Linear Algebra 1: Basics#

Vectors, what are they?#

Show code cell source

# Visualizing geometric vs abstract representations of vectors

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Basis vectors and sample vector

e1 = np.array([1, 0])

e2 = np.array([0, 1])

v = 2*e1 + 3*e2

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 5))

ax.set_xlim(-0.5, 3.5)

ax.set_ylim(-0.5, 3.5)

ax.set_aspect('equal')

# Draw basis vectors

ax.arrow(0, 0, *e1, head_width=0.1, color='gray', length_includes_head=True)

ax.arrow(0, 0, *e2, head_width=0.1, color='gray', length_includes_head=True)

ax.text(1.1, -0.2, r'$\mathbf{e_1}$', fontsize=14)

ax.text(-0.2, 1.1, r'$\mathbf{e_2}$', fontsize=14)

# Draw vector v and its components

ax.arrow(0, 0, *v, head_width=0.15, color='royalblue', length_includes_head=True)

ax.plot([0, v[0]], [v[1], v[1]], '--', color='gray')

ax.plot([v[0], v[0]], [0, v[1]], '--', color='gray')

ax.text(v[0]+0.1, v[1]/2, r'$2\mathbf{e_1}$', color='gray', fontsize=12, rotation=0)

ax.text(v[0]/2, v[1]+0.1, r'$3\mathbf{e_2}$', color='gray', fontsize=12, rotation=0)

ax.text(v[0]+0.1, v[1]+0.1, r'$\mathbf{v} = 2\mathbf{e_1} + 3\mathbf{e_2}$', color='royalblue', fontsize=14)

# Axes and labels

ax.axhline(0, color='black', lw=1)

ax.axvline(0, color='black', lw=1)

ax.set_xlabel('x-component')

ax.set_ylabel('y-component')

ax.set_title('Geometric vs Abstract Representations of a Vector', fontsize=13)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Display the abstract forms

from IPython.display import Markdown

Markdown(r"""

**Abstract Representations:**

$$

\mathbf{v} =

\begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix}

\quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad

|v\rangle = 2|e_1\rangle + 3|e_2\rangle

$$

""")

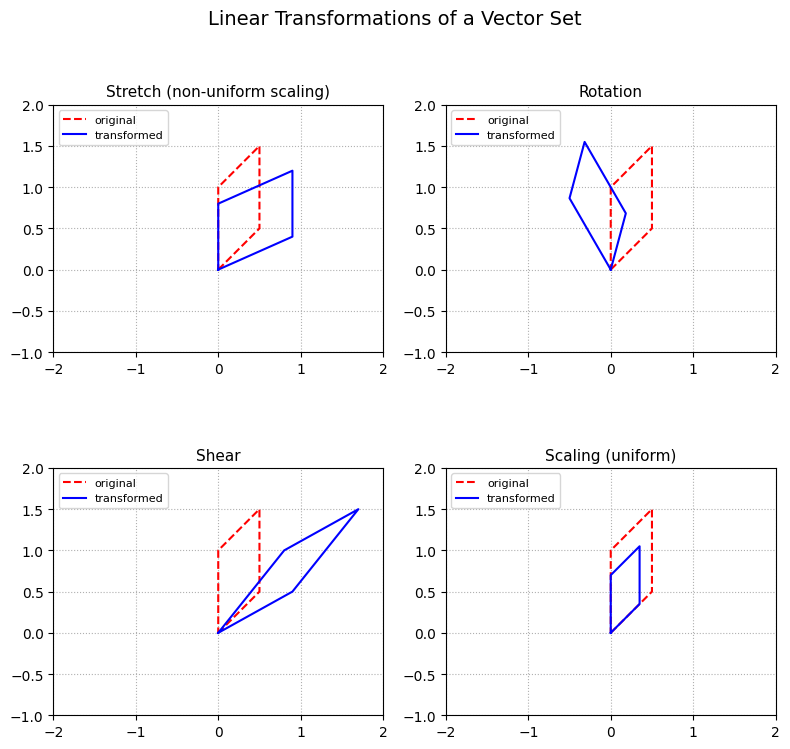

Abstract Representations:

$$ \mathbf{v} = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \ 3 \end{pmatrix} \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad |v\rangle = 2|e_1\rangle + 3|e_2\rangle $$

Vectors as Arrays of Numbers#

A vector is an ordered collection of numbers that represents the state or configuration of a physical system.

\(a = (-2, 8)\) — a 2D vector

\(e_1\) = (1,0) - a unit vector along x axis and \(e_2 = (0,1)\) a unit vector along y axis

\(b = (1.34, 4.23, 5.98)\) — a 3D vector

\(c = (1, -2, 4i, 3 + 2i)\) — a 4D vector with complex components

\(f = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, \ldots)\) — an infinite-dimensional vector (e.g., a sequence)

Note: Vectors may belong to real or complex vector spaces depending on the nature of their components.

