Angular momentum#

What You Need to Know

Angular momentum is essential in both classical and quantum mechanics. In classical mechanics, all isolated systems conserve angular momentum (along with energy and linear momentum). This conservation law simplifies calculations for systems such as planetary orbits, rotations of rigid bodies, and many other dynamic systems.

In quantum mechanics, angular momentum is similarly fundamental, especially in understanding atomic structure and other systems with rotational symmetry.

Angular momentum in QM is represented by an operator—a vector operator, to be specific, much like the momentum operator.

However, unlike the linear momentum operator, the three components of the angular momentum operator do not commute.

Property |

Linear Momentum |

Angular Momentum |

|---|---|---|

Physical nature |

Motion along a straight line |

Rotation about an axis |

Vector form |

\(\vec{p} = m\vec{v}\) |

\(\vec{L} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p}\) |

Effective mass |

\(m\) |

\(I = m r^2\) |

Velocity |

\(v\) |

\(\omega=\frac{v}{r}\) |

Magnitude (scalar form) |

\(\mid\vec{p}\mid = m v\) |

\(\mid\vec{L}\mid = I \omega\) |

Kinetic energy |

\(E_k = \dfrac{p^2}{2m}\) |

\(E_\text{rot} = \dfrac{L^2}{2I}\) |

Quantum operator |

\(\hat{p}_x = -i\hbar\dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}\) |

\(\hat{L}_x = \hat{y}\hat{p}_z - \hat{z}\hat{p}_y\) |

Conservation law |

Conserved if no net external force acts |

Conserved if no net external torque acts |

Conservation condition |

\(\sum \vec{F}_\text{ext} = 0\) |

\(\sum \vec{\tau}_\text{ext} = 0\) |

veloctiy vs angular velocity

In circular motion, angular velocity (\(\omega\)) measures how fast the angle changes, while linear velocity (\(v\)) measures how fast the object moves along the circular path.

For a full rotation, the arc length traveled is related to the angle by

Differentiating with respect to time gives

or equivalently,

Thus, angular velocity is the rate of rotation per unit radius—objects farther from the axis move faster linearly for the same angular speed.

Moment of inertia

Consider a rigid body rotating about a fixed axis with angular velocity \(\omega\). Each particle \(i\) of mass \(m_i\) at distance \(r_i\) from the axis moves with linear velocity

The kinetic energy of that particle is

For the whole body, total rotational kinetic energy is the sum over all particles:

We define the term in parentheses as the moment of inertia:

Interpretation

The \(r_i^2\) factor naturally appears from the kinetic energy of rotational motion—it weights each mass element by how far it lies from the axis, determining its contribution to rotational inertia.

Conservation of momentum is due to symmetry#

Noether’s beautiful theorem

Every continuous symmetry of the laws of physics corresponds to a conserved quantity.

In quantum mechanics, this means that if a system’s Hamiltonian is unchanged (invariant) under a certain transformation (e.g time change, rotation or translation), there exists a corresponding conserved observable:

Translational symmetry → conservation of momentum

Rotational symmetry → conservation of angular momentum

Time-translation symmetry → conservation of energy

Fig. 69 Emily Noether a german mathematician who made important contirbutions to mathematics and physics. She also proved Noether’s first and second theorems, which are fundamental in mathematical physics. See more about her here#

Conservation of momenta

Linear momentum is defined as \(\vec{p} = m\vec{v}\)

From Newton’s second law,

Thus, when no external force acts on a system,

meaning linear momentum is conserved.

