Wave-particle duality#

What you need to know

Compton scattering and electron diffraction experiments have demonstrated that the concepts of particles and waves are not mutually exclusive.

A physical entity exhibits both wave-like (e.g., wavelength, interference, diffraction) and particle-like (e.g., momentum, collisions, countable) characteristics. For instance, an electron has a wavelength, while a photon has momentum.

The relationship between wave-like and particle-like characteristics is inversely proportional and is quantified by the de Broglie relation: \(\lambda = \frac{h}{p}\), where \(\lambda\) is the wavelength, \(h\) is Planck’s constant, and \(p\) is momentum.

Therefore, all quantum objects can behave as both waves and particles! The dominant behavior—wave-like or particle-like—depends on the specific experimental conditions.

Diffraction, interfernece and Double Slit experiment#

Fig. 25 Waves passing throw two slits and creating diffraction pattern on the screen.#

Diffraction: spreading of waves around obstacles or through small openings. Diffraction can occur with any type of wave, including light, sound, radio, and water.

Interference: when two waves meet one another their intensities either go up or go down if the two waves are in phase or out of phase, respectively.

Double slit experiment light waves (or water waves) are passing through a wall with two slits which results in wave-like interference patterns or bands on the detector screen.

Refraction and prisms#

Fig. 26 Example of light refracting when passing through a prism.#

Refraction: change in direction of propagation of any wave as a result of its traveling at different speeds at different points along the wave front.

For example, light bends when it travels from air to glass. The bending of light by refraction makes it possible for us to have lenses, magnifying glasses, prisms, and rainbows. Even our eyes depend upon this bending of light

Bragg’s formula for diffraction.#

X-rays interact with the atoms in a crystal. The phase shift upon scattering off of atoms causes constructive (left figure) or destructive (right figure) interferences.

Fig. 27 Example of light refracting when passing through a prism.#

Maxima and minima in interference patterns arise from simple geometry, as captured by Bragg’s law:

Bragg’s law:

\(d\): spacing between atomic planes in the lattice

\(\lambda\): wavelength of the radiation

\(n\): order of diffraction. For \(n=1\), the extra path length is one wavelength; for \(n=2\), it is two wavelengths, and so on. Higher-order reflections (\(n > 1\)) occur at larger angles and are usually weaker, so in practice most analyses focus on \(n=1\).

Waves such as X-rays produce interference patterns according to this relation. Historically, such interference was regarded as a hallmark of wave-like behavior.

