Introducing random variables¶

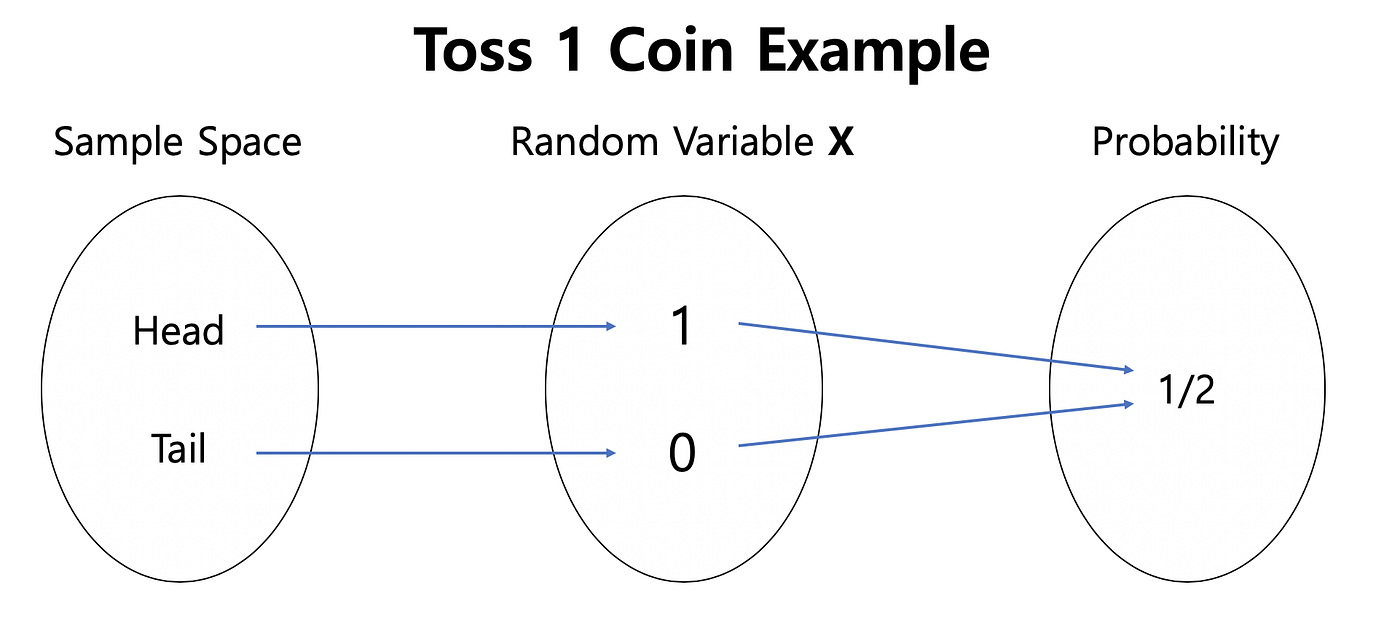

A random variable is what we interact with in experiments and simulations to infer probability distributions over the sample space.

A random variable X is a variable whose value depends on the realization of experiment or simulations.

is a function from possible outcomes of a sample space .

For a coin toss and . Every time the experiment is done, X returns either +1 or -1. We could also make functions of random variables, e.g., every time X=+1, we ear 25 cents, etc.

Random variables are classified into two main types: discrete and continuous.

Discrete Random Variable: It assumes a number of distinct values. Discrete random variables are used to model scenarios where outcomes can be counted, such as the number of particles emitted by a radioactive source in a given time interval or the number of photons hitting a detector in a certain period.

Continuous Random Variable: It can take any value within a continuous range. These variables describe quantities that can vary smoothly, such as the position of a particle in space, the velocity of a molecule in a gas, or the energy levels of an atom.

Random Numbers in Python¶

The numpy.random module provides highly efficient random number generators, implemented in optimized C code for fast performance.

The most commonly used random number generators in NumPy are:

np.random.rand()– Generates uniform random numbers in the interval ([0,1]).np.random.randn()– Generates standard normal (Gaussian) random numbers with a mean of 0 and variance of 1.

Since random numbers are inherently unpredictable, running the same code multiple times will produce different results. To ensure reproducibility, you can set a fixed random seed before generating random numbers using:

np.random.seed(8376743)Setting the seed ensures that the same sequence of random numbers is generated each time the code runs.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

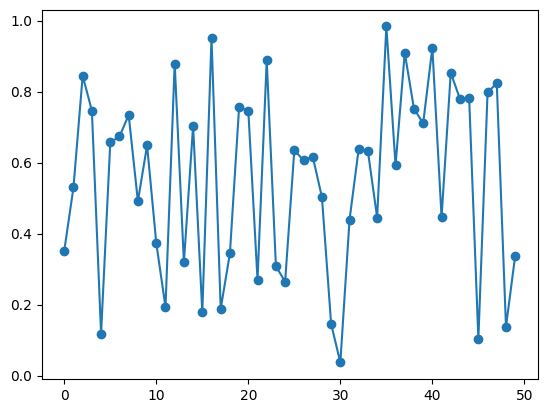

X = np.random.rand(50)

print(X)

plt.plot(X, '-o')[0.35170032 0.52980396 0.84473775 0.74641651 0.11807815 0.65673806

0.67354381 0.73399787 0.49090652 0.64856159 0.37298041 0.19285072

0.87919006 0.31865248 0.70279355 0.17761876 0.95146899 0.18809944

0.34427505 0.75653899 0.74652982 0.26959095 0.88815268 0.30775554

0.26423691 0.63535463 0.60586523 0.61712362 0.50242445 0.14534711

0.03670392 0.43906582 0.63951173 0.63128348 0.44523934 0.98352443

0.59210674 0.90956912 0.75223258 0.71049725 0.92327829 0.44568561

0.85353431 0.77897494 0.7813788 0.10268202 0.79814481 0.82331735

0.13730513 0.3371595 ]

Probability Distribution of a Random Variable¶

For any random variable , we are interested in finding the probability distribution over its possible values , denoted as .

It is important to distinguish between:

, which represents a specific value the variable can take (e.g., for a die).

, which is the random variable itself, generating values according to the probability distribution .

