Multi-electron atoms#

What you need to know

We approximate many-electron wavefunctions using hydrogenic orbitals as building blocks.

Unlike the hydrogen atom, multi-electron problems do not separate and therefore do not admit exact analytical solutions.

Spin and antisymmetry impose strict constraints on allowed electronic wavefunctions.

Orbital Approximation#

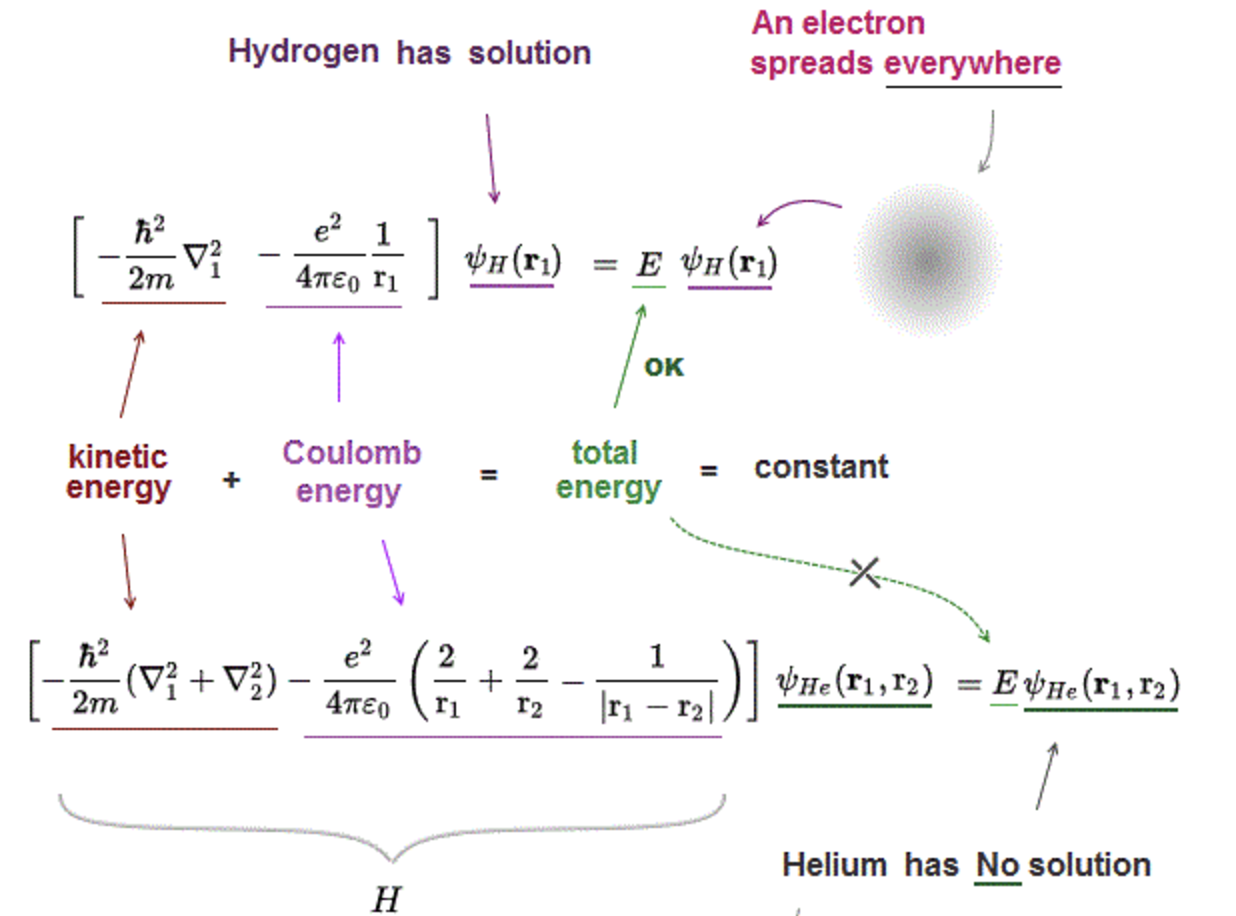

Fig. 90 Difference between the hydrogen and helium Hamiltonians that makes multi-electron atoms analytically unsolvable.#

For multi-electron atoms, the Hamiltonian depends on the coordinates of all electrons. The coordinates cannot be separated, so the Schrödinger equation is not analytically solvable.

