Wave equation#

What you need to know

Wave Equation Overview: The wave equation, a partial differential equation (PDE), fully describes the spatial and temporal evolution of waves.

Linearity of the Wave Equation: The wave equation is linear, meaning that any linear combination of solutions is also a solution. This allows the most general solution to be expressed as a linear combination of all possible solutions.

Boundary and Initial Conditions: To solve the wave equation for a specific physical system, boundary conditions must be specified. These include the values the wave function takes at the physical boundaries (e.g.,

Solution Method for 1D Guitar String: For a 1D guitar string, the wave equation is solved by separating variables, solving the resulting ordinary differential equations, and then applying boundary conditions at the two ends of the string.

Periodic Solutions: The solution for a 1D guitar string results in an infinite number of periodic solutions, which are parameterized by an integer

Classical Wave equation#

Wave equation is an example of a second order PDE (partial differential equation). This PDE governs behavior of displacement

Fig. 40 Classical wave equation can describe any complicated wave in space and time given the intitial conditions.#

Applications of the Classical Wave Equation: To illustrate the applications of the classical wave equation, we will solve it for a 1D guitar string. This provides a comprehensive mathematical description of the string’s behavior.

Predicting Evolution: By specifying arbitrary initial conditions, the wave equation allows us to precisely predict the evolution of the string over time and space.

Fig. 41 Classical wave equation can describe any complicated wave in space and time given the intitial conditions.#

Solving Wave Equation: The big picture#

Boundary Conditions: To solve the wave equation for a specific physical situation, such as a guitar string fixed at both ends, we need to specify two boundary conditions. Mathematically, these are:

where

Separation of Variables: A common method to solve such equations is the technique of separation of variables. This technique assumes that

Principle of superposition: The wave equation is linear which you can see by

Step 1: Plug the Product of Univariate Functions into the Wave Equation#

Start with the 1D wave equation that can describe 1D guitar string:

Substitute

After rearranging, we get:

Thus, we obtain two separate ordinary differential equations (ODEs) from the original partial differential equation (PDE):

where

Step 2: Solving Each Ordinary Differential Equation#

After decomposing the PDE into ODEs, we solve each ODE separately:

Solving the spatial part: when

If

Applying the boundary conditions

This implies that the string does not move—no music!

Solving the spatial part: when

If

Using Euler’s formula, this can be rewritten as:

Simplifying further:

Let

Applying the boundary conditions

At

At

For a non-trivial solution,

Hence:

Thus:

Solving temporal part

Having identified

Substitute

The solution is:

where

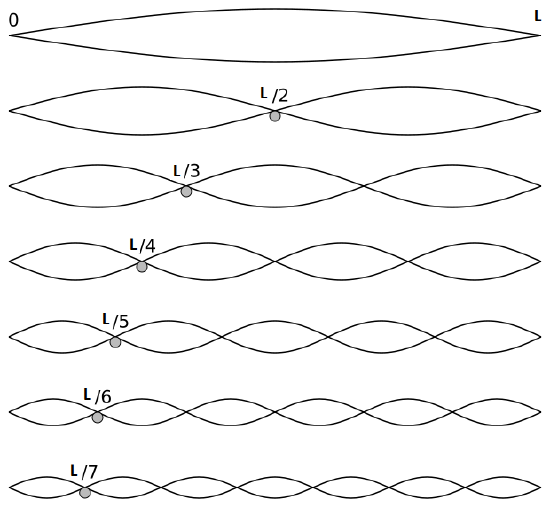

Solution for spatial part#

Becasue of boundary conditions (

Fig. 42 The first seven solutions (normal modes) of spatial part of the wave equation on a length

Solution for temporal part#

For temporal part since we do not have boundary conditions! Time is allowed to march forward into infinity. We find solution in the form of linear combination of sine and cosine functions with

In the second line we esing trig identity to express sum of cosine and sine in terms of cosine. Still we have two constantst o determine

The constants

Step 3 Full solution: A linear combination of normal modes#

After solving ODEs for spatial and tempoeral parts we now combine them into a full solution.

The complete description of any vibrational motion of the guitar string is given by the sum of the normal modes,

While the terms involving time,

Fig. 43 Presented are first six solutions from

For

For

For

Note that the general solution to wave equation is expressed as a linear combination of all normal modes

2D Membrane Vibrations#

The wave function of a 2D membrane with fixed edges depends on two independent spatial variables,

For the spatial components

The 2D normal mode is the product of two 1D mode. Since dimensions are independent we get integer numbers

The angular frequency

Where:

Fig. 44 Vibrations of 2D membrane.#

Full derivation of 2D rectangular membrane problem

To extend the solution of the 1D guitar string problem to 2D, you can analyze a 2D vibrating membrane, such as a rectangular or circular drumhead. Here’s a step-by-step solution for a 2D rectangular membrane:

Solution for a 2D Rectangular Membrane

Consider a rectangular membrane with dimensions

where

Separation of Variables

Assume the solution can be written as a product of functions, each depending on only one variable:

Substitute this into the wave equation:

This simplifies to:

Divide through by

Since the left side depends only on

Solving for

The ODE for

This has the general solution:

where

Solving for

To solve the spatial part, we need to separate the problem into two parts:

Assume:

where

So, we have:

Boundary Conditions:

For a rectangular membrane with boundaries

The solutions for (X(x)) and (Y(y)) are:

where (n) and (m) are positive integers, and:

So, the general solution for (u(x, y, t)) is:

where:

This solution describes the vibration modes of a 2D rectangular membrane, with each mode characterized by different integer values of (n) and (m).

The sound of music.#

Music produced by musical instruments is a combination of sound waves with frequencies corresponding to a superposition of normal modes (in music they call harmonics, overtones) of those musical instruments.

Learn more from this series.

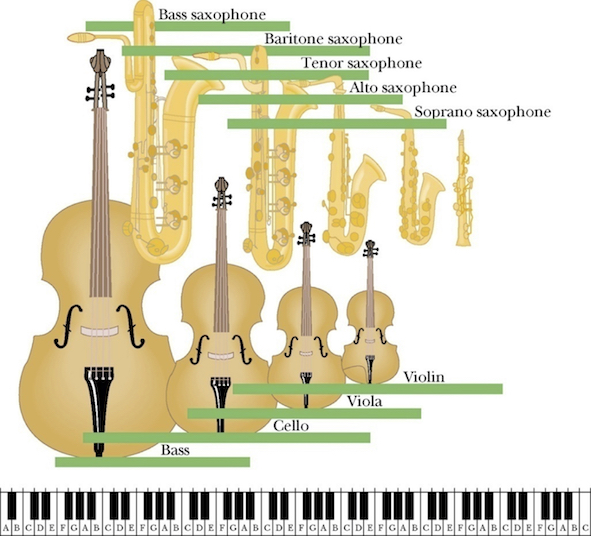

Fig. 45 The size of the musical instrument reflects the range of frequencies over which the instrument is designed to function. Smaller size implies higher frequencies, larger size implies lower frequencies.#

Example Problems#

Problem 1: Simple Harmonic Oscillator#

Solve the ODE:

where

Solution:

The characteristic equation is:

Solving for

Thus, the general solution is:

where

Problem 2: Damped Oscillator#

Solve the ODE:

where

Solution:

The characteristic equation is:

Solving for

Depending on the discriminant

Underdamping (

where

Critical Damping (

Overdamping (

where

Problem 3: ODE with Constant Coefficients#

Solve the ODE:

Solution:

The characteristic equation for this ODE is:

Solving for

Thus, the general solution is:

where

Problem 4: Simple 2nd order ODE#

Solve the ODE:

Solution:

The characteristic equation for this ODE is:

Solving for

Thus, the general solution is:

where

Problem 5: When ODE gives repeated roots#

Solve the ODE:

Solution:

The characteristic equation for this ODE is:

Factoring:

Thus:

The general solution for repeated roots is:

where