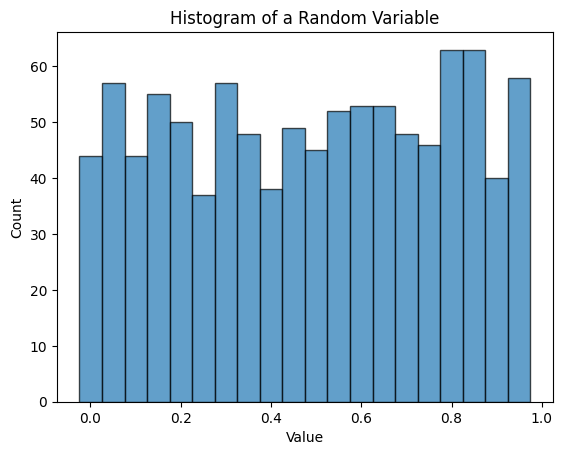

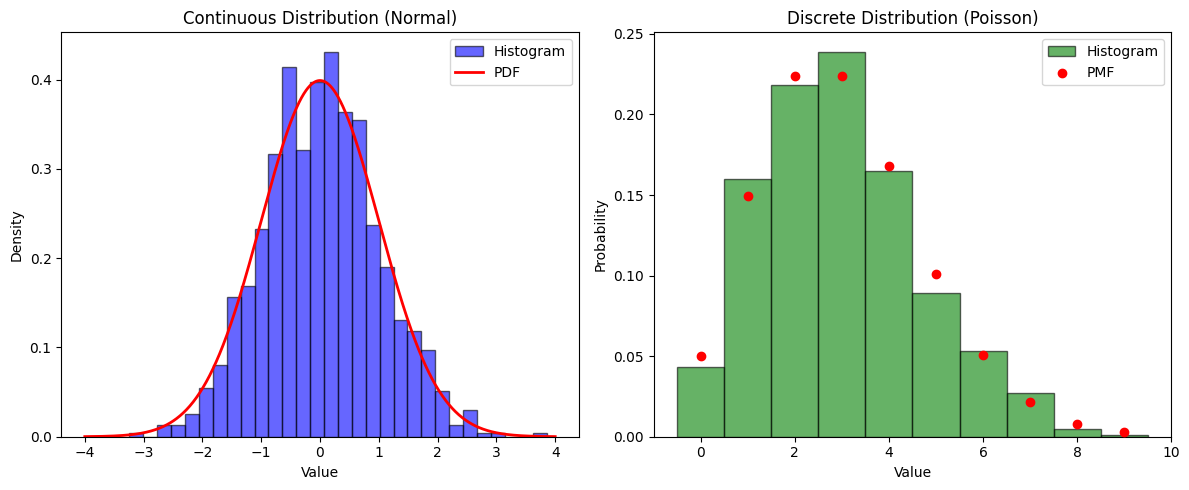

What is a Histogram

A histogram provides an empirical estimate of a distribution by grouping data into bins and counting occurrences within each bin.

For continuous distributions, histograms approximate the probability density function (PDF).

For discrete distributions, histograms approximate the probability mass function (PMF).

The choice of bin width significantly impacts visualization:

Too few bins can obscure details. Too many bins can introduce noise, making patterns less clear.

Histogramming in numpy

np.histogram(X, bins=20): Divides the range of values of X into e.g. 20 bins and counts how many data points fall into each bin. histogram returns:bin_edges: The boundaries of each bin.counts: The number of values in each bin.

Visualization

plt.bar(...): Plots the histogram using a bar chart.plt.hist(): Can directly plot histogram of random variableThe Seaborn library provides convenient visualization tools for random numbers. For example,

sns.histplot(np.random.randn(1000), kde=True)can be used to visualize the distribution of 1000 normally distributed random numbers with a smooth density curve.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Generate 1000 random values from a normal distribution

X = np.random.rand(1000)

# Compute the histogram using NumPy

counts, bin_edges = np.histogram(X, bins=20)

# Print the histogram X

print("Bin edges:", bin_edges)

print("Counts per bin:", counts)

# Plot the histogram

plt.bar(bin_edges[:-1], counts, width=np.diff(bin_edges), edgecolor='black', alpha=0.7)

plt.xlabel("Value")

plt.ylabel("Count")

plt.title("Histogram of a Random Variable")

plt.show()Bin edges: [7.05094253e-04 5.06422576e-02 1.00579421e-01 1.50516584e-01

2.00453748e-01 2.50390911e-01 3.00328074e-01 3.50265238e-01

4.00202401e-01 4.50139565e-01 5.00076728e-01 5.50013891e-01

5.99951055e-01 6.49888218e-01 6.99825381e-01 7.49762545e-01

7.99699708e-01 8.49636871e-01 8.99574035e-01 9.49511198e-01

9.99448362e-01]

Counts per bin: [44 57 44 55 50 37 57 48 38 49 45 52 53 53 48 46 63 63 40 58]

Show that 1D histogram above is normalized!

Do it for a 2D gaussian distribution

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import norm, poisson

import seaborn as sns

# Generate data for continuous distribution (Normal)

np.random.seed(42)

x_continuous = np.random.normal(loc=0, scale=1, size=1000)

# Generate data for discrete distribution (Poisson)

x_discrete = np.random.poisson(lam=3, size=1000)

# Define x values for theoretical curves

x_cont_range = np.linspace(-4, 4, 1000)

x_disc_range = np.arange(0, 10)

# Plot histograms

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Continuous distribution (Normal)

axes[0].hist(x_continuous, bins=30, density=True, alpha=0.6, color='b', edgecolor='black', label="Histogram")

axes[0].plot(x_cont_range, norm.pdf(x_cont_range, loc=0, scale=1), 'r-', lw=2, label="PDF")

axes[0].set_title("Continuous Distribution (Normal)")

axes[0].set_xlabel("Value")

axes[0].set_ylabel("Density")

axes[0].legend()

# Discrete distribution (Poisson)

axes[1].hist(x_discrete, bins=np.arange(11)-0.5, density=True, alpha=0.6, color='g', edgecolor='black', label="Histogram")

axes[1].scatter(x_disc_range, poisson.pmf(x_disc_range, mu=3), color='r', label="PMF", zorder=3)

axes[1].set_title("Discrete Distribution (Poisson)")

axes[1].set_xlabel("Value")

axes[1].set_ylabel("Probability")

axes[1].legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Expectation and Variance¶

The expectation of a random variable, , represents the theoretical mean, distinguishing it from the sample mean computed in simulations.

For example, consider the difference between:

The average height of people computed from a sample of cities.