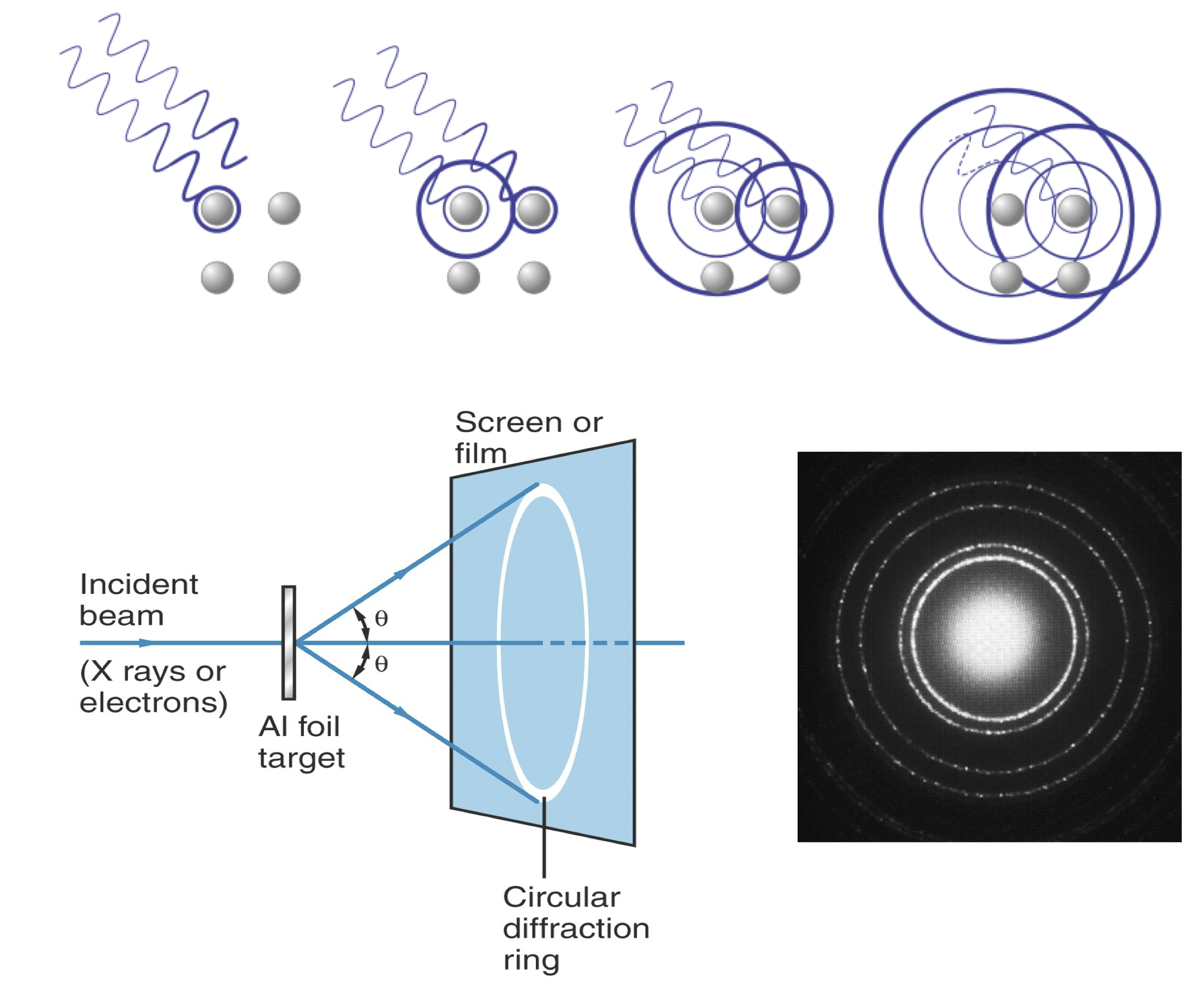

Both X-rays and electrons show diffraction patterns.#

Fig. 28 Demonstration of electron diffraction.#

In 1925, Davisson and Germer were studying electron scattering from various materials. To their great surprise, they discovered that at certain angles there was a peak in the intensity of the scattered electron beam.

This peak indicated wave behavior for the electrons and could be interpreted by Bragg’s law (previously only applied to X-ray scattering) to give values for the lattice spacing in the nickel crystal.