A practical approximation is to represent the wavefunction as a product of single-electron orbitals:

These orbitals are obtained computationally (e.g., variationally).

Orbital Approximation

\(\Psi\) is the multi-electron wavefunction.

Each \(\phi_i(r)\) is an atomic orbital occupied by one electron.

Helium Wavefunction#

For helium, the simplest guess would be

This form, however, suffers from three fundamental issues:

Indistinguishability Electrons are identical; the wavefunction cannot assign “electron 1” to “orbital 1” and “electron 2” to “orbital 2.”

Missing spin information The spatial wavefunction must combine with a spin function so that the total wavefunction is antisymmetric.

Neglect of electron–electron correlation The product form assumes electrons move independently, which leads to quantitative errors in energies.

Issue 1: Indistinguishability and Antisymmetry#

Particles such as electrons are indistinguishable. Therefore the probability density must remain unchanged upon interchange:

which implies

Electrons are fermions, and Pauli’s principle dictates that their total wavefunction must be antisymmetric:

Antisymmetry Requirement

A simple way to generate symmetric/antisymmetric forms for a two-variable function \(f(x,y)\):

Symmetric:

\[ g_+(x,y) = f(x,y) + f(y,x) \]Antisymmetric:

\[ g_-(x,y) = f(x,y) - f(y,x) \]

For helium, the antisymmetrized spatial wavefunction is

Issue 2: Spin Requirement#

Electrons have two spin states, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). The total wavefunction (spatial × spin) must be antisymmetric:

If spatial part is symmetric, spin part must be antisymmetric.

If spatial part is antisymmetric, spin part must be symmetric.

Symmetric spin part:

\[ \alpha(1)\alpha(2) \]\[ \beta(1)\beta(2) \]\[ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\alpha(1)\beta(2) + \alpha(2)\beta(1)\right] \]Antisymmetric spin part:

\[ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\alpha(1)\beta(2) - \alpha(2)\beta(1)\right] \]

Pauli Exclusion Principle#

A key result of antisymmetry is the Pauli Exclusion Principle:

No two electrons can possess identical sets of quantum numbers.

For helium’s ground state (\(1s^2\)), the properly antisymmetrized total wavefunction is

Slater Determinants#

Slater introduced a compact and universally applicable way to construct antisymmetric many-electron wavefunctions:

A determinant expands into an antisymmetric sum of products of one-electron spin-orbitals

Any exchange of two electrons flips the sign of the wavefunction

This guarantees the Pauli exclusion principle is satisfied automatically

Slater Determinant

\(\chi_j(i)\) is a spin-orbital, i.e., orbital × spin function, describing electron i) in spin-orbital \(j\)