The true mean height of the entire world population.

As the sample size increases, the sample mean converges to the expectation.

Expectation can be applied to variable or any function .

An important type of expectation is applied to the square of mean subtracted which quantifies variance, or fluctuations of .

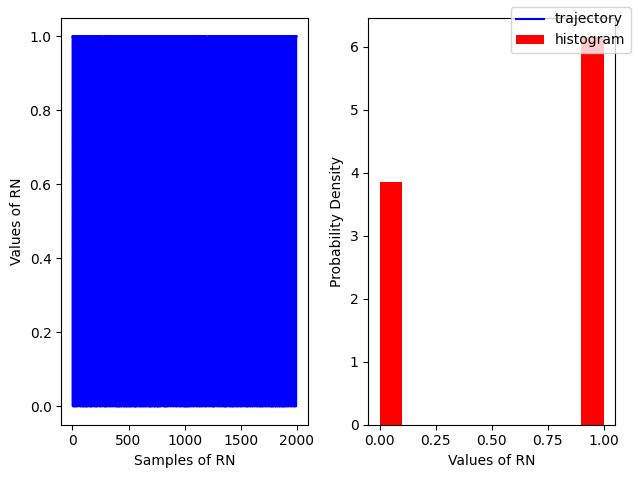

Binomial¶

A an example of discrete distribution Binomial is defined by a Probability Mass Function (PMF)

Random Variable

modeled by

np.random.binomial(n, p, size)

Source

r = np.random.binomial(n=1, p=0.6, size=2000)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=2)

ax[0].plot(r, color='blue', label='trajectory')

ax[1].hist(r, density=True, color='red', label = 'histogram')

ax[0].set_xlabel('Samples of RN')

ax[0].set_ylabel('Values of RN')

ax[1].set_xlabel('Values of RN')

ax[1].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

fig.legend();

fig.tight_layout()

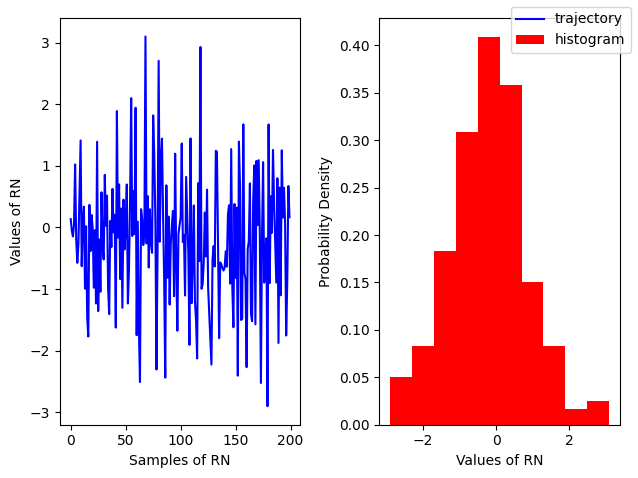

Gaussian¶

A an example of continuous distribution Gaussian is defined by a Probability Distribution Function

Random Variable

modeled by

np.random.normal(loc,scale, size=(N, M))modeled by

np.random.randn(N, M, P, ...)

Source

# For a standard normal with sigma=1, mu=0

r = np.random.randn(200)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=2)

ax[0].plot(r, color='blue', label='trajectory')

ax[1].hist(r, density=True, color='red', label = 'histogram')

ax[0].set_xlabel('Samples of RN')

ax[0].set_ylabel('Values of RN')

ax[1].set_xlabel('Values of RN')

ax[1].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

fig.legend();

fig.tight_layout()

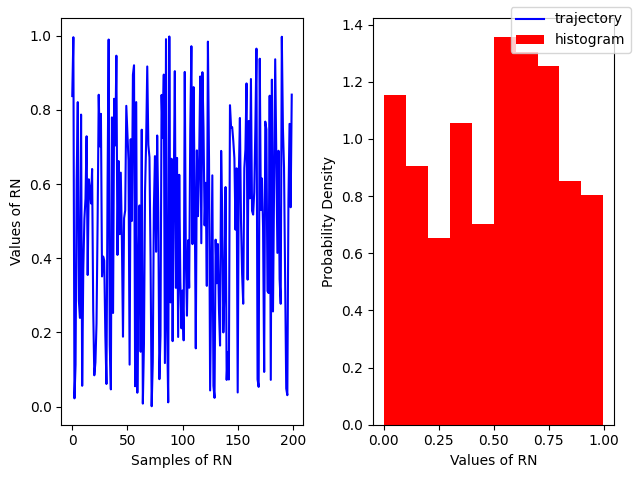

Uniform Distribution¶

A simple example of a continuous distribution is the Uniform distribution, where all values within a given range are equally likely. It is defined by the Probability Density Function (PDF):

Expectation and Variance:

Random Variable

is modeled by:

np.random.uniform(low, high, size=(N, M))(standard uniform) is modeled by:

np.random.rand(N, M, P, ...)

Source

# For a standard uniform

r = np.random.random(200)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=2)

ax[0].plot(r, color='blue', label='trajectory')

ax[1].hist(r, density=True, color='red', label = 'histogram')

ax[0].set_xlabel('Samples of RN')

ax[0].set_ylabel('Values of RN')

ax[1].set_xlabel('Values of RN')

ax[1].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

fig.legend();

fig.tight_layout()

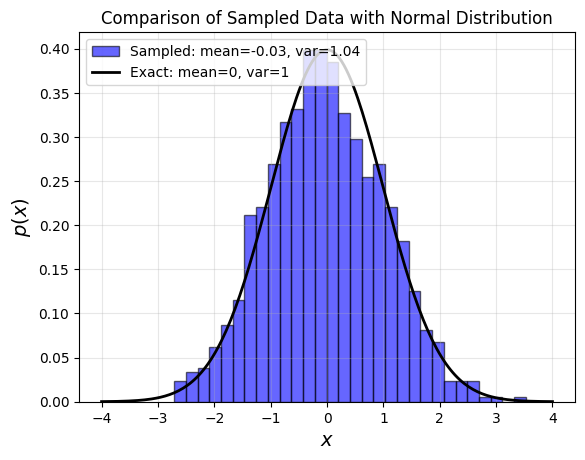

Exact vs sampled probability distributions¶

Source

# Simplified and optimized version of the code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import norm

# Generate x values and compute standard normal PDF

x = np.linspace(-4, 4, 200)

px = norm.pdf(x)