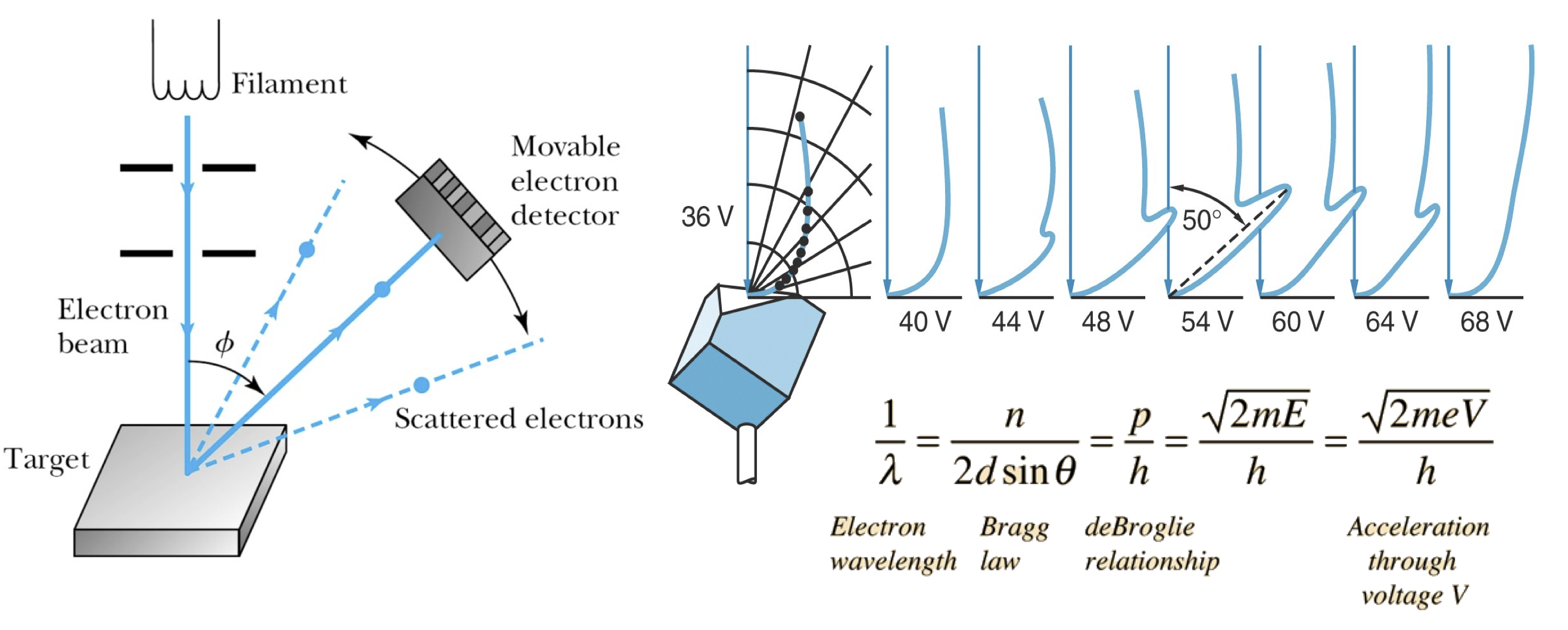

Compton scattering#

Fig. 29 Compton scattering: A phenomenon where photons scatter off electrons the same way other particles with mass do.#

Arthur Compton showed that X-rays get scattered off free electrons like elastic billiard balls. Applying conservation of momentum principle (previously only applied to particle-like objects), it was shown that the outgoing X-rays should be of longer wavelength than the incoming ones.

This means that a moving photon hits the resting free electron and transfers some energy to get the electron moving. Note that this experimental result makes sense only if you think of a photon as a particle with linear momentum which gets bounced off the electron.

De Broglie wavelength and wave-particle duality#

Light is a wave and a particle. An electron is also a particle and a wave. Is everything a wave and a particle? The answer is YES! This is what is meant by wave-particle duality. Sometimes we only see one side of the duality because under some conditions, either wave or particle characteristics are more pronounced.

The wave-like and particle-like characteristics of a physical entity are inversely proportional to each other as described by the de Broglie relationship.

De Broglie relation

Where \(h\): Planck’s constant. \(p\): the momentum of the object (electron, photon, molecule, chair, etc.). \(\lambda\): wavelength associated with the object.

The relation implies that heavy objects have a small wavelength, and light objects have a large wavelength.

The smaller the object, the more pronounced wave-like qualities it will have. And vice versa, the bigger the object, the more particle-like qualities it will have.

Effect of potential energy#

According to classical physics, the total energy for a particle is given as a sum of the kinetic and potential energies:

If we substitute de Broglie’s expression for momentum we get:

This equation shows that the de Broglie wavelength for particle like electron with constant total energy \(E\) would change as it moves into a region with different potential energy.

This has implications of chemical bonding where electrons experience different fields in atoms and molecules.