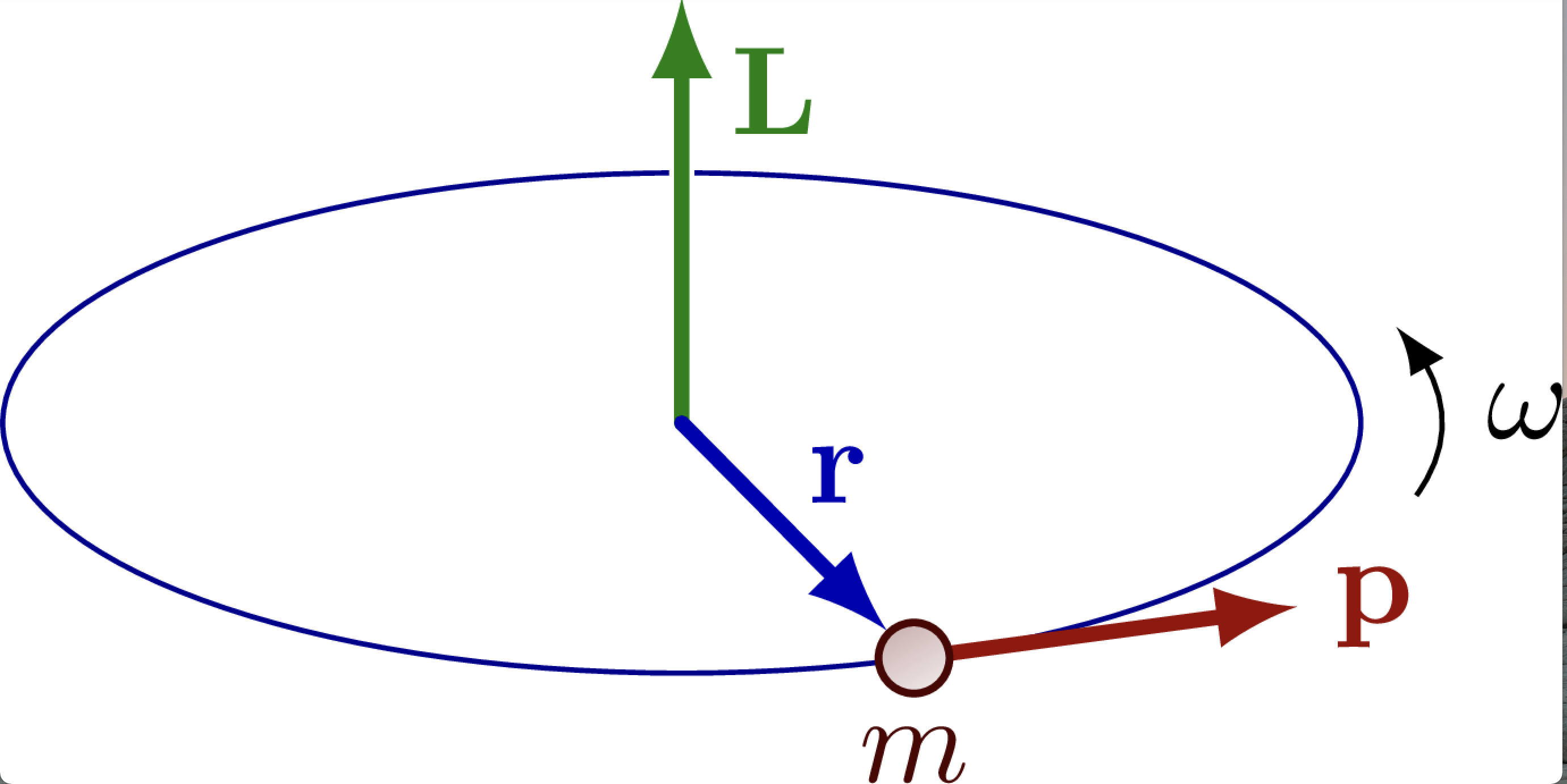

Angular momentum is defined as \(\vec{L} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p}\).

Taking the time derivative gives

\[ \frac{d\vec{L}}{dt} = \vec{r} \times \frac{d\vec{p}}{dt} = \sum \vec{\tau}_\text{ext}. \]

Therefore, when no external torque acts on the system,

so angular momentum is conserved.

Summary:

No external force → linear momentum conserved.

No external torque → angular momentum conserved.

Classical angular momentum#

Fig. 70 Angular momemntum in classical mechanics is a vector quantity defined by the cross product of position vector and linear momentum. Direction is determined by using the thumb rule.#

In classical mechanics, the angular momentum is defined via a corss product of position and linear momentum. The cross product is convenient to write using a determinant:

where \(\vec{i}, \vec{j}\) and \(\vec{k}\) denote unit vectors along the \(x, y\) and \(z\) axes. \(p_x\) and \(L_x\) are components of linear and angular momentum respectively

