The hydrogen molecule ion#

What you need to know

We can construct an approximate trial wavefunction for a molecule using atomic orbitals to gain intuition about chemical bonding.

Applying the variational method leads to two molecular orbitals (MOs) with distinct spatial character: one increases electron probability density between the nuclei (bonding), while the other decreases it (antibonding).

These bonding and antibonding MOs respectively lower and raise the energy of the molecule relative to two separated atoms.

More accurate quantum chemical methods do not rely directly on atomic orbitals, but instead use abstract linear combinations of Gaussian basis sets to represent molecular orbitals.

Constructing MOs from AOs#

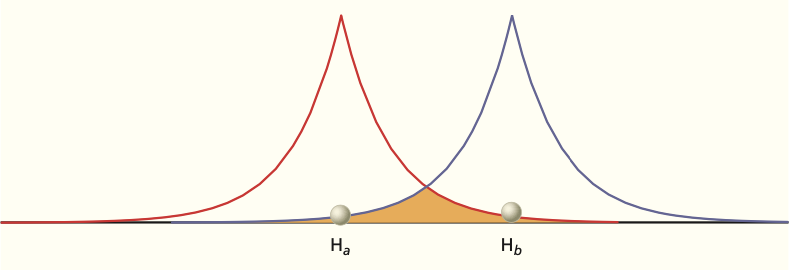

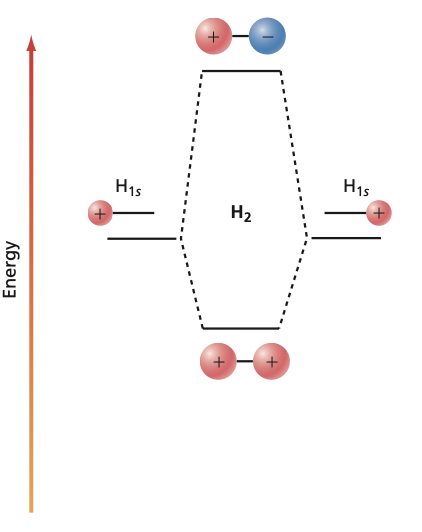

Fig. 102 AOs centered on each H atom in \(H^{+}_2\) molecule#

The electronic Schrödinger equation for H\(_2^+\) can be solved exactly because the system contains only a single electron. However, the analytical solution involves quite challenging mathematics. Instead, we will adopt a simpler approximate approach that still captures the essential physics of chemical bonding.

We construct a trial (approximate) molecular wavefunction as a real linear combination of hydrogen 1s atomic orbitals:

Here, \(1s_A\) and \(1s_B\) are hydrogen 1s orbitals centered on nuclei A and B, respectively, and \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are coefficients (constants).

This form is known as the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) approximation for constructing molecular orbitals.

Because the two nuclei are identical, symmetry requires \(c_1 = c_2 \equiv c\) (and we choose \(c > 0\)).

The \(\pm\) sign indicates that two distinct molecular orbitals can be formed:

the bonding combination (\(+\)), which enhances electron density between the nuclei

the antibonding combination (\(-\)), which decreases electron density between the nuclei

Normalization of the molecular wavefunction requires:

Overlap Integral#

We now consider the bonding molecular orbital (the “+” combination) and evaluate the normalization condition.

Here, \(S\) is the overlap integral, which depends on the internuclear distance \(R\):

Expanding the integrand:

Normalized atomic orbitals satisfy:

Defining the overlap integral:

we obtain:

Thus, the normalized bonding molecular orbital is:

Normalization of the antibonding combination yields:

Note that the antibonding orbital has a node between the nuclei, resulting in zero electron density in that region.

