maxwell-Boltzmann Velocity Distribution: Full Derivation

Separation of variables

In equilibrium, the distribution of velocities in the , , and directions are independent and identical, because there’s no preferred direction in an ideal gas. Therefore, we can write the joint probability distribution as:

Furthermore, the probability of finding a particle with velocity components between , , and is:

Form of the velocity component distribution

The system is in thermal equilibrium, so the probability of a particle having a certain velocity corresponds to the Boltzmann factor for its kinetic energy:

For a single particle of mass , the kinetic energy is:

So we postulate:

Using the independence of the components:

We require that:

This is a standard Gaussian integral of form where and therefore we write down:

Distribution of speeds

Now, let’s consider the speed .

The probability density for the speed (regardless of direction) is obtained by converting to spherical coordinates in velocity space. The volume element in velocity space becomes:

Integrating over angles gives a factor of :

Substitute in the expressions for , , and , and recall that the total exponent is:

Therefore, the speed distribution is:

This is the Maxwell-Boltzmann speed distribution. It gives the probability density that a particle in a gas has speed .

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Constants for Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution (in arbitrary units)

k_B = 1.38e-23 # Boltzmann constant (J/K), not used directly since we'll use reduced units

T = 300 # Temperature in K

m = 4.65e-26 # Mass of nitrogen molecule (kg), approximate

# Define velocity range

v = np.linspace(0, 2000, 1000)

# Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution function

def f_MB(v, m, T):

return 4 * np.pi * v**2 * (m / (2 * np.pi * k_B * T))**(3/2) * np.exp(-m * v**2 / (2 * k_B * T))

# Compute distribution

f_v = f_MB(v, m, T)

# Characteristic velocities

v_mp = np.sqrt(2 * k_B * T / m) # Most probable speed

v_avg = np.sqrt(8 * k_B * T / (np.pi * m)) # Average speed

v_rms = np.sqrt(3 * k_B * T / m) # Root mean square speed

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(v, f_v, label="Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution", color='black')

plt.axvline(v_mp, color='blue', linestyle='--', label=f"$v_{{\\rm mp}}$ = {v_mp:.0f} m/s")

plt.axvline(v_avg, color='green', linestyle='--', label=f"$\\langle v \\rangle$ = {v_avg:.0f} m/s")

plt.axvline(v_rms, color='red', linestyle='--', label=f"$v_{{\\rm rms}}$ = {v_rms:.0f} m/s")

plt.title("Maxwell-Boltzmann Speed Distribution for $N_2$ at 300 K")

plt.xlabel("Speed (m/s)")

plt.ylabel("Probability Density")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Ideal Gas¶

A useful approximation is to consider the limit of a very dilute gas, known as an ideal gas, where interactions between particles are neglected .

Lets evaluate partition function for a single atom of idea gas:

On the Validity of the Classical Approximation

The classical approximation is valid when the average interatomic spacing is much larger than , i.e., when:

This ensures that wavefunction overlap is negligible and particles behave classically.

We can also calculate entropy and other thermodynamic quantities and compare with expressions obtained in ensemble

Equipartition Theorem¶

Consider a classical system with a Hamiltonian containing a quadratic degree of freedom , such that:

The canonical partition function for this degree of freedom is:

The average energy is:

Examples¶

Monatomic ideal gas: 3 translational degrees →

Diatomic molecule at high : 3 translational + 2 rotational + active vibrational modes

→

Partition functions for non-interacting molecules¶

Total energy and partition function for a molecule with separable degrees of freedom:

Translational Degrees of Freedom: Particle in a Box¶

For a particle in a 3D box of volume , the energy levels are:

To approximate the partition function at high temperatures (many levels populated), we replace the discrete sum with an integral:

This is a Gaussian integral:

For indistinguishable molecules we obtain same result we go for ideal gas!

Rotational Degrees of Freedom: Rigid Rotor Model¶

For a linear molecule (diatomic rotor), the rotational energy levels are:

The partition function is:

At high temperatures (), this sum can be approximated as an integral:

Let for large :

This integral is:

Where is the rotational temperature.