# Generate random samples

r = np.random.randn(1000)

# Plot histogram and theoretical normal distribution

plt.hist(r, bins=30, density=True, alpha=0.6, color='blue', edgecolor='black',

label=f'Sampled: mean={r.mean():.2f}, var={r.var():.2f}')

plt.plot(x, px, 'k-', linewidth=2, label='Exact: mean=0, var=1')

# Formatting

plt.legend(loc="upper left", fontsize=10)

plt.xlabel(r'$x$', fontsize=14)

plt.ylabel(r'$p(x)$', fontsize=14)

plt.title("Comparison of Sampled Data with Normal Distribution", fontsize=12)

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

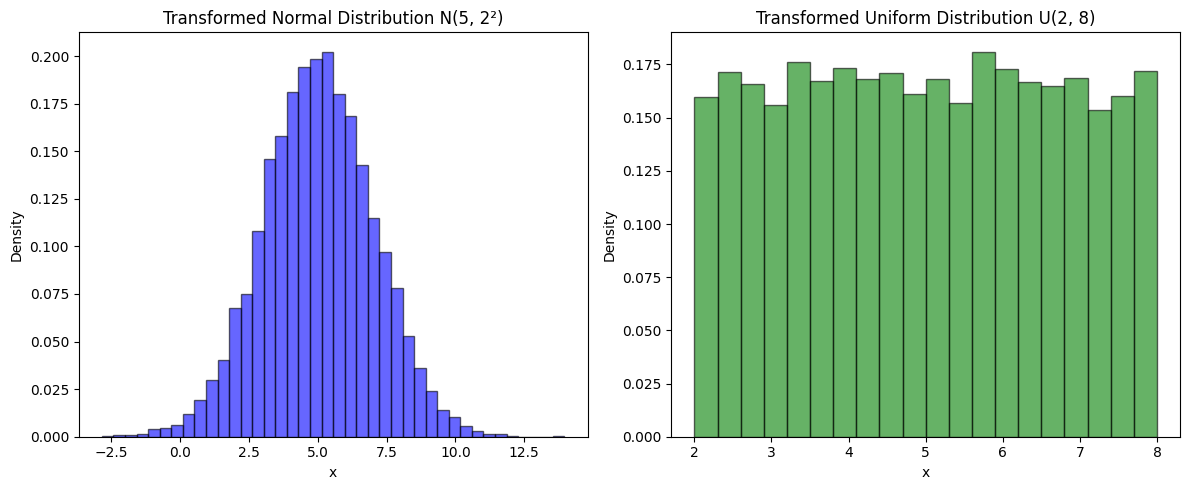

Transforming Random Variables¶

When a random variable is transformed by adding, multiplying by a constant, or applying a function , its probability distribution changes accordingly from to .

Two commonly used transformations involve multiplying or adding constants to random variables:

Generating a Gaussian (Normal) distribution from a standard normal:

Generating a Uniform distribution from a standard uniform:

Transforming Random Variables

When transforming a random variable to a new variable , the probability density functions are related by a Jacobian factor to account for how the transformation stretches or compresses the distribution:

which gives:

Examples of Simple Transformations:

Addition:

The probability remains unchanged except for a shift:

Multiplication:

The distribution scales with a factor :

These transformations yield useful properties:

Shifting the Mean:

Scaling the Variance:

Using these properties, we can generate:

A Gaussian (Normal) distribution from a standard normal:

A Uniform distribution from a standard uniform:

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Parameters

mu, sigma = 5, 2 # Mean and standard deviation for Gaussian

a, b = 2, 8 # Bounds for Uniform

# Generate standard distributions

std_normal = np.random.randn(10000) # N(0,1)

std_uniform = np.random.rand(10000) # U(0,1)

# Transform distributions

normal_dist = mu + sigma * std_normal # N(mu, sigma^2)

uniform_dist = a + (b - a) * std_uniform # U(a, b)

# Plot Distributions

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Normal Distribution

axes[0].hist(normal_dist, bins=40, density=True, alpha=0.6, color='b', edgecolor='black')

axes[0].set_title(f"Transformed Normal Distribution N({mu}, {sigma}²)")

axes[0].set_xlabel("x")

axes[0].set_ylabel("Density")

# Uniform Distribution

axes[1].hist(uniform_dist, bins=20, density=True, alpha=0.6, color='g', edgecolor='black')

axes[1].set_title(f"Transformed Uniform Distribution U({a}, {b})")

axes[1].set_xlabel("x")

axes[1].set_ylabel("Density")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Sum of Two Random Variables¶

Consider the sum of two random variables, such as:

The sum of numbers obtained from rolling two dice.

The sum of two coin flips (e.g., heads = 1, tails = 0).

Sum of kinetic eneries of ideal gas.

The sum of random variables is itself a random variable!

We want to understand how to described the properties of summed random variables as they offer a prototype of how large systems emerge froms mall components.

Given probability distirbution of and how do we find probability distribution of X?

Play with sums of RVs

Take unifiorm random number between 0 an 1. Generate 10, 20, 100 and see how are they behaving. Here are some helpful tips to generate Random Variables.

np.random.random(n)generates array of random variables of sizenp.random.random((n, m))generates array of random variables of shape

Expectation and Variance of the Sum¶

Expectation is always a linear operator, which follows from the definition of expectation and the linearity of integration:

However, variance is not generally a linear operator. To see this let us write explicit formula first:

Defining the mean-subtracted variables: we express variance of sum in terms of variances of component random variables

Since , this simplifies to:

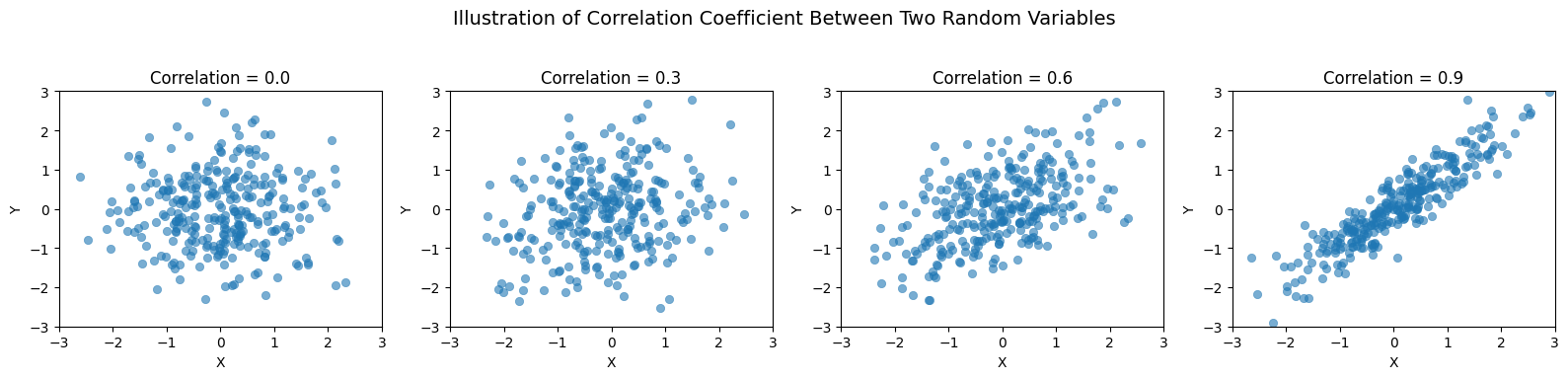

The cross term is called Covariance which measures the degree to which two random variables vary together.

To obtain a scale-independent measure, we then define the correlation coefficient. Corr the sign of which shows if correlation is positivie or negative.

In the special case where and are statistically independent, covariance (or correlation) is zero and we have additivity of variances!

This result is fundamental in statistical mechanics, probability theory, and the sciences, as it explains why variances add for independent random variables.

Source

import seaborn as sns

# Generate random data with different correlation coefficients

np.random.seed(42)

num_points = 300

# Define correlation levels

correlations = [0.0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9]

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, len(correlations), figsize=(16, 4))

for i, corr in enumerate(correlations):

mean = [0, 0]

cov_matrix = [[1, corr], [corr, 1]] # Covariance matrix based on correlation

data = np.random.multivariate_normal(mean, cov_matrix, num_points)

ax = axes[i]

sns.scatterplot(x=data[:, 0], y=data[:, 1], alpha=0.6, ax=ax, edgecolor=None)

ax.set_title(f'Correlation = {corr}', fontsize=12)

ax.set_xlabel('X')

ax.set_ylabel('Y')

ax.set_xlim(-3, 3)

ax.set_ylim(-3, 3)

# Overall title

plt.suptitle("Illustration of Correlation Coefficient Between Two Random Variables", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout(rect=[0, 0.03, 1, 0.95])

# Show the plot

plt.show()

Sum of Random Variables¶

Consider a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables, .

Since they are identically distributed, each variable has a well-defined mean and variance .

Our goal is to understand how the sum and mean of these variables depend on the sample size .

For convenience we also introduce notation for zero mean random variables , since

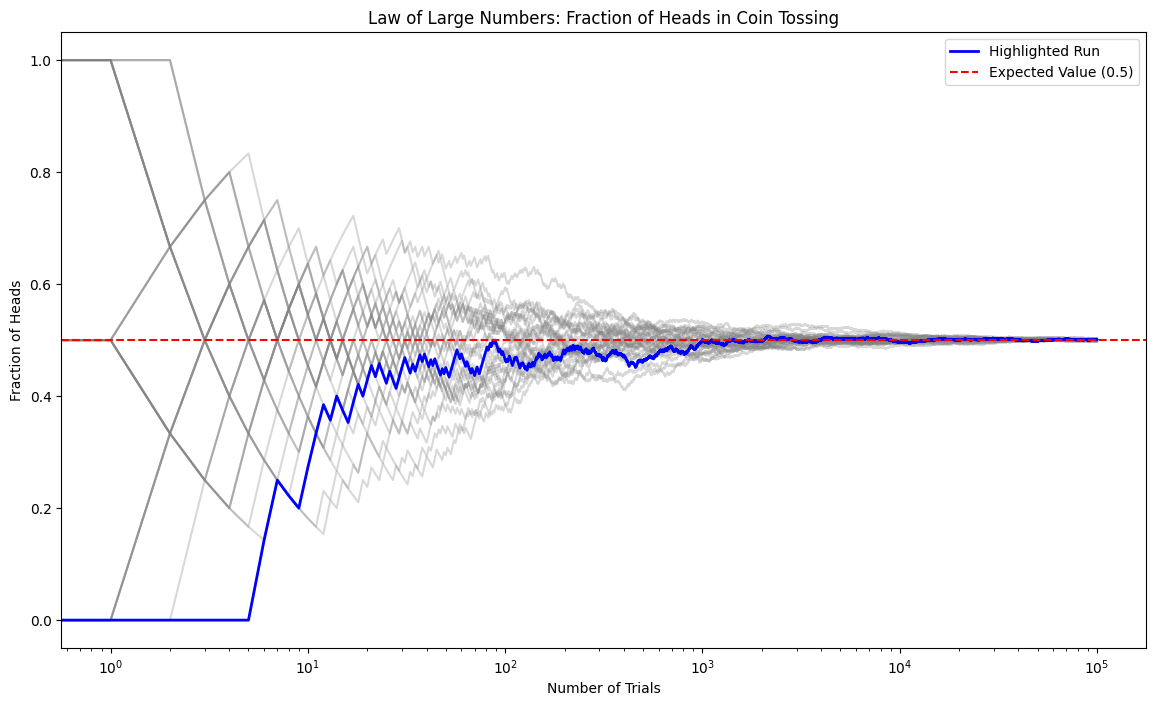

Law of Large Numbers¶

For the sample mean the result of summatiion of i.i.d variables is obtained by using multiplicative factor for random numbers that becomes for variance

Thus, the sample mean is an unbiased estimator of , and its variance decreases as , meaning that the estimate becomes more stable as increases.

