Final Project: Metastability and Nucleation in the 2D Ising Model#

Background and Motivation#

In many physical systems, a state can appear stable for long times despite being thermodynamically unfavorable. Such states are called metastable. One familiar example is supercooled water—it remains liquid below the freezing point until a crystal nucleus forms and initiates freezing.

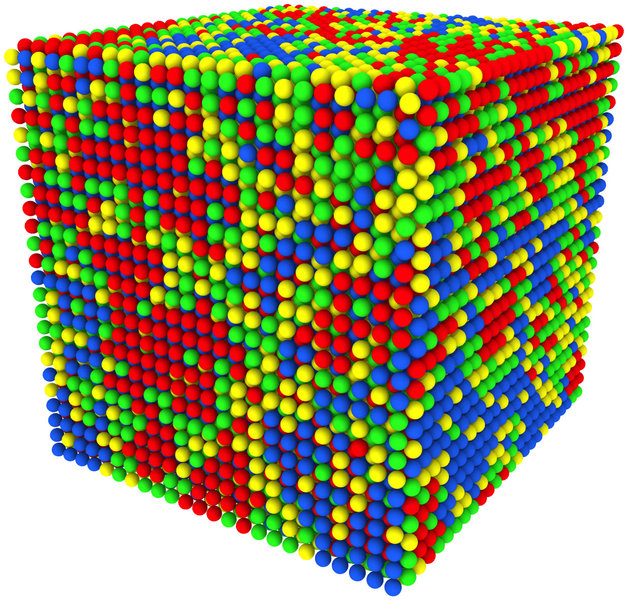

In this project, you will explore metastability and nucleation using the 2D Ising model. This model—originally developed to describe ferromagnetism—consists of a grid of spins \( s_i = \pm 1 \), with nearest-neighbor interactions and an external magnetic field \( h \). At temperatures below the critical temperature \( T_c \), the system tends to spontaneously align into one of two magnetized states. But what happens when the system is initially in a “wrong” state, e.g., aligned opposite to the magnetic field?

This setup creates a metastable state. It takes a rare fluctuation to nucleate a critical-size droplet of the stable phase, which then grows and flips the entire system. These types of processes are central to first-order phase transitions, nucleation in supersaturated vapors, and many biological self-assembly events.

Project Objective#

You will simulate a 2D Ising model below the critical temperature, with a small external magnetic field \( h < 0 \), starting from a fully \( +1 \)-magnetized state (aligned opposite to the field). Over time, the system will nucleate a region of the \( -1 \) phase, which may grow and flip the entire system.

You’ll study:

How the system escapes the metastable state.

The statistics of nucleation events.

The dependence of nucleation time on field strength and temperature.

The morphology of nucleating droplets.

Tasks#

Initial Setup and Simulation

Use the 2D Ising model with Metropolis Monte Carlo dynamics.

Set temperature \( T < T_c \) (e.g., \( T = 2.0 \), since \( T_c \approx 2.269 \) for the square lattice).

Add a small external magnetic field \( h < 0 \) (e.g., try \( h = -0.02, -0.05, -0.1 \)).

Initialize the system with all spins set to \( +1 \).

Observe Nucleation

Run the simulation for long times (thousands to millions of MC steps).

Monitor the magnetization \( M(t) \).

Plot sample trajectories where a rare nucleation event flips the sign of the magnetization.

Measure Nucleation Time

Repeat the simulation many times (e.g., 100–500 trials) to get statistics.

Measure the average time \( \langle \tau \rangle \) it takes for the system to reach negative magnetization.

Plot \( \langle \tau \rangle \) vs. field strength \( |h| \) (you should observe exponential dependence).

Analyze Droplet Formation

Record configurations just before the reversal event.

Visualize and classify droplet shapes.

Estimate typical droplet size at nucleation.

Discuss whether they appear compact (circular) or ramified (fractal-like).

Optional Challenge

Compare to Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT), which predicts: $\( \langle \tau \rangle \sim \exp\left(\frac{\Delta F_c}{k_B T}\right) \)\( where \) \Delta F_c $ is the free energy barrier to form a critical droplet.

Try estimating \( \Delta F_c \) from simulation data or using CNT formulas.

Learning Outcomes#

By the end of this project, you will:

Understand how metastability arises from energy barriers in statistical systems.

Observe and analyze rare-event dynamics and nucleation phenomena.

Learn techniques for sampling, averaging, and interpreting non-equilibrium trajectories.

Gain insight into how droplet shape and surface tension affect the stability of phases.

Appreciate the computational challenge of long timescales in simulating rare transitions.

Hints and Suggestions#

Use small system sizes at first (e.g., \( L = 32 \)) to speed up dynamics.

Save configurations intermittently to catch droplet formation visually.

Be patient—nucleation is rare! Consider parallelizing or running many short simulations instead of a few long ones.

You might consider implementing early termination when the magnetization crosses zero to save time.