Vector Space

Any vector in an \(N\)-dimensional space can be written as a linear combination of \(N\) linearly independent basis vectors.

For instance, in 2D space, we can choose two perpendicular unit vectors \(e_1\) and \(e_2\) to form a convenient basis:

If we choose a rotated basis \(e'_1\), \(e'_2\) (e.g choose basis vectors with length 2), the components change, but the vector itself remains the same:

Row and Column Vectors#

In linear algebra and quantum mechanics, we distinguish between column vectors (kets) and row vectors (bras), which are related by the transpose (and, in complex spaces, by the Hermitian conjugate):

Although they describe the same state or object, bras and kets “live” in dual spaces — column vectors form one space, while row vectors belong to its dual space. Their interaction through the inner product \(\langle b | a \rangle\) gives a scalar quantity.

Inner products and orthogonality#

Dot product \(\langle a\mid b \rangle\) quantifies the projection of vector \(a\) on \(b\) and vice-versa. That is, how much \(a\) and \(b\) have in common in terms of direction in space!

Dot product: geometric definition

The \(\theta\) measures angle between a and b. If vectors are perpendicular like unit vectors in cartesian system we call them orthogonal

Orthonormal vectors are both normalized and orthogonal. We denote orthornamilty condition with the convenient Kornecker symbol: \(\delta_{ij}=0\) when \(i\neq j\) and \(1\) when \(i=j\).

Norm of a vector \(\mid a\mid\) Is project of the vector onto itself and quantifies the length of the vector. When the norm is \(\mid a \mid=1\), we say that the vector is normalized.

Inner product between two vectors

Use inner product to defiine components

Decomposition of functions into orthogonal components#

Writing a vector in terms of its orthogonal unit vectors is a powerful mathematical technique which permeates much of quantum mechanics. The role of finite dimensional vectors in QM play the infinite dimensional functions. In analogy with sequence vectors which can live in 2D, 3D or ND spaces, the inifinite dimensional space of functions in quantum mathematics is known as a Hilbert space, named after famous mathematician David Hilbert. We will not go too much in depth about functional spaces other than listing some powerful analogies with simple sequence vectors.

Vectors |

Functions |

|---|---|

Orthonormality \(\\ \langle x\mid y \rangle = \sum^{i=N}_{i=1} x_i y_i=\delta_{xy}\) |

Orthonormality \(\\ \langle \phi_i \mid \phi_j \rangle = \int^{+\infty}_{-\infty} \phi_i(x) \phi_j(x)dx=\delta_{ij}\) |

Linear superposition \(\\ \mid A \rangle = A_x \mid x\rangle+A_y\mid y\rangle\) |

Linear superposition \(\\ \mid f\rangle = c_1 \mid\phi_1\rangle+c_2\mid\phi_2\rangle\) |

Projections \(\\ \langle e_x\mid A\rangle=A_x \langle x\mid x \rangle +A_y \langle x\mid y \rangle=A_x \) |

Projections \(\\ \langle \phi_1\mid \Psi\rangle=c_1 \langle \Psi \mid\phi_1 \rangle +c_2 \langle \Psi \mid\phi_2 \rangle=c_1\) |

System of Linear Equations as Matrix Operations#

A system of linear equations can be interpreted as a matrix operating on a vector to produce another vector. For example, consider the system:

This system can be written compactly in matrix form as:

A system of linear equation as matrix vector product

\(A\) is a matrix containing the coefficients of the system,

\(\mathbf{x}\) is the vector of unknowns, and

\(\mathbf{b}\) is the vector of constants (right-hand side).

For a 2D system, this becomes:

Matrix vector Multiplication#

Row by column product rule

Matrix multiplication operates by taking the dot product of the rows of the matrix \(A\) with the vector \(\mathbf{x}\). For the above example:

This shows how the system of equations is equivalent to multiplying the matrix by the vector.

Lower level definition of Matrix Multiplication

In general, if \(A\) is an \(m \times n\) matrix and \(\mathbf{x}\) is a vector of dimension \(n\), the matrix-vector multiplication \(A \mathbf{x}\) is defined as:

Where \(a_{ij}\) are the elements of matrix \(A\), and \(x_j\) are the components of vector \(\mathbf{x}\).

Solving linear equation via matrix Inversion

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

# Define the coefficients matrix A and the right-hand side vector b

print('Solving Ax=b via matrix inversion')

A = np.array([[2, 3],

[1, -2]])

b = np.array([7, 1])

print('A', A)

print('b', b)

# Calculate the inverse of matrix A

A_inv = np.linalg.inv(A)

# Solve for the unknown vector x using matrix inversion: x = A_inv * b

x = np.dot(A_inv, b)

print("Solution using matrix inversion:")

print("x =", x)

Solving Ax=b via matrix inversion

A [[ 2 3]

[ 1 -2]]

b [7 1]

Solution using matrix inversion:

x = [2.42857143 0.71428571]

Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors#

When a matrix acts on a vector, it generally changes both its direction and length. However, there are special vectors that preserve their direction—they are only scaled by the transformation. These are called eigenvectors, and the corresponding scaling factors are eigenvalues.