The factor \(1/\sqrt{n!}\) ensures proper normalization of the determinant

For example helium ground state Slater determinant looks like this

For Lithium ground state Slater determinant looks like this

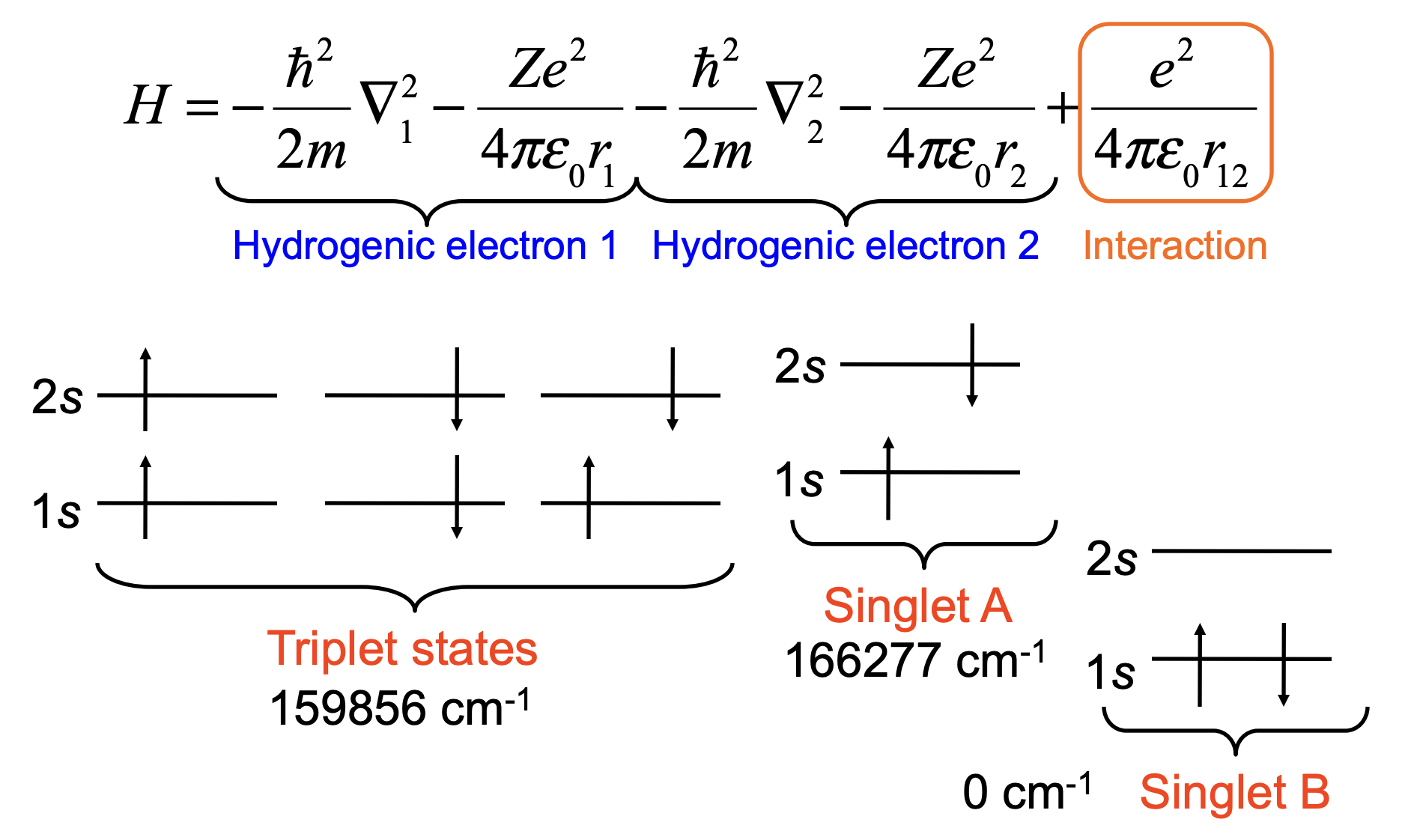

Singlet and Triplet Excited States of Helium#

When one electron occupies (1s) and the other (2s), their spatial wavefunctions can be combined as:

Spatial states

Because electrons are fermions, the total wavefunction must be antisymmetric:

The total two-electron wavefunction must be antisymmetric:

Triplet states (\(S=1\) and symmetric spin)#

Must pair with the antisymmetric spatial part \(\Psi_A(1,2)\).

Spin functions:

Total wavefunctions:

Singlet state (\(S=0\), antisymmetric spin)#

Must pair with the symmetric spatial part \(\Psi_S(1,2)\).

Spin function:

Total wavefunction:

Action of Spin Operators#

Triplets:

Singlet:

Which is lower in energy?#

Triplet has electrons spatially antisymmetric → they avoid each other → less Coulomb repulsion → lower energy

Singlet is spatially symmetric → electrons more overlapping → higher energy

This is the origin of exchange stabilization.

Energies of Multi-Electron States#

The Hamiltonian is

with \(\hat{H}_{12}\) corresponding to electron–electron repulsion.

Useful Integrals#

Single-electron energy

Coulomb Integral

always positive.

Exchange Integral

Positive, but leads to energy lowering for triplet states.

Energies of \(1s2s\) Singlet and Triplet#

Triplet (antisymmetric spatial):

Singlet (symmetric spatial):

Thus the triplet state is lower in energy due to exchange stabilization.