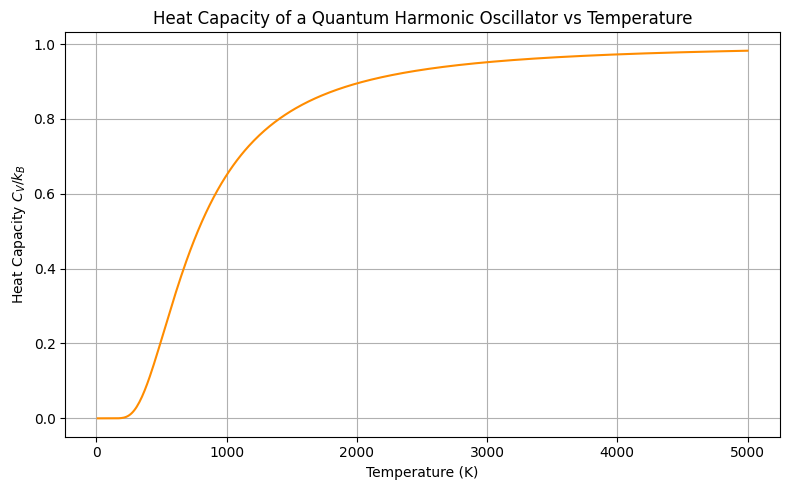

Vibrational Degrees of Freedom: Harmonic Oscillator Model¶

Partition function for one oscillator:

For independent oscillators:

Average energy would then be:

Low and high temperature behaviours of harmonic oscillators¶

Notice the two important limits. At low temperature quantization of energy becomes important while at high temperature result matches with classical mechanics predictions;

As , , so:

As , :

Source

# Temperature range in Kelvin

T_vals = np.linspace(10, 5000, 500)

# Vibrational frequency (typical for molecular vibration)

# Use hbar*omega = energy quantum = ~0.2 eV (~3200 cm^-1 IR band), convert to J

hbar_omega = 0.2 * 1.602e-19 # in J

# Dimensionless variable x = hbar*omega / (k_B * T)

x = hbar_omega / (k_B * T_vals)

# Heat capacity C_v of harmonic oscillator (per mode)

# C_v = k_B * (x^2 * exp(x)) / (exp(x) - 1)^2

C_v = k_B * (x**2 * np.exp(x)) / (np.exp(x) - 1)**2

# Convert C_v to units of k_B

C_v_over_kB = C_v / k_B

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.plot(T_vals, C_v_over_kB, color='darkorange')

plt.xlabel("Temperature (K)")

plt.ylabel("Heat Capacity $C_V / k_B$")

plt.title("Heat Capacity of a Quantum Harmonic Oscillator vs Temperature")

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

On heat capacity of harmonic-oscillators¶

Einstein Model of solids¶

A simple model for solids due to Einstein describes it as independent harmonic oscillators representing localized atomic vibrations.

The average energy of a quantum harmonic oscillator is:

The heat capacity is the derivative:

Key predictions of Einstein model of solids¶

At low T: — the oscillator is frozen in its ground state.

At high T: — classical equipartition is recovered.

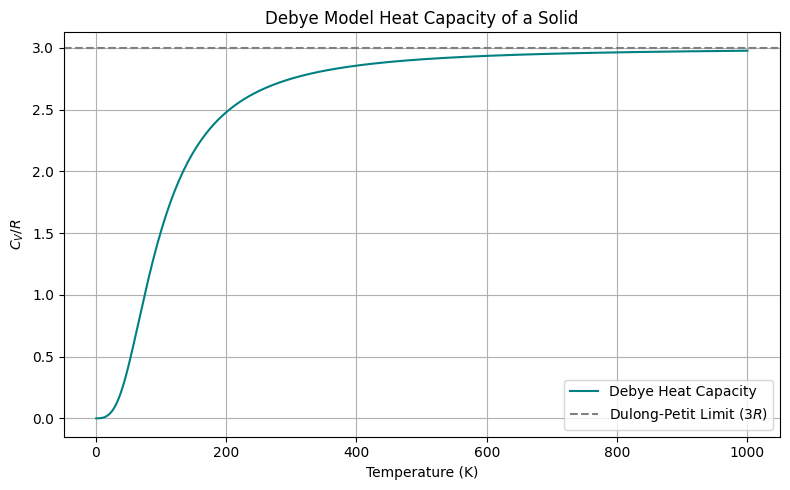

Debye Model of Solids¶

The Debye model improves upon Einstein’s and matches experimental data much better than the Einstein model, especially at low temperatures.