The Cartesian components of angular momentum

Classical picture: Rotating dumbbell#

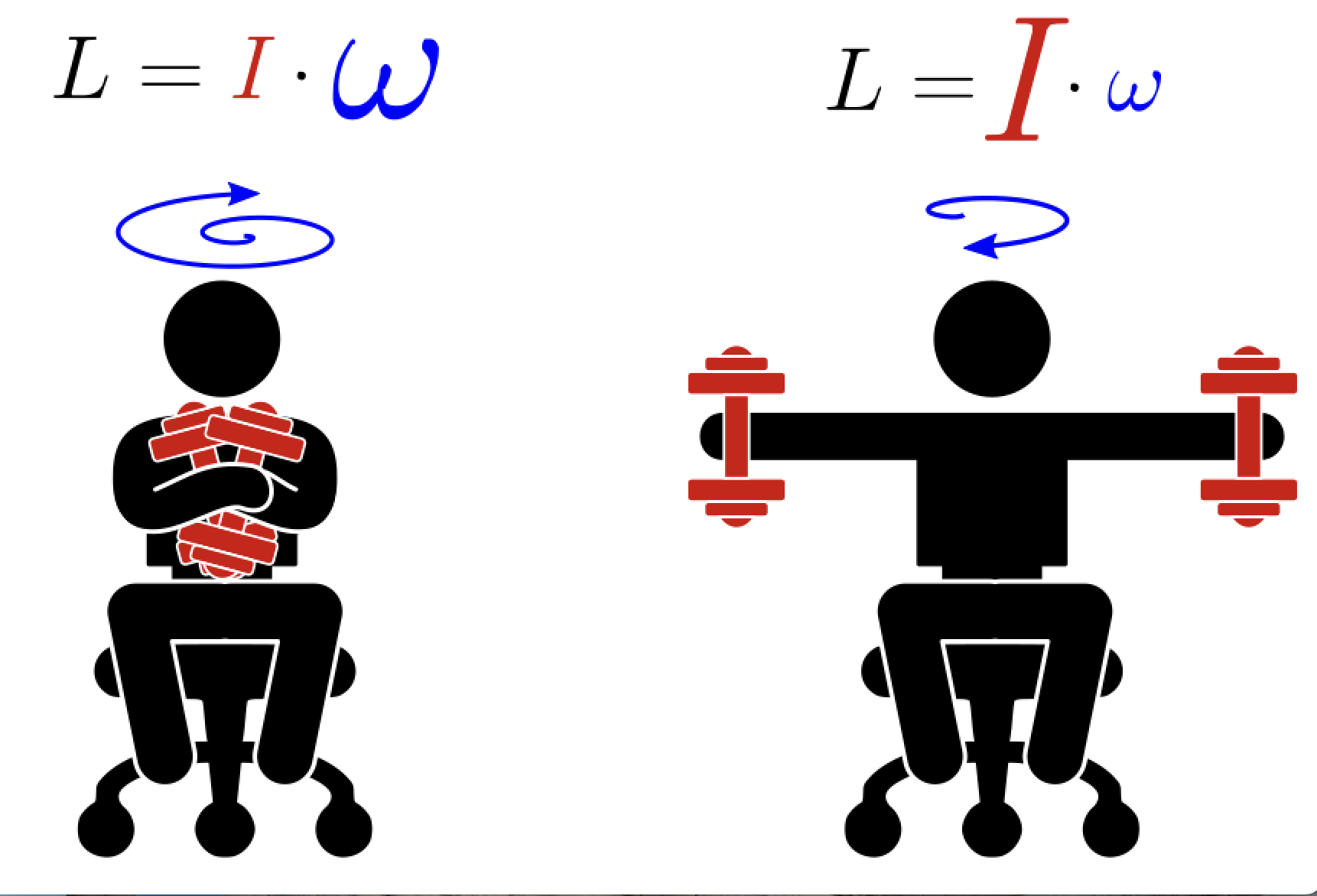

Fig. 71 Conservation of angular momentum: In the absence of torque angular momentum of conservative system remains constant. This has implications for rotational motion, for instance you can rotate faster if you decreese moment of inertia and vice versa.#

The rigid rotor is a model of a rotating dumbbell: two unequal masses held together via a rigid stick. The system is not acted upon by any external potential; hence the only energy is the kinetic energy of rotation:

Where we have plugged in \(v_1=\omega r_1\) and \(v_2=\omega_2 r\) velocities of rotation of two masses rotating with frequency \(\omega\). The classical mechanical problem of two masses is once again reducible to a single reduced mass \(\mu\) rotating around constant radius \(r=r_1+r_2\) rotating around center of mass \(m_1 r_1=m_2 r_2\).

here \(L=I \omega\) is the angular momentum, the \(I=\mu r^2\) is moment of inertia and \(\mu=\frac{m_1 m_2}{m_1+m_2}\)

Fig. 72 Angular momentum conservation#

Spherical coordinates#

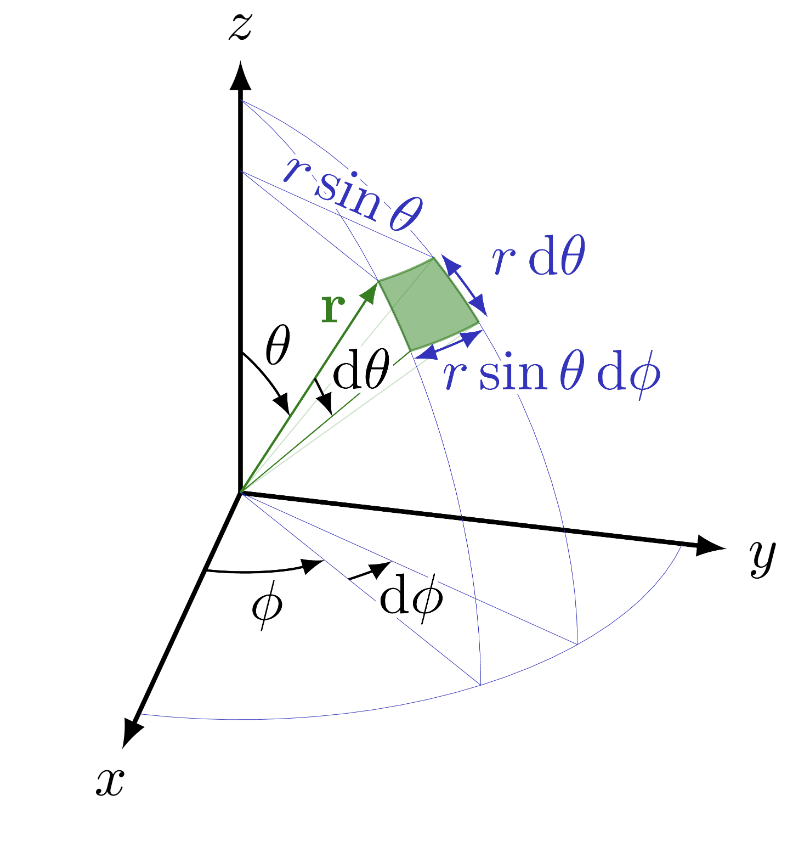

Spherical coordinates are more convenient for rotational problems where we replace \((x,y,z)\) by \((r, \phi, \theta)\).

For instance when considering rotation with fixed orbit \(r=const\) we are able to eliminate one degree of freedom associated with radial direction.

Fig. 73 Spherical coordinate system is defined by radial coordinate \(r\), azimuthal angle \(\phi\) and polar angle \(\theta\).#

Cartesian to spherical conversion

Volume Element

Laplacian

Example

Compute volume of cube and sphere using cartesian and spherical cooridnates by integrating volume elements

Solution

Example

Write down laplacian for a rigid rotor problem \(r=const\). Show what equations result when you separate the two angular variables by pluggin in \(\psi(r, \theta, \phi)\)

Solution

Quantum angular momentum#

In quantum mechanics, the classical angular momentum is replaced by the corresponding quantum mechanical operator.

In spherical coordinates, the angular momentum operators can be written in the following form. The derivations are quite tedious involving multiple applications of chain rule but its just a straightforward math procedure. Note that the choice of \(z\)-axis here was arbitrary. Sometimes the physical system implies such axis naturally (for example, the direction of an external magnetic field).