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Number of trials and runs

N, runs = int(1e5), 30

# Store fractions of heads for each trial in each run

fractions = np.zeros((runs, N))

# Simulate coin tosses

for run in range(runs):

# Generate coin tosses (0 for tails, 1 for heads)

tosses = np.random.randint(2, size=N)

# Calculate cumulative sum to get the number of heads up to each trial

cum_heads = np.cumsum(tosses)

# Calculate fraction of heads up to each trial

fractions[run, :] = cum_heads / np.arange(1, N+1)

# Plotting

plt.figure(figsize=(14, 8))

# Plot all runs with low opacity

for run in range(runs):

plt.plot(fractions[run, :], color='grey', alpha=0.3)

# Highlight first run

plt.semilogx(fractions[0, :], color='blue', linewidth=2, label='Highlighted Run')

# Expected value line

plt.axhline(y=0.5, color='red', linestyle='--', label='Expected Value (0.5)')

plt.xlabel('Number of Trials')

plt.ylabel('Fraction of Heads')

plt.title('Law of Large Numbers: Fraction of Heads in Coin Tossing')

plt.legend()

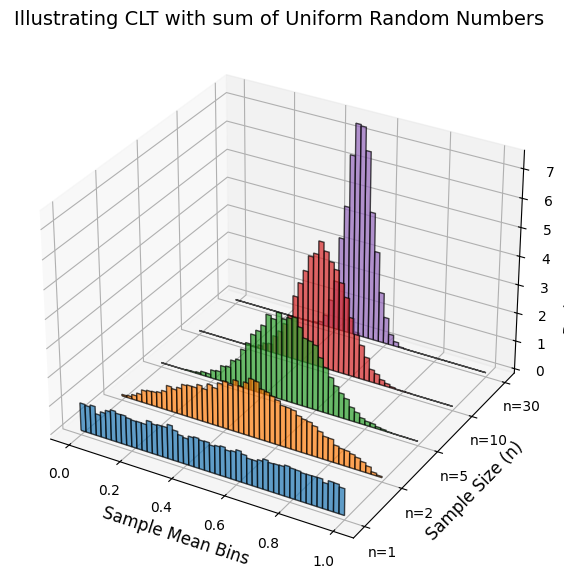

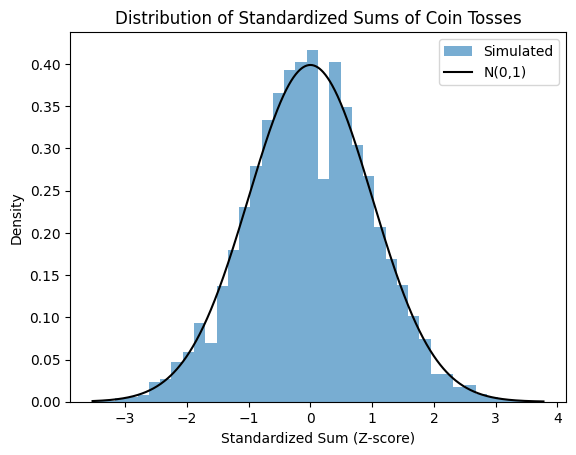

The Central Limit Theorem (CLT)¶

Central Limit Theorem asserts that the probability distribution function or PDF of sum of random variables becomes gaussian distribution with mean and .

Note that CLT is based on assumption that the mean and variance, and , are finite!. Thus, CLT does not hold for certain power-law distributed random variables.

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

# Parameters

num_samples = 10000 # Number of samples per distribution

num_bins = 50 # Number of bins for histogram

sample_sizes = [1, 2, 5, 10, 30] # Different sample sizes

bin_edges = np.linspace(0, 1, num_bins + 1)

# Create a figure with a 3D axis

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 7)) # Initialize the figure

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# Generate distributions and plot stacked histograms

for i, n in enumerate(sample_sizes):

samples = np.mean(np.random.uniform(0, 1, (num_samples, n)), axis=1) # Compute sample means

hist, bins = np.histogram(samples, bins=bin_edges, density=True)

# Centers of bins

bin_centers = (bins[:-1] + bins[1:]) / 2

# Offset along the y-axis for stacking

y_offset = i

# Plot histogram as bars

ax.bar(bin_centers, hist, zs=y_offset, zdir='y', alpha=0.7, width=0.02, edgecolor='black', label=f'n={n}')

# Labels and title

ax.set_xlabel('Sample Mean Bins', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Sample Size (n)', fontsize=12)

ax.set_zlabel('Probability Density', fontsize=12)

ax.set_yticks(range(len(sample_sizes)))

ax.set_yticklabels([f'n={n}' for n in sample_sizes])

ax.set_title("Illustrating CLT with sum of Uniform Random Numbers", fontsize=14)

plt.show()

Standardized random variables¶

The CLT motivates us to consuder dividing sum by and subtracting the mean which gives us another gaussian distributed variable, a more simple one with no parameters!

Notice that we are dividing the sum by . If we were to devide sum by then we have mean the variance of which goes. This would be Law of Large Numbers.

The process of de-meaning and scaling random variable by is called standardization which gives us standard random variabls defined as , and .

Source

from scipy.stats import norm

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Number of coin tosses in each experiment, number of experiments

N, runs = 1000, 10000

# Simulate coin tosses: num_experiments rows, num_tosses_per_experiment columns

tosses = np.random.randint(2, size=(N, runs))

# Calculate sums of each run

Sn = np.sum(tosses, axis=0)

# Compute numerical mean and standard deviation of Sn

mu_Sn = np.mean(Sn)

sigma_Sn = np.std(Sn, ddof=1) # Using sample standard deviation (ddof=1)

# Compute z-scores numerically

z = (Sn - mu_Sn) / sigma_Sn

# Plot histogram of z-scores

plt.figure()

plt.hist(z, density=True, bins=40, alpha=0.6, label="Simulated")

plt.title('Distribution of Standardized Sums of Coin Tosses')

plt.xlabel('Standardized Sum (Z-score)')

plt.ylabel('Density')

# Overlay standard normal distribution

zs = np.linspace(z.min(), z.max(), 1000)

plt.plot(zs, norm.pdf(zs), 'k', label='N(0,1)')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Example of CLT applied to random walk problem

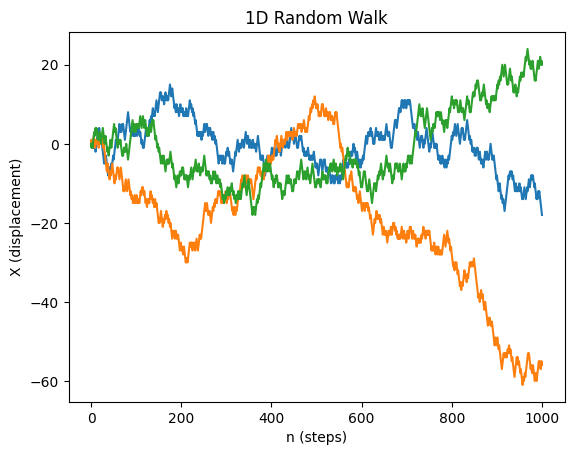

Simulating a 1D unbiased random walk¶

Each random walker will be modeled by a random variable , assuming +1 or -1 values at every step. We will run N random walkers (rows) over n steps (columns)

We then take cumulative sum over n steps thereby summing n random variables for N walkers. This will be done via a convenient

np.cumsum()method.