Bonding vs antibonding orbitals#

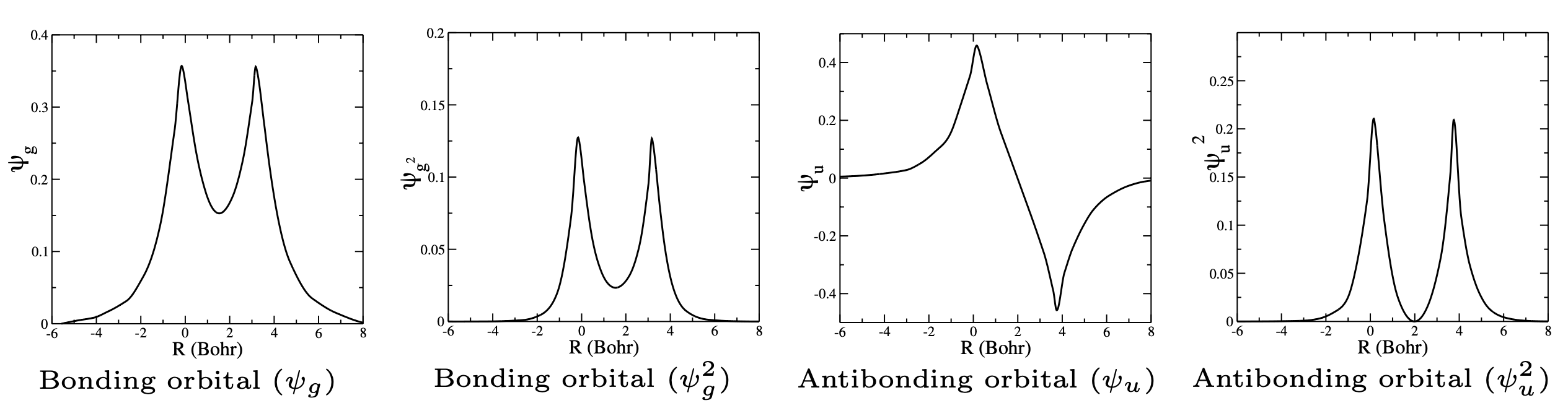

Fig. 103 Bonding vs anti-bonding wavefunctions (Molecular Orbitals). Show are wavefunctions and probability densities (squares of wavefunctions)#

The main feature of a chemical bond is the increased electron density between the nuclei. This identifies the + wavefunction as a bonding orbital and \(-\) as an antibonding orbital.

When a molecule has a center of symmetry (here at the half-way between the nuclei), the wavefunction may or may not change sign when it is inverted through the center of symmetry. If the origin is placed at the center of symmetry then we can assign symmetry labels \(g\) and \(u\) to the wavefunctions.

If \(\psi(x, y, z) = \psi(-x, -y, -z)\) then the symmetry label is \(g\) (even parity) and for \(\psi(x, y, z) = -\psi(-x, -y, -z)\) we have \(u\) label (odd parity).

According to this notation the \(g\) symmetry orbital is the bonding orbital and the \(u\) symmetry corresponds to the antibonding orbital. Later we will see that this is {reversed} for \(\pi\)-orbitals!

The overlap integral \(S(R)\) can be evaluated analytically (derivation not shown):

Note that when \(R = 0\) (i.e. the nuclei overlap), \(S(0) = 1\) (just a check to see that the expression is reasonable).

Energy of the hydrogen molecule ion#

Using a linear combination of atomic orbitals, it is possible to calculate the best values, in terms of energy, for the coefficients \(c_1\) and \(c_2\). Remember that this linear combination can only provide an approximate solution to the \(H_2^+\) Schr”odinger equation. The variational principle provides a systematic way to calculate the energy when \(R\) (the distance between the nuclei) is fixed:

where \(H_{AA}\), \(H_{AB}\), \(H_{BB}\), \(S_{AA}\), \(S_{AB}\) and \(S_{BB}\) have been used to denote the integrals occurring in variational treatment of the problem. The integrals \(H_{AA}\) and \(H_{BB}\) are called the Coulomb integrals (sometimes generally termed as matrix elements).

This interaction is attractive and therefore its numerical value must be negative. Note that by symmetry \(H_{AA} = H_{BB}\). The integral \(H_{AB}\) is called the resonance integral and also by symmetry \(H_{AB} = H_{BA}\).