Example

Find the eigenfunctions and eigenvalues of the operator \(\hat{L}_z\):

Solution

The eigenvalue equation is:

Substituting the operator gives

Thus, the eigenfunctions of \(\hat{L}_z\) are \(e^{im\phi}\) and the corresponding eigenvalues are \(\hbar m\), where \(m\) is an integer quantum number.

Components of angular momentum do not commute!#

Unlike linear momentum components of angular momentum do not commute!

This implies that it is not possible to measure any of the Cartesian angular momentum pairs simultaneously with an infinite precision (the Heisenberg uncertainty relation).

Commutation relations of angular momentum

Note the cyclical nature of commutations between components

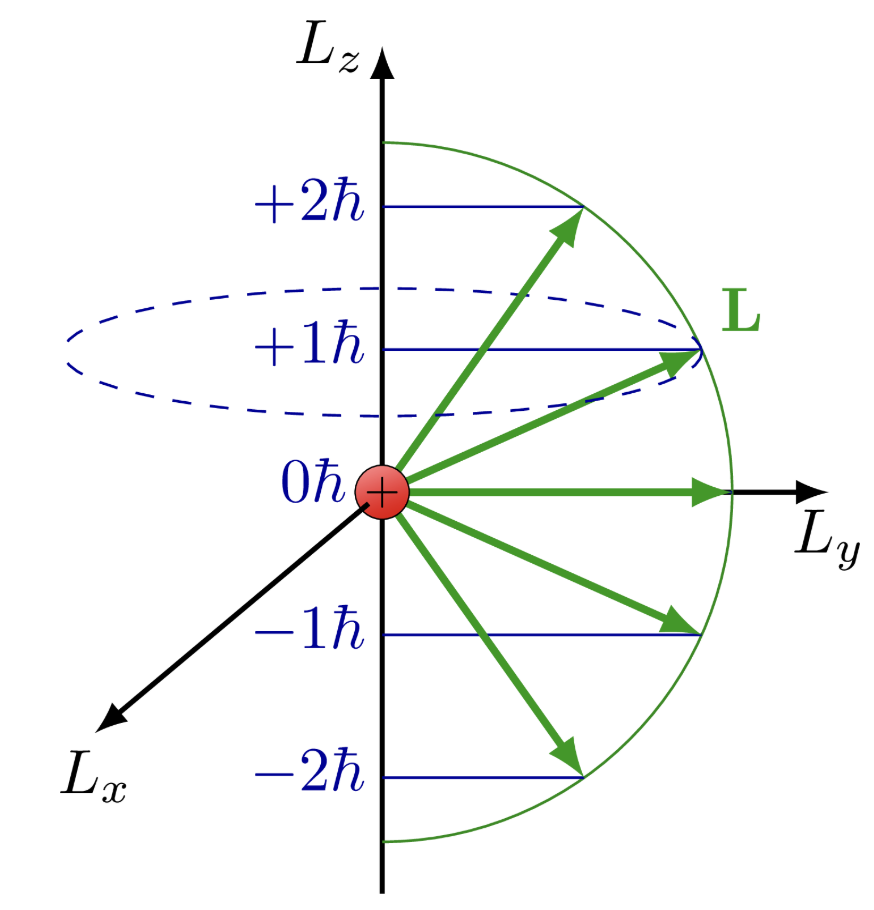

Eignefunctions and eigenvalues of \(L\) and \(L_z\)#

Since operators of component and angular momentum square commute is possible to find functions that are eigenfunctions of both \(\vec{\hat{L}}^2\) and \(\hat{L}_z\).

Eignefunctions and eigenvalues of angular momentum

Eigenfunctions: \(Y_l^m(\theta,\phi) \)

Angular quantum number: \(l = 0,1,2,...\)

Magnetic quantum number: \(|m| \leq l\) and takes \(2l+1\) integer values \((-l, ... 0, ...l)\).

Note that here \(m\) has nothing to do with magnetism but the name originates from the fact that (electron or nuclear) spins follow the same laws of angular momentum.

\(m\) describes projections of \(L\) on z axis. E.g, l=2 there are five projections \((-2, -1 ,0 1, 2)\)