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def rw_1d(n, N):

"""

Simulates a 1D symmetric random walk.

Parameters:

n (int): Number of steps.

N (int): Number of walkers.

Returns:

np.ndarray: A (n, N) array where each column represents a walker's trajectory.

"""

# Generate random steps (-1 or +1) for all walkers

steps = np.random.choice([-1, 1], size=(n, N))

# Compute cumulative sum to get displacement

rw = np.cumsum(steps, axis=0)

# Ensure the initial position is zero

rw = np.vstack([np.zeros(N), rw]) # Adds a row of zeros at the start

return rw

# Example usage: Simulate and plot a few random walks

n_steps = 1000

n_walkers = 3

rw = rw_1d(n_steps, n_walkers)

plt.plot(rw)

plt.ylabel('X (displacement)')

plt.xlabel('n (steps)')

plt.title('1D Random Walk')

plt.show()

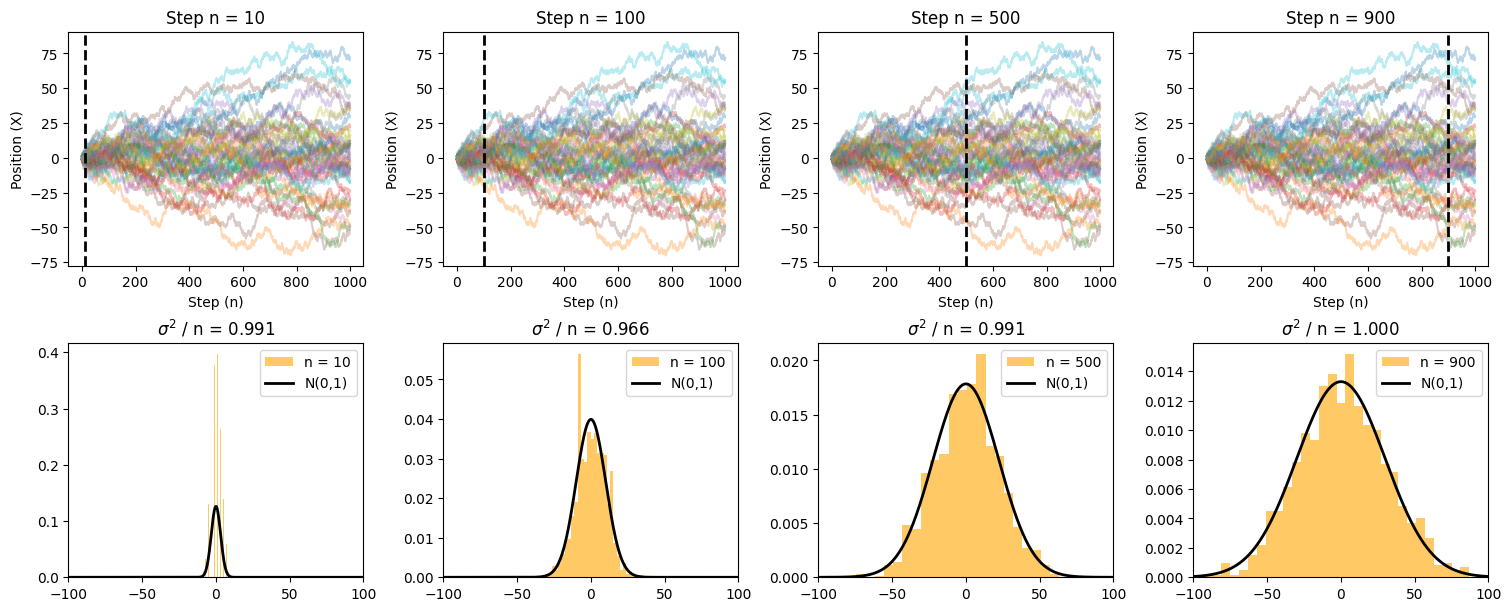

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

# Simulate 1D random walk

def rw_1d(n_max, N):

"""Generates a 1D random walk for N walkers over n_max steps."""

steps = np.random.choice([-1, 1], size=(n_max, N)) # Random steps

return np.cumsum(steps, axis=0) # Cumulative sum gives positions

# Parameters

n_max = 1000 # Number of steps

N_max = 1000 # Number of walkers

rw = rw_1d(n_max, N_max)

# Define time snapshots

snapshots = [10, 100, 500, 900]

# Create subplots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=len(snapshots), figsize=(15, 6), constrained_layout=True)

for i, n in enumerate(snapshots):

# Plot random walk trajectories

ax = axes[0, i]

ax.plot(rw[:, :50], alpha=0.3) # Show 50 trajectories for clarity

ax.axvline(x=n, color='black', lw=2, linestyle="--") # Mark current time step

ax.set_xlabel('Step (n)')

ax.set_ylabel('Position (X)')

ax.set_title(f'Step n = {n}')

# Histogram of positions at step n

ax_hist = axes[1, i]

ax_hist.hist(rw[n, :], bins=30, color='orange', density=True, alpha=0.6, label=f'n = {n}')

# Gaussian overlay

x = np.linspace(-100, 100, 1000)

y = stats.norm.pdf(x, loc=0, scale=np.sqrt(n))

ax_hist.plot(x, y, color='black', lw=2, label='N(0,1)')

ax_hist.set_xlim([-100, 100])

ax_hist.legend()

ax_hist.set_title(f'$\sigma^2$ / n = {np.var(rw[n - 1, :]) / n:.3f}')

# Show plot

plt.show()

<>:42: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\s'

<>:42: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\s'

/tmp/ipykernel_2748/3866549809.py:42: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\s'

ax_hist.set_title(f'$\sigma^2$ / n = {np.var(rw[n - 1, :]) / n:.3f}')

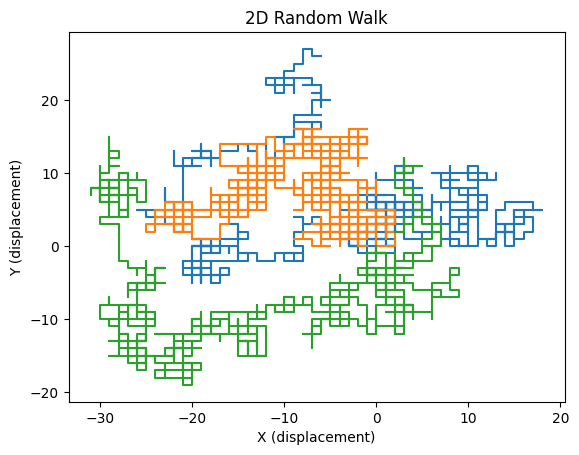

Source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def rw_2d(n, N):

"""

Simulates a 2D symmetric random walk.