Definition of Eigenvalue Problem

A vector \(\mathbf{v}\) is an eigenvector of a matrix \(A\) if

where \(\lambda\) is a scalar called the eigenvalue.

In this equation:

\(A\) is the linear transformation (matrix or operator),

\(\mathbf{v}\) is a non-zero vector whose direction remains unchanged,

\(\lambda\) tells how much \(\mathbf{v}\) is stretched, compressed, or flipped.

Finding Eigenvalues#

Rearranging the equation gives:

For a nontrivial solution (\(\mathbf{v} \neq 0\)), the determinant must vanish:

This condition is the characteristic equation of the matrix and yields the possible eigenvalues \(\lambda\).

Geometric Meaning#

If \(\lambda > 1\): the vector is stretched.

If \(0 < \lambda < 1\): the vector is compressed.

If \(\lambda < 0\): the vector is flipped in direction.

If \(\lambda = 0\): the vector is collapsed to the origin.

In quantum mechanics, this idea generalizes to operators acting on wavefunctions—where eigenvalues correspond to measurable quantities (observables) and eigenvectors to the states with definite outcomes.

Property |

Expression |

Meaning |

|---|---|---|

Eigenvalue equation |

\(A\mathbf{v} = \lambda\mathbf{v}\) |

Defines scaling along eigenvector |

Inverse action |

\(A^{-1}\mathbf{v} = \frac{1}{\lambda}\mathbf{v}\) |

Inverse rescales in opposite way |

Invertibility condition |

\(\det(A) \neq 0\) or all \(\lambda \neq 0\) |

Matrix is invertible only if no eigenvalue is zero |

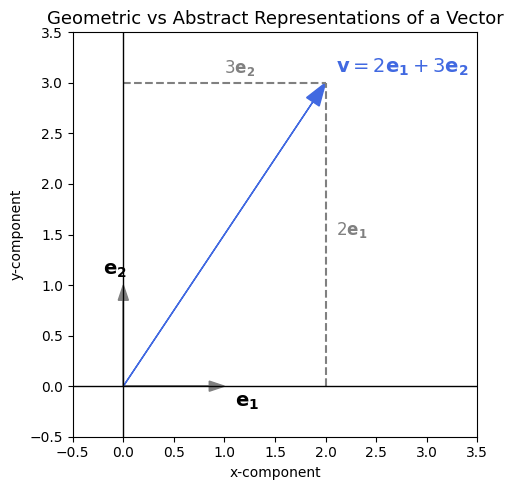

Visualizing Action of a Matrix on a Vector#

These transformations illustrate different ways of modifying vectors and geometric shapes through scaling, shearing, and identity operations. We use a 2D vector and matrices as an example.

Matrix Type |

Example |

Effect |

|---|---|---|

Diagonal, unequal entries |

|

Stretch — different scaling per axis |

Diagonal, equal entries |

|

Uniform scaling — isotropic compression |

Orthogonal (rotation matrix) |

|

Rotation — preserves lengths and angles |

Off-diagonal elements |

|

Shear — slants axes without changing area |

We pick the folloing four dummy vectors and act our matrix on all of them to see how the relationship between their distances and angles changes

We connect the points defined by this vectors to aid our visualization

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Define the original shape (unit square)

coords = np.array([

[0, 0],

[0.5, 0.5],

[0.5, 1.5],

[0, 1],

[0, 0]

]).T

# Define transformations

stretch = np.array([[1.8, 0],

[0, 0.8]]) # non-uniform diagonal → stretch

rotation = np.array([[np.cos(np.pi/6), -np.sin(np.pi/6)],

[np.sin(np.pi/6), np.cos(np.pi/6)]]) # 30° rotation

shear = np.array([[1, 0.8],

[0, 1]]) # off-diagonal term → shear

scaling = np.array([[0.7, 0],

[0, 0.7]]) # uniform diagonal → scaling

# Collect transformations

transforms = {

"Stretch (non-uniform scaling)": stretch,

"Rotation": rotation,

"Shear": shear,

"Scaling (uniform)": scaling

}

# Set up 2x2 subplots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(8, 8))

for ax, (name, M) in zip(axes.flat, transforms.items()):

# Original shape

ax.plot(coords[0], coords[1], 'r--', label='original')

# Transformed shape

new_coords = M @ coords

ax.plot(new_coords[0], new_coords[1], 'b-', label='transformed')

# Style

ax.set_title(name, fontsize=11)

ax.set_aspect('equal', 'box')

ax.set_xlim(-2, 2)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 2)

ax.grid(True, ls=':')

ax.legend(fontsize=8, loc='upper left')

plt.suptitle("Linear Transformations of a Vector Set", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()