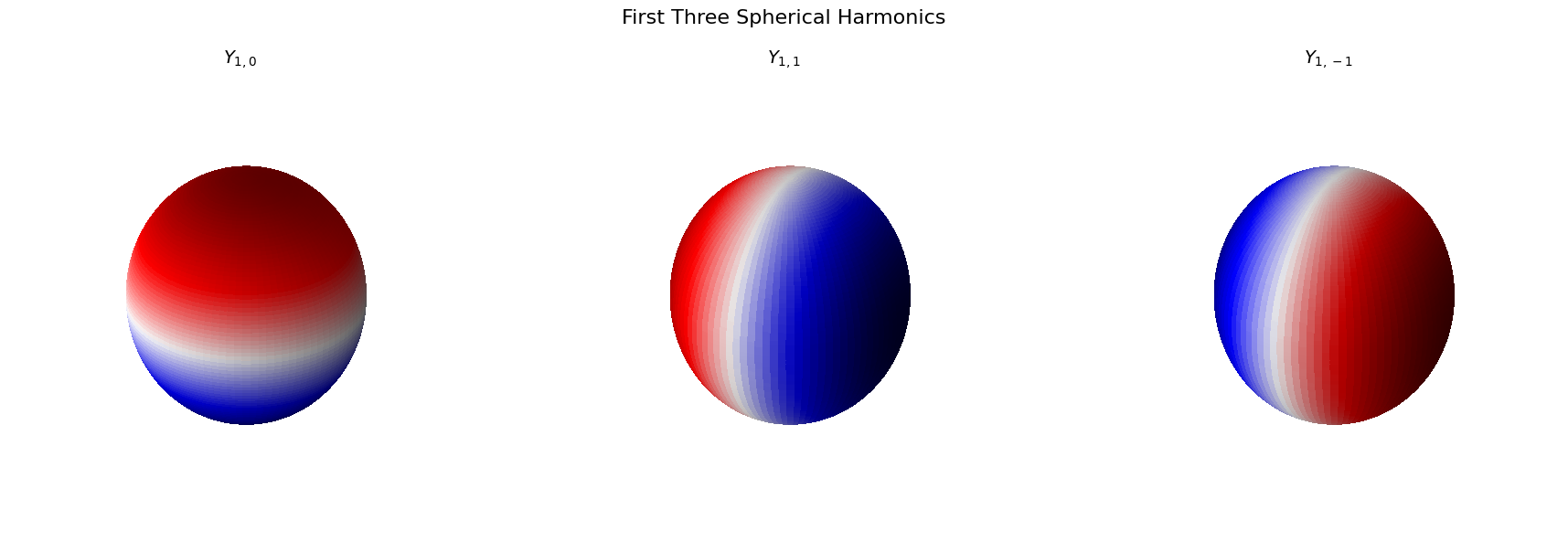

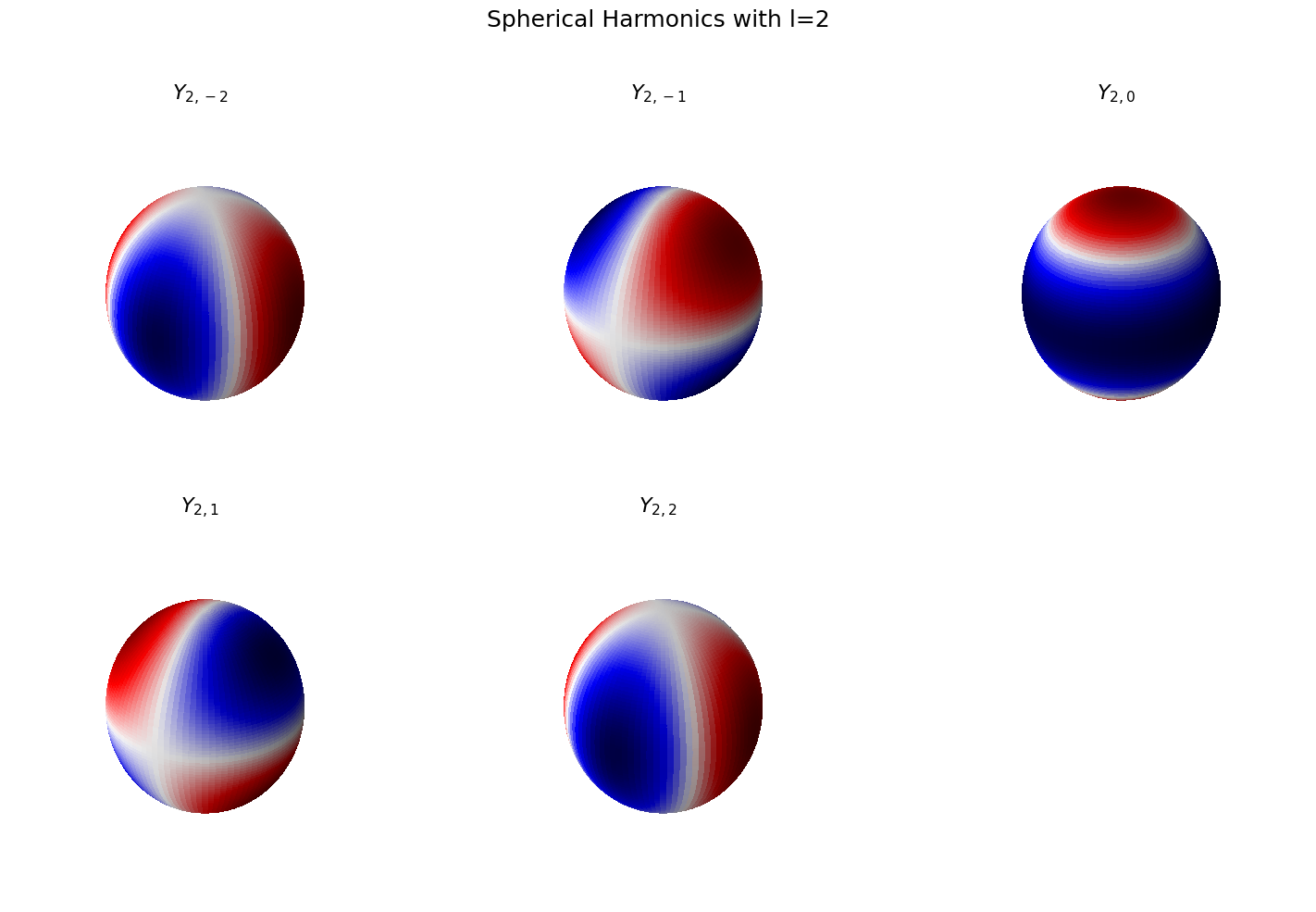

Functions \(Y_l^m\) are called spherical harmonics. Examples of spherical harmonics with various values of \(l\) and \(m\) are given below (with Condon-Shortley phase convention

Fig. 74 Angular momentum is quantized. Its magnitude can take specific values dictated by \(l\). Projections of angular momentum are also quantized and can take specific discrete values dictated by \(m\) which can take \(2l+1\) values never exceeding \(l\).#

Spherical harmonics#

Spherical harmonics, denoted as \(Y_{lm}(\theta, \phi)\) or \(|l, m\rangle\) are important in many theoretical and practical applications, e.g., the representation of multipole electrostatic and electromagnetic fields, computation of atomic orbital electron configurations, representation of gravitational fields, MRI imaging for streamline tractography, and the magnetic fields of planetary bodies and stars.