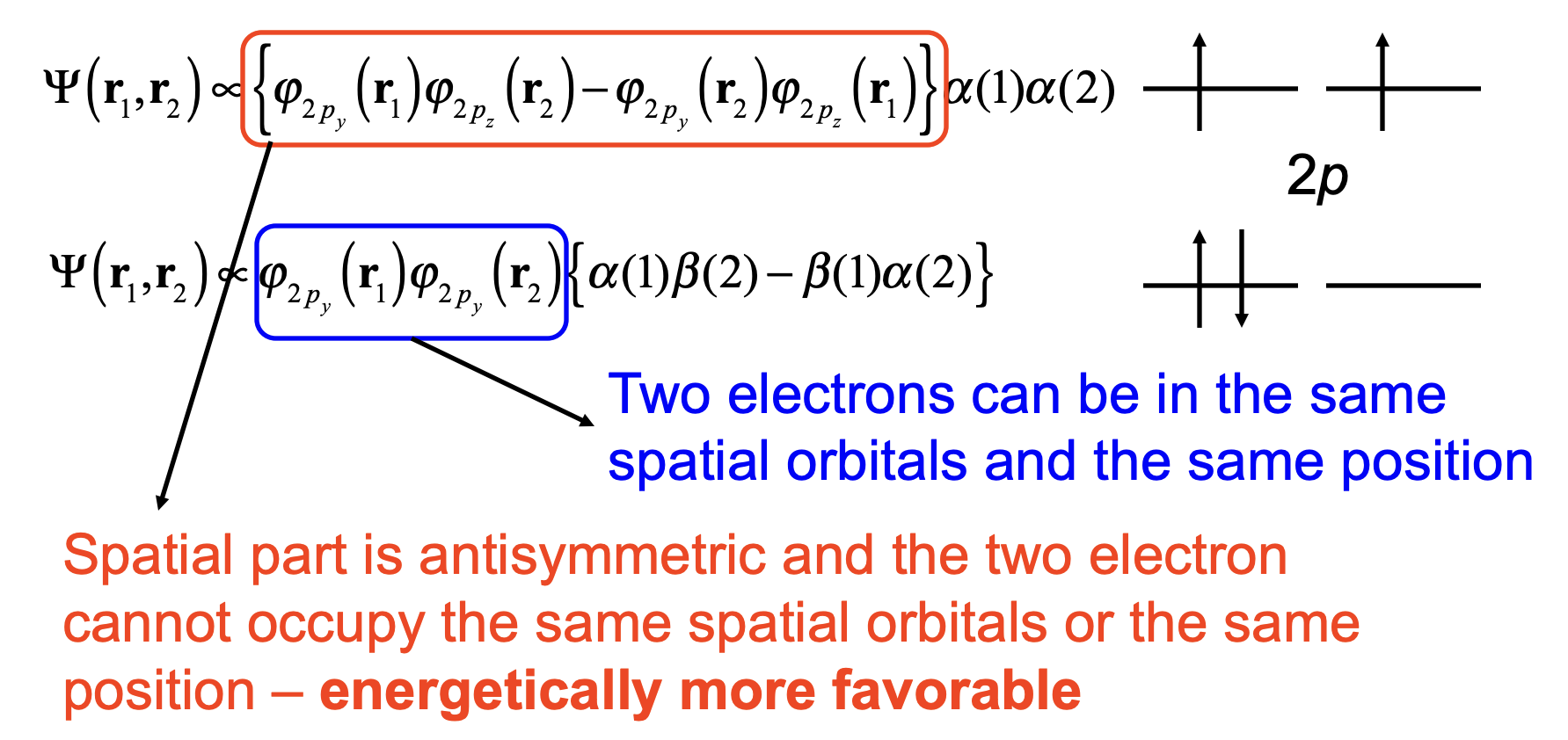

Hund’s Rule and the Aufbau Principle#

Fig. 91 Aufbau filling pattern for atomic orbitals.#

Aufbau Principle#

Electrons fill orbitals in order of increasing energy.

Pauli Exclusion Principle#

Each orbital holds at most two electrons with opposite spins.

Hund’s Rule#

Electrons occupy degenerate orbitals singly with parallel spins before pairing. This reflects exchange stabilization.

Fig. 92 Exchange stabilization in the triplet state underlies Hund’s rule.#