Double Slit experiment#

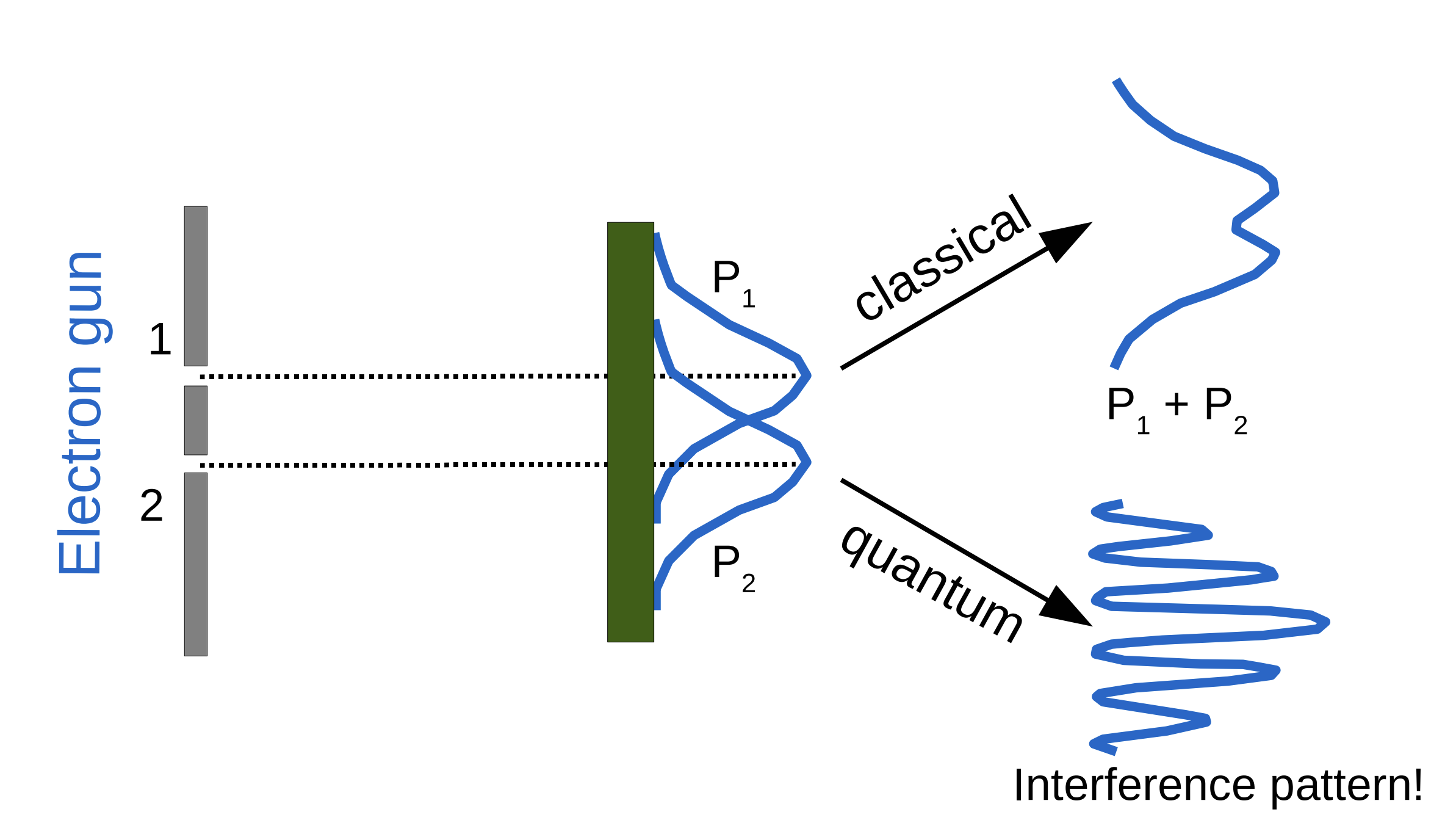

Fig. 30 Example of light refracting when passing through a prism.#

Electron displays wave like interference

The interference pattern would arise only if we consider electrons as waves, which interfere with each other (i.e. constructive and deconstructive interference)

When the experiment is carried out many times with only one electron going through the holes at once, we still observe the interference effect.