Spherical harmonics emerge from the angular part of the solutions to the Laplace equation \(\nabla^2 f=0\) in spherical coordinates which is the type of equation we obtained for Rigid Rotor problem and will see once more in Hydrogen atom problem.

\( Y_{lm}(\theta, \phi) \) |

Expression |

Colatitudinal Nodes |

Azimuthal Nodes |

|---|---|---|---|

\( Y_{00} \) |

\( \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi}} \) |

0 |

0 |

\( Y_{10} \) |

\( \sqrt{\frac{3}{4\pi}} \cos(\theta) \) |

1 (equatorial) |

0 |

\( Y_{1-1} \) |

\( \sqrt{\frac{3}{4\pi}} \sin(\theta) e^{-i\phi} \) |

0 |

1 |

\( Y_{20} \) |

\( \sqrt{\frac{5}{16\pi}} (3\cos^2(\theta) - 1) \) |

2 (colatitudinal rings) |

0 |

\( Y_{2-1} \) |

\( \sqrt{\frac{15}{4\pi}} \sin(\theta) \cos(\theta) e^{-i\phi} \) |

1 (equatorial) |

1 |

\( Y_{2-2} \) |

\( \sqrt{\frac{15}{4\pi}} \sin^2(\theta) e^{-2i\phi} \) |

0 |

2 |

Nodes of Spherical Harmonics#

The nodal structure of spherical harmonics is influenced by both the degree \( l \) and the order \(m\), defining the number and type of nodes as follows:

Colatitudinal Nodes (Polar Nodes): The variable \( \theta \) defines “polar” nodes, which appear as circular bands around the sphere. The expression in \( \cos(\theta) \) or \( \sin(\theta) \) creates colatitudinal nodes:

For example, \( Y_{10} \) with \( \cos(\theta) \) has a single node at \( \theta = \pi/2 \), creating an equatorial node.

\( Y_{20} \), with \( (3\cos^2(\theta) - 1) \), introduces two polar nodes, dividing the sphere into three regions along the colatitude.

Azimuthal Nodes (Longitudinal Nodes): The variable \( \phi \) defines “azimuthal” nodes due to the terms \(e^{im\phi}\), which create lines of longitude where the function changes phase. The number of azimuthal nodes is determined by \( |m| \):

If \( m = 0 \), there are no azimuthal nodes, as seen in \( Y_{00} \) and \( Y_{10} \).

For \( m = \pm 1 \), a single azimuthal node occurs (e.g., \( Y_{1-1} \), \( Y_{2-1} \)), and for \( m = \pm 2 \), two azimuthal nodes appear (e.g., \( Y_{2-2} \)).

Total Nodes: equal to sum of nodes coming from polar and longitudinal nodes and are exactly equal to \(l\). For instance \(l=0\) no nodes, \(l=4\) four nodes.

Orthogonality of Spherical Harmonics#

The orthogonality of spherical harmonics is expressed as:

This orthogonality condition can be explicitly written as:

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

from scipy.special import sph_harm

from scipy.integrate import dblquad

def orthogonality_test(l1, m1, l2, m2):

"""

Computes the orthogonality integral of spherical harmonics Y(l1, m1) and Y(l2, m2).

Parameters:

l1, m1 (int): Degree and order of the first spherical harmonic.

l2, m2 (int): Degree and order of the second spherical harmonic.

Returns:

float: The result of the orthogonality integral.

"""

# Define the integrand for the orthogonality condition

def integrand(theta, phi):

Y_lm1 = sph_harm(m1, l1, phi, theta)

Y_lm2 = sph_harm(m2, l2, phi, theta)

return np.real(Y_lm1 * np.conj(Y_lm2)) * np.sin(theta)

# Perform the integration over theta (0 to pi) and phi (0 to 2*pi)

integral, error = dblquad(integrand, 0, 2 * np.pi, lambda _: 0, lambda _: np.pi)

return integral

# Test orthogonality between different spherical harmonics

print("Orthogonality Tests:")

print(f"∫ Y(1,0) * Y(1,0)* = {orthogonality_test(1, 0, 1, 0):.5f} (should be close to 1)")

print(f"∫ Y(1,0) * Y(1,1)* = {orthogonality_test(1, 0, 1, 1):.5f} (should be close to 0)")

print(f"∫ Y(1,1) * Y(2,1)* = {orthogonality_test(1, 1, 2, 1):.5f} (should be close to 0)")

print(f"∫ Y(2,1) * Y(2,1)* = {orthogonality_test(2, 1, 2, 1):.5f} (should be close to 1)")

print(f"∫ Y(2,0) * Y(2,-1)* = {orthogonality_test(2, 0, 2, -1):.5f} (should be close to 0)")

Orthogonality Tests:

∫ Y(1,0) * Y(1,0)* = 1.00000 (should be close to 1)

∫ Y(1,0) * Y(1,1)* = -0.00000 (should be close to 0)

∫ Y(1,1) * Y(2,1)* = 0.00000 (should be close to 0)

∫ Y(2,1) * Y(2,1)* = 1.00000 (should be close to 1)

∫ Y(2,0) * Y(2,-1)* = 0.00000 (should be close to 0)

Plotting Spherical Harmonics#

Here we will visualize spherical harmonic on a 3D sphere of radius 1. Radidus is fixed so there are only two variables which dictate nodal features:

Colatitudinal nodes depend on \( l \) and represent bands around the sphere, arising from terms in \( \cos(\theta) \) or \( \sin(\theta) \).