Main distinguishing features of Debye model are:

Treating atomic vibrations as a continuum of phonon modes.

Including a full spectrum of frequencies up to a Debye cutoff .

Predicting the correct low-temperature behavior of solids.

Behavior of Debye Model¶

Low T: — from long-wavelength (acoustic) phonons.

High T: — classical limit.

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.integrate import quad

# Constants

k_B = 1.38e-23 # Boltzmann constant (J/K)

N_A = 6.022e23 # Avogadro's number

R = N_A * k_B # Gas constant (J/mol·K)

# Debye model parameters

T_D = 400 # Debye temperature in Kelvin (can be adjusted)

# Debye heat capacity function

def debye_integral(x_D):

integrand = lambda x: (x**4 * np.exp(x)) / (np.exp(x) - 1)**2

val, _ = quad(integrand, 0, x_D)

return val

# Temperature range

T_vals = np.linspace(1, 1000, 300)

C_v_debye = []

# Calculate heat capacity at each temperature

for T in T_vals:

x_D = T_D / T

if T == 0:

C_v_debye.append(0)

else:

integral = debye_integral(x_D)

C_v = 9 * R * (T / T_D)**3 * integral

C_v_debye.append(C_v)

# Convert to numpy array

C_v_debye = np.array(C_v_debye)

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.plot(T_vals, C_v_debye / R, color='teal', label="Debye Heat Capacity")

plt.axhline(3, color='gray', linestyle='--', label="Dulong-Petit Limit ($3R$)")

plt.xlabel("Temperature (K)")

plt.ylabel("$C_V / R$")

plt.title("Debye Model Heat Capacity of a Solid")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

/tmp/ipykernel_2950/174881513.py:15: RuntimeWarning: overflow encountered in scalar power

integrand = lambda x: (x**4 * np.exp(x)) / (np.exp(x) - 1)**2

Problems¶

Problem-1 1D energy profiles¶

Given an energy function with constants

Compute free energy difference between minima at temperature

Compute free energy around minima of size

Problem-2 Maxwell-Boltzman¶

You are tasked with analyzing the behavior of non-interacting nitrogen gas molecules described by Maxwell-Boltzman distirbution:

Where:

is the probability density for molecular speed

is the mass of a nitrogen molecule

(Boltzmann constant)

is the temperature in Kelvin

Step 1: Plot the Maxwell-Boltzmann Speed Distribution

At room temperature (T = 300, 400, 500, 600 K), plot the distribution for speeds ranging from 0 to 2000 m/s.

Step 2: Identify Most Probable, Average, and RMS Speeds

Compute and print:

The most probable speed

The mean speed

The root mean square (RMS) speed

Plot vertical lines on your plot from Step 1 to show these three characteristic speeds.

Step 3: Speed Threshold Analysis

Use numerical integration to calculate the fraction of molecules that have speeds:

(a) Greater than 1000 m/s

(b) Between 500 and 1000 m/s

Hint: Use

scipy.integrate.quadto numerically integrate the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Problem-3 Elastic Collisions¶

In this problem need to modify the code to add elastic collisions to the ideal gas simulations

Problem-4 Elementary derivation of Boltzmann’s distirbution¶

Let us do an elementary derivation of Boltzman distribution showing that when a macroscopic system is in equilibrium and coupled to a heat bath at temperatere we have a universal dependence of probability for finding system at different energies:

The essence of the derivation is this. Consider a vertical column of gas somehre in the mountains.

On one hand we have graviational force which acts on a column between with cross section .

On the other hand we have pressure balance which thankfully keeps the molecules from dropping on the ground.

This means that we have a steady density of molecules at each distance for a fixed . Write down this balance of forces (gravitational vs pressure ) and find show how density at , is related to density at , .

Tip: you may use for pressure and for the gravitational force)

Problem-5 2D diploes on a lattice¶

Consider a 2D square lattice with lattice points. On each point we have a mangeetic moment that can point in four possible directions: . Along axis, the dipole has the energy and along the x axis .

Dipoles are not interacting with each other and we also ingnore kinetic energy of diplos since they are fixed at lattice positions.

Write down parition function for this system

Compute the average energy.

Compute entropy per dipole . Evaluate the difference ? Can you see a link with number of arrangements of dipols?

Compute microcanonical partition function

Show that we get the same entropy expression by using and ensembles.