Fig. 31 Expectation of where electrons would fall based on classical vs quantum theories.#

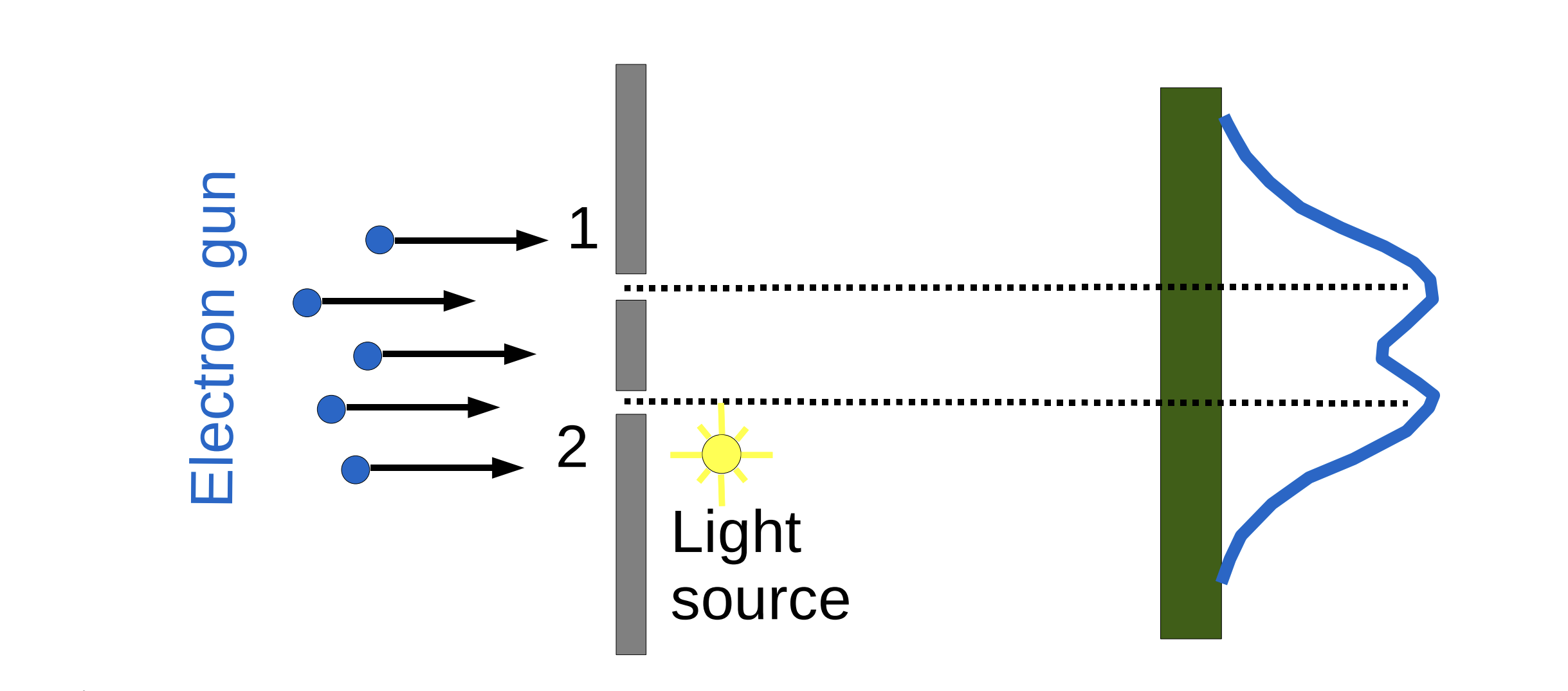

But which slit did the electron go through??

If we try to determine which way the electron traveled, the interference pattern disappears!

We will return to resolve this puzzle after establishing the formal theory of quantum mechanics and its postulates.

Fig. 32 Placing a detector that fires off photons to determine electron position exiting from slits.#

Uncertainty relation#

The uncertainty principle, also known as Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, states that it is impossible to measure the exact position and momentum of a particle at the same time. This principle is based on the wave-particle duality of matter

The principle states that the more precisely the position is known, the more uncertain the momentum is, and vice versa. For example, if we know everything about where a particle is located, we know nothing about its momentum.

Fig. 33 Demonstration of uncertainty principle. When electron position is localized by making the hole smaller its momentum becomes more unpredictable resulting in electrons hitting the detector over wider range.#

Mathematically uncertainly relation is expressed in terms of standard deviations of position \(\sigma_x\) and momenta \(\sigma_p\) which are quantified by doing repeat experiments measuring positions, momenta followed by quantifying the spread via standard deviation.

Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle

Problems#

Problem 1#

Estimate the wavelength of electrons that have been accelerated from rest through a potential difference of \(V = 40 kV\).