Azimuthal nodes depend on \( |m| \) and create longitudinal nodes based on \( e^{im\phi} \).

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import cm

import numpy as np

from scipy.special import sph_harm

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

def generate_spherical_harmonic_data(l, m):

"""

Generates the data needed to plot the spherical harmonic for given l and m values.

Parameters:

l (int): Degree of the spherical harmonic.

m (int): Order of the spherical harmonic.

Returns:

tuple: (x, y, z, fcolors_normalized) where:

- x, y, z are the Cartesian coordinates of the spherical surface,

- fcolors_normalized is the color data for plotting.

"""

# Define theta and phi grids

phi = np.linspace(0, np.pi, 100) # colatitude

theta = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 100) # azimuth

phi, theta = np.meshgrid(phi, theta)

# Cartesian coordinates for the unit sphere

x = np.sin(phi) * np.cos(theta)

y = np.sin(phi) * np.sin(theta)

z = np.cos(phi)

# Calculate the spherical harmonic Y(l, m) and normalize it to [-1, 1] for color mapping

fcolors = sph_harm(m, l, theta, phi).real

fcolors_normalized = (fcolors - fcolors.min()) / (fcolors.max() - fcolors.min())

return x, y, z, fcolors_normalized

\(l=1\) harmonics#

Show code cell source

# Define the range of m and l values for the first three spherical harmonics

harmonics = [(0, 1), (1, 1), (-1, 1)] # List of (m, l) pairs to plot

# Create a figure to hold three subplots in one row

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(18, 6))

fig.suptitle("First Three Spherical Harmonics", fontsize=16)

for i, (m, l) in enumerate(harmonics, start=1):

x, y, z, fcolors_normalized = generate_spherical_harmonic_data(l, m)

# Create a subplot for each (m, l) pair in one row

ax = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, i, projection='3d')

ax.plot_surface(x, y, z, rstride=1, cstride=1, facecolors=cm.seismic(fcolors_normalized),

linewidth=0, antialiased=False)

# Customize each subplot

ax.set_title(f"$Y_{{{l},{m}}}$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_box_aspect([1, 1, 1]) # Ensures spherical aspect ratio

ax.set_axis_off() # Turn off axes for clarity

# Adjust layout for a clear view of all subplots in one row

plt.tight_layout(rect=[0, 0, 1, 0.95])

plt.show()

\(l=2\) harmonics#

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import cm

import numpy as np

from scipy.special import sph_harm

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

# Define l and the range of m values for spherical harmonics with l=2

l = 2

m_values = [-2, -1, 0, 1, 2]

# Create a figure to hold five subplots in a 2x3 layout

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

fig.suptitle("Spherical Harmonics with l=2", fontsize=18)

for i, m in enumerate(m_values, start=1):

# Calculate the spherical harmonic Y(l, m) and normalize it to [-1, 1] for color mapping

x, y, z, fcolors_normalized = generate_spherical_harmonic_data(l, m)

# Create a subplot for each (m, l) pair in a 2x3 grid

ax = fig.add_subplot(2, 3, i, projection='3d')

ax.plot_surface(x, y, z, rstride=1, cstride=1, facecolors=cm.seismic(fcolors_normalized),

linewidth=0, antialiased=False)

# Customize each subplot

ax.set_title(f"$Y_{{2,{m}}}$", fontsize=16)

ax.set_box_aspect([1, 1, 1]) # Ensures spherical aspect ratio

ax.set_axis_off() # Turn off axes for clarity

# Adjust layout for a clear view of all subplots in a 2x3 grid

plt.tight_layout(rect=[0, 0, 1, 0.95])

plt.show()

Total number of nodes = \(l\)#

Show code cell source

import plotly.io as pio

pio.renderers.default = "plotly_mimetype" # interactive in Jupyter-Book

import numpy as np

import plotly.graph_objects as go

from scipy.special import sph_harm

# Define the range of m and l values for the first three spherical harmonics

harmonics = [(1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3)] # List of (m, l) pairs to plot

# Initialize the figure

fig = go.Figure()

# Loop over each harmonic and create a separate subplot

for i, (m, l) in enumerate(harmonics, start=1):

# Calculate the spherical harmonic Y(l, m) and normalize it to [0, 1]

x, y, z, fcolors_normalized = generate_spherical_harmonic_data(l, m)

# Add the spherical harmonic to the figure as a surface in a new scene

fig.add_trace(go.Surface(

x=x, y=y, z=z,

surfacecolor=fcolors_normalized,

colorscale='rdbu',

showscale=False,

name=f"Y_{{{l},{m}}}",

scene=f'scene{i}' # Assign each plot to a different scene

))

# Update layout to arrange scenes in a row and add titles as annotations

fig.update_layout(

title="Three Spherical Harmonics: m=1, l=1, 2, 3",

scene=dict(domain=dict(x=[0, 0.33]), xaxis=dict(visible=False), yaxis=dict(visible=False), zaxis=dict(visible=False), aspectmode='cube'),

scene2=dict(domain=dict(x=[0.33, 0.66]), xaxis=dict(visible=False), yaxis=dict(visible=False), zaxis=dict(visible=False), aspectmode='cube'),

scene3=dict(domain=dict(x=[0.66, 1]), xaxis=dict(visible=False), yaxis=dict(visible=False), zaxis=dict(visible=False), aspectmode='cube'),

annotations=[

dict(text="Y_{2,0}", x=0.16, y=1.05, showarrow=False, xref="paper", yref="paper", font=dict(size=14)),

dict(text="Y_{2,1}", x=0.5, y=1.05, showarrow=False, xref="paper", yref="paper", font=dict(size=14)),

dict(text="Y_{2,-1}", x=0.83, y=1.05, showarrow=False, xref="paper", yref="paper", font=dict(size=14))

]

)

# Display the figure

fig.show()

Alternative visualizations of Spherical Harmonics#

Before we visualized spherical harmonics on unit sphere \(|r|=1\). However there are times where we want to visualize how magnitude of spherical harmooc is changing in space.

For instnace to visualize \(Y_{1,-1}\sim cos(\theta)\) we could either plot its values on a unit sphere or we could also plot how \(\cos(\theta)\) changes as we move around in space.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import plotly.graph_objects as go

from plotly.subplots import make_subplots

from scipy.special import sph_harm

# Set up the subplots with two side-by-side 3D plots

fig = make_subplots(rows=1, cols=2, specs=[[{'is_3d': True}, {'is_3d': True}]])

# Define theta and phi grids for spherical coordinates

theta = np.linspace(0, np.pi, 100)

phi = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 100)

theta, phi = np.meshgrid(theta, phi)

# Convert spherical to Cartesian coordinates for the surface plots

x = np.sin(theta) * np.cos(phi)

y = np.sin(theta) * np.sin(phi)

z = np.cos(theta)

# Compute the spherical harmonic Y_{1,-1}

m, l = -1, 1

r0a = np.sqrt(3 / (4 * np.pi)) * y # Y_{1,-1} harmonic on y-axis

r0 = np.abs(r0a) # Absolute value for magnitude scaling

# First plot: Scaled by the spherical harmonic (bead-like structure)

fig.add_trace(

go.Surface(

x=r0 * x, y=r0 * y, z=r0 * z, # Scale coordinates by |Y_{1,-1}|

surfacecolor=r0a, # Color by Y_{1,-1} values

colorscale='RdBu'

),

row=1, col=1

)

# Second plot: Standard unit sphere with grayscale color

fig.add_trace(

go.Surface(

x=x, y=y, z=z, # Unit sphere without scaling

surfacecolor=z, # Color by z-coordinate for simplicity

colorscale='RdBu'

),

row=1, col=2

)

# Update layout for both plots

fig.update_layout(

font_family="JuliaMono",

showlegend=False,

margin=dict(l=0, r=0, b=0, t=0),

paper_bgcolor='rgba(0,0,0,0)',

)

# Set scene properties with adjusted axis limits for each plot

fig.update_scenes(

dict(

xaxis=dict(nticks=4, range=[-0.5, 0.5]), # Limit range to reduce empty space

yaxis=dict(nticks=4, range=[-0.5, 0.5]),

zaxis=dict(nticks=4, range=[-0.5, 0.5]),

aspectratio=dict(x=1, y=1, z=1)

),

row=1, col=1

)

fig.update_scenes(

dict(

xaxis=dict(nticks=4, range=[-1.8, 1.8]),

yaxis=dict(nticks=4, range=[-1.8, 1.8]),

zaxis=dict(nticks=4, range=[-1.8, 1.8]),

aspectratio=dict(x=1, y=1, z=1)

),

row=1, col=2

)

# Hide color scales for a cleaner look

fig.update_traces(showscale=False)

# Show the plot

fig.show()

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import plotly.graph_objects as go

from plotly.subplots import make_subplots

from matplotlib import cm

import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define theta (angle) values

theta = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 100)

# Compute spherical harmonic values (scaled sin(theta) for two-lobe structure)

Y_1m1_values = np.sin(theta) # Y_{1,-1} varies with sin(theta) for the two-lobe shape

r_values = np.abs(Y_1m1_values) # Radial scaling based on |Y_{1,-1}|

# Set up the color map

cmap = matplotlib.colormaps["RdBu"]

norm = plt.Normalize(vmin=-1, vmax=1)

# Create subplots for two polar plots

fig = make_subplots(rows=1, cols=2, specs=[[{'type': 'polar'}, {'type': 'polar'}]])

# First polar plot: Two-lobed structure with color gradient

for i in range(len(theta) - 1):

fig.add_trace(

go.Scatterpolar(

r=[r_values[i], r_values[i + 1]],

theta=[np.degrees(theta[i]), np.degrees(theta[i + 1])],

mode="lines",

line=dict(color=f"rgba{cmap(norm(Y_1m1_values[i]))}", width=5),

showlegend=False

),

row=1, col=1

)

# Second polar plot: Unit circle with consistent color gradient

for i in range(len(theta) - 1):

fig.add_trace(

go.Scatterpolar(

r=[1, 1], # Fixed radius for unit circle

theta=[np.degrees(theta[i]), np.degrees(theta[i + 1])],

mode="lines",

line=dict(color=f"rgba{cmap(norm(Y_1m1_values[i]))}", width=5),

showlegend=False

),

row=1, col=2

)

# Update layout for both polar plots with fixed radius range and equal appearance

fig.update_layout(

font_family="JuliaMono",

showlegend=False,

margin=dict(l=0, r=0, b=0, t=0),

polar=dict(radialaxis=dict(range=[0, 1.2])), # First plot axis range

polar2=dict(radialaxis=dict(range=[0, 1.2])) # Second plot axis range

)

# Show the plot

fig.show()