Parameters:

n (int): Number of steps.

N (int): Number of trajectories.

Returns:

np.ndarray: A (n+1, N, 2) array where each trajectory is stored in the last dimension.

"""

# Define possible step directions (right, up, left, down)

steps = np.array([(1, 0), (0, 1), (-1, 0), (0, -1)])

# Generate random step indices and map to step directions

random_steps = steps[np.random.choice(4, size=(n, N))]

# Prepend an initial position at (0,0) for all walkers

rw = np.zeros((n + 1, N, 2), dtype=int)

rw[1:] = np.cumsum(random_steps, axis=0) # Compute displacement over time

return rw

# Example usage: Simulate and plot first three random walkers

n_steps = 1000

n_walkers = 100

traj = rw_2d(n_steps, n_walkers)

plt.plot(traj[:, :3, 0], traj[:, :3, 1]) # Plot first three random walkers

plt.xlabel('X (displacement)')

plt.ylabel('Y (displacement)')

plt.title('2D Random Walk')

plt.show()

Source

# Re-import necessary libraries due to execution state reset

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.animation as animation

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from IPython.display import HTML

# Parameters

num_steps = 200 # Number of steps in the random walk

step_size = 1 # Step size

# Generate random steps in 3D

np.random.seed(42)

steps = np.random.choice([-step_size, step_size], size=(num_steps, 3)) # Random steps in x, y, z

positions = np.cumsum(steps, axis=0) # Cumulative sum to get positions

# Create figure

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

ax.set_xlim([positions[:, 0].min()-1, positions[:, 0].max()+1])

ax.set_ylim([positions[:, 1].min()-1, positions[:, 1].max()+1])

ax.set_zlim([positions[:, 2].min()-1, positions[:, 2].max()+1])

ax.set_xlabel('X')

ax.set_ylabel('Y')

ax.set_zlabel('Z')

ax.set_title('3D Random Walk')

# Initialize the line and point

line, = ax.plot([], [], [], 'b-', lw=2)

point, = ax.plot([], [], [], 'ro')

# Update function for animation

def update(frame):

line.set_data(positions[:frame+1, 0], positions[:frame+1, 1])

line.set_3d_properties(positions[:frame+1, 2])

point.set_data([positions[frame, 0]], [positions[frame, 1]])

point.set_3d_properties([positions[frame, 2]])

return line, point

# Create animation

ani = animation.FuncAnimation(fig, update, frames=num_steps, interval=50, blit=False)

# Convert animation to HTML

html_anim = HTML(ani.to_jshtml())

plt.close(fig) # Prevent duplicate display

# Display the animation

html_anim

Animation size has reached 20986477 bytes, exceeding the limit of 20971520.0. If you're sure you want a larger animation embedded, set the animation.embed_limit rc parameter to a larger value (in MB). This and further frames will be dropped.

In class exercises

- Genrate random particle positions uniformly distributed in 1D. count how many end in right hand side. repeat experiments many times then histogram to ratio of particles that end in right hand side.

- Generate 1000 exponentially distributed random numbers. Show that their sum approaches gaussian. Convert it to unit normal distribution by rescaling.

- Show how to use standard uniform random number and transformation rules to generate +1/-1 random numbers.

- Create standard random numbers. Use tranformation properties to convert to gaussian distribution with different mean and sigma value

- Generate biased random walk by changing left/right probabilitiesProblems¶

Problem 1 Binomial as generator of Gaussian and Poisson distributions¶

Show that in large number limit binomial distribution tends to gaussian. Show is by expanding binomial distirbution in power series showing that terms beyond quadratic can be ignored.

In the limit but for very small values of such that there is another distribution that better approximates Binomial distribution: It is known as Poisson distribution.

Poisson distribution is an excellent approximation for probabilities of rare events. Such as, infrequently firing neurons in the brain, radioactive decay events of Plutonium or rains in the desert.

Derive Poisson distribution by taking the limit of in binomial distribution.Using numpy and matplotlib plot binomial probability distribution against Gaussian and Poisson distributions for different values of N=(10,100,1000,10000).

For a value N=10000 do four plots with the following values p=0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1. You can use subplot functionality to make a pretty 4 column plot. (See plotting module)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=4)

ax[0].plot()

ax[1].plot()

ax[2].plot()

ax[3].plot()Problem-2 Confined diffusion.¶

Simulate 2D random walk in a circular confinement. Re-write 2D random walk code to simulate diffusion of a particle which is stuck inside a sphere. Study how root mean square deviation of position scales with time.

Carry out simulations for different confinement sizes.

Make plots of simulated trajectories.

Problem-3 Return to the origin!¶

Simulate random walk in 1D and 2D for a different number of steps

Compute average number of returns to the origin . That is number of times a random walker returns to the origin 0 for 1D or (0,0)$ for 2D . You may want to use some 1000 trajectories to obtain average.

Plot how depends on number of steps N for 1D and 2D walker.

Problem-4 Breaking the CLT; Cauchy vs Normal random walk in 2D¶

For this problem we are going to simulate two kinds of random walks in continuum space (not lattice): Levy flights and Normal distributd random walk.

To simulate a 2D continuum space random walk we need to generate random step sizes , . Also you will need unifrom random namber to sample angles in 2D giving you a conitnuum random walk in 2D space: and

Normally:

Cauchy distribution (long tails, infinite variance)

Unform angles

Visualize random walk using matplotlib and study statistics of random walkers the way that is done for normal random walk/brownian motion examples!

Problem-5 Continuous time random walk (CTRW)¶

Simulate 1D random walk but instead of picking times at regular intervals pick them from exponential distribution.

Hint: you may want to use random variables from scipy.stats.exp

Study the root mean square deviation as a function of exponential decay parameter of exponential distribution .