Note that potential energy difference that the electrons experience is simply \(e×V\) where e is the magnitude of electron charge and \(V\) potential difference.

Solution

In order to calculate the de Broglie wavelength, we need to calculate the linear momentum of the electrons. At the end of the acceleration, all the acquired energy is in the form of kinetic energy (\(p^2 / 2m_e\)).

Problem 2#

If you would consider yourself as a particle moving at \(2 m/s\), what would be your de Broglie wavelength? Would it make sense to use quantum mechanics in this case?

Solution

A. If you consider yourself as a particle moving at \(2 \, {m/s}\), we can calculate your de Broglie wavelength using the de Broglie relation:

where \(h\) is Planck’s constant, \(6.626 \times 10^{-34} \, {J·s}\), and \(p\) is the momentum of the object. The momentum is given by:

where \(m\) is your mass and \(v = 2 \, {m/s}\) is your velocity. Assuming your mass is \(70 \, {kg}\), the momentum would be:

Now, plugging the values into the de Broglie relation:

B. This wavelength is extremely small, much smaller than the scale at which quantum effects become noticeable. In this case, it wouldn’t make sense to use quantum mechanics, as classical mechanics is sufficient for describing the behavior of macroscopic objects like a person.

Problem 3#

Quantify uncertainty in position of electron in the ground state of H atom by using Bohr’s model.

Solution

To quantify the uncertainty in the position of an electron in the ground state of a hydrogen atom using Bohr’s model, we begin by recalling that the electron orbits the nucleus at a distance equal to the Bohr radius \(a_0\) in the ground state. The Bohr radius is given by:

where:

\(\varepsilon_0 = 8.854 \times 10^{-12} \, {F/m}\) (permittivity of free space),

\(\hbar = 1.055 \times 10^{-34} \, {J·s}\) (reduced Planck’s constant),

\(m_e = 9.109 \times 10^{-31} \, {kg}\) (mass of the electron),

\(e = 1.602 \times 10^{-19} \, {C}\) (elementary charge).

Substituting these values, we can calculate the Bohr radius:

Now, Bohr’s model treats the electron as orbiting at this radius with a known trajectory. However, quantum mechanics introduces the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which relates the uncertainties in position and momentum:

In the ground state, the uncertainty in momentum can be estimated from the momentum of the electron. The momentum \(p\) of the electron in the Bohr model is related to the velocity \(v\) and the mass \(m_e\):

Using the fact that the electron in the ground state has a velocity \(v \approx \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \varepsilon_0 \hbar} \approx 2.18 \times 10^6 \, {m/s}\), we can calculate the momentum:

Now, using the uncertainty relation:

Substituting \(\Delta p \approx p\), we get:

Thus, the uncertainty in the position of the electron in the ground state of a hydrogen atom is approximately \(2.65 \times 10^{-11} \, {m}\), which is on the order of the Bohr radius.

This result suggests that the electron’s position is spread out over a region approximately the size of the atom, supporting the idea that the electron in an atom cannot be described as a classical particle with a well-defined position.

Problem 4#

Quantify uncertainty in the position of electron traveling freely with kinetic energy of \(3 eV\)

Solution

To quantify the uncertainty in the position of an electron traveling freely with a kinetic energy of 3 eV, we can use the Heisenberg uncertainty principle:

First, we need to calculate the momentum of the electron. The kinetic energy is related to the momentum by the equation:

where:

\(K = 3 \, {eV} = 3 \times 1.602 \times 10^{-19} \, {J} = 4.806 \times 10^{-19} \, {J}\) (since \(1 \, {eV} = 1.602 \times 10^{-19} \, {J}\)),

\(m_e = 9.109 \times 10^{-31} \, {kg}\) is the mass of the electron.

Rearranging for momentum:

Substituting the values:

Now, using the Heisenberg uncertainty principle:

Assuming \(\Delta p \approx p\), we substitute the values:

Thus, the uncertainty in the position of the electron traveling with a kinetic energy of 3 eV is approximately \(4.48 \times 10^{-11}\) meters.

This is on the order of atomic scales, which indicates that quantum effects are relevant in this case.