Complex numbers#

What you need to know