Variational solution#

To minimize the energy expectation value with respect to \(c_1\) and \(c_2\), we have to calculate the partial derivatives of energy with respect to these parameters:

Both sides can be differentiated with respect to \(c_1\) to give:

In similar way, differentiation with respect to \(c_2\) gives:

At the minimum energy (for \(c_1\) and \(c_2\)), the partial derivatives must be zero:

In matrix notation this is (a generalized matrix eigenvalue problem):

From linear algebra, we know that a non-trivial solution exists only if:

Energies of bonding and antibonding#

It can be shown that \(H_{AA} = H_{BB} = E_{1s} + J(R)\), where \(E_{1s}\) is the energy of a single hydrogen atom and \(J(R)\) is a function of internuclear distance \(R\):

Furthermore, \(H_{AB} = H_{BA} = E_{1s}S(R) + K(R)\), where \(K(R)\) is also a function of \(R\):

If these expressions are substituted into the previous secular determinant, we get:

This equation has two roots:

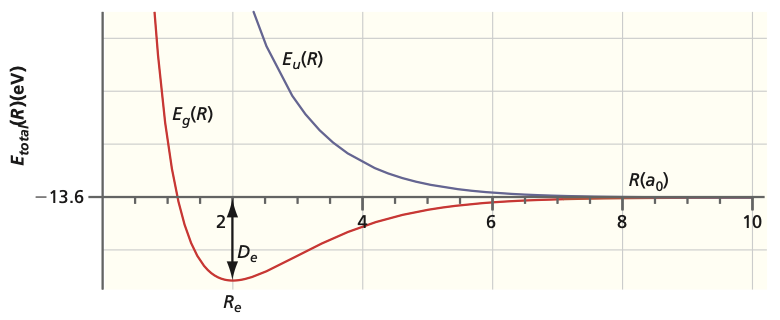

Fig. 104 Energies of bonding and antibonding orbitals#

Since energy is a relative quantity, it can be expressed relative to separated nuclei:

Comparison of MO energies with experiments#

These values can be compared with experimental results. The calculated ground state equilibrium bond length is 132 pm whereas the experimental value is 106 pm. The binding energy is 170 kJ mol \(^{-1}\) whereas the experimental value is 258 kJ \(mol^{-1}\).

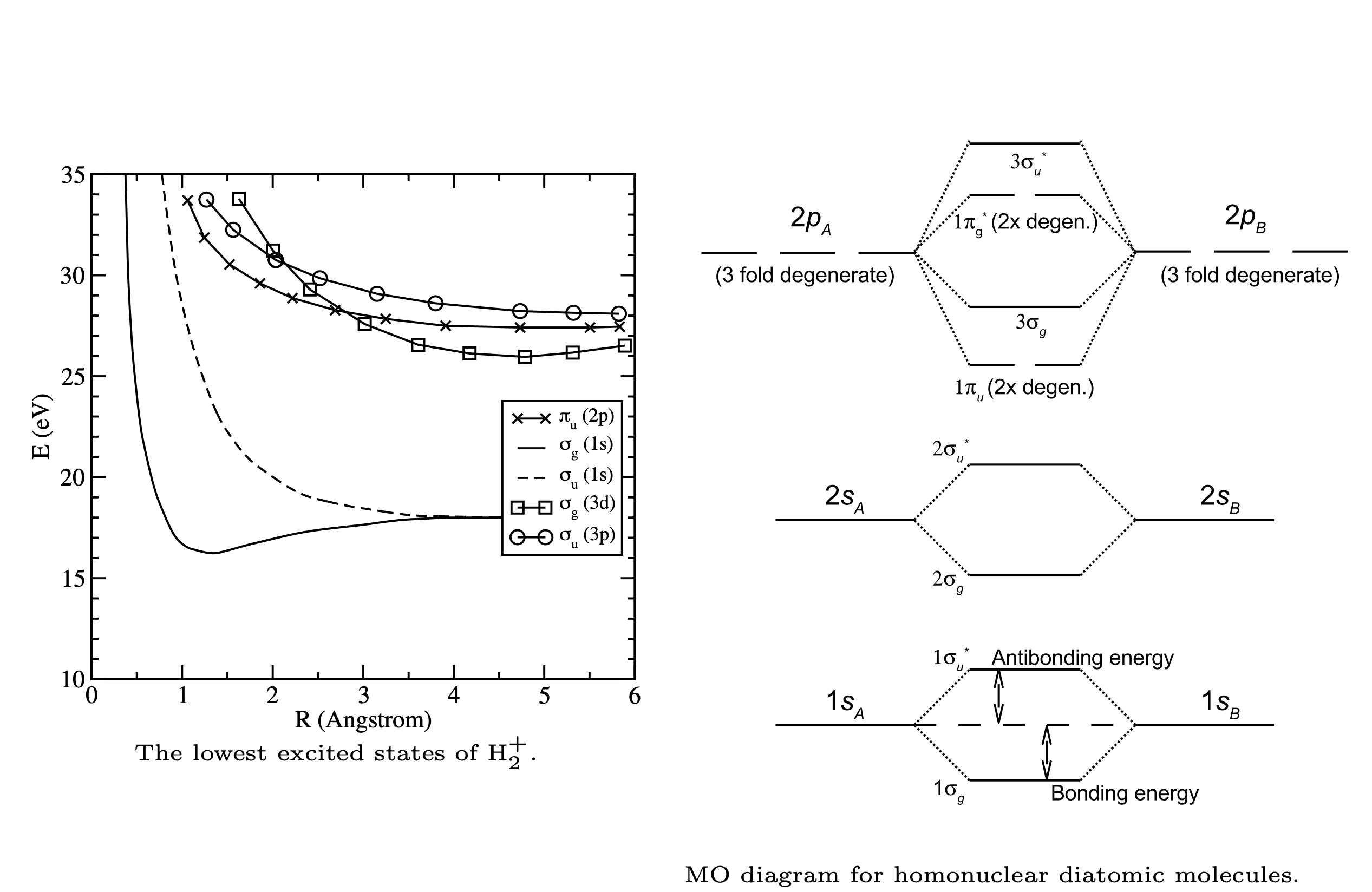

The excited state (labeled with \(u\)) leads to repulsive behavior at all bond lengths \(R\) (i.e. antibonding). Because the \(u\) state lies higher in energy than the \(g\) state, the \(u\) state is an excited state of \(H_2^+\).

This calculation can be made more accurate by adding more than two terms to the linear combination. This procedure would also yield more excited state solutions. These would correspond \(u\)/\(g\) combinations of \(2s\), \(2p_x\), \(2p_y\), \(2p_z\) etc. orbitals.

MO diagrams#

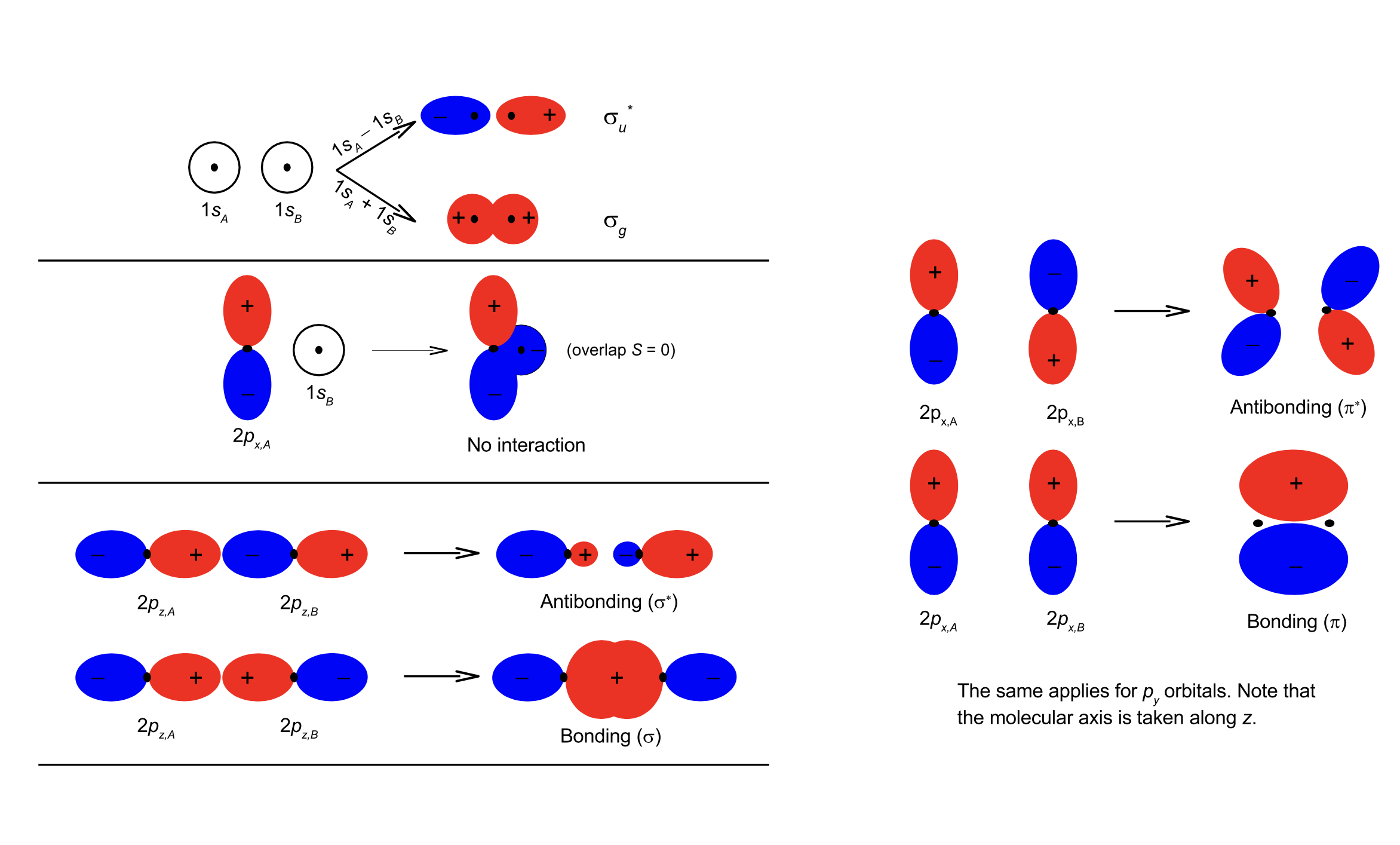

It is a common practice to represent the molecular orbitals by molecular orbital (MO) diagrams. The formation of bonding and antibonding orbitals can be visualized as follows:

Fig. 105 Molecular Orbital diagram#

\(\sigma\) orbitals When two \(s\) or \(p_z\) orbitals interact, a \(\sigma\) molecular orbital is formed. The notation \(\sigma\) specifies the amount of angular momentum about the molecular axis (for \(\sigma\), \(\lambda = 0\) with \(L_z = \pm\lambda\hbar\)). In many-electron systems, both bonding and antibonding \(\sigma\) orbitals can each hold a maximum of two electrons. Antibonding orbitals are often denoted by *.

Fig. 106 MOs for homonuclear molecules have distinct symmetry#

\(\pi\) orbitals. When two \(p_{x,y}\) orbitals interact, a \(\pi\) molecular orbital forms. \(\pi\)-orbitals are doubly degenerate: \(\pi_{+1}\) and \(\pi_{-1}\) (or alternatively \(\pi_x\) and \(\pi_y\)), where the \(+1/-1\) refer to the eigenvalue of the \(L_z\) operator (\(\lambda = \pm1\)). In many-electron systems a bonding \(\pi\)-orbital can therefore hold a maximum of 4 electrons (i.e. both \(\pi_{+1}\) and \(\pi_{-1}\) each can hold two electrons). The same holds for the antibonding \(\pi\) orbitals. Note that only the atomic orbitals of the same symmetry mix to form molecular orbitals (for example, \(p_z - p_z\), \(p_x - p_x\) and \(p_y - p_y\)). When atomic \(d\) orbitals mix to form molecular orbitals, \(\sigma (\lambda = 0)\), \(\pi (\lambda = \pm 1)\) and \(\delta (\lambda = \pm 2)\) MOs form.

Fig. 107 MO diagram of homonuclear molecules follows similiar pattern with alternating bonding and anti-bonding MOs.#

Excited state energies of \(H_2^+\) resulting from a calculation employing an extended basis set (e.g. more terms in the LCAO) are shown on the left below. The MO energy diagram, which includes the higher energy molecular orbitals, is shown on the right hand side. Note that the energy order of the MOs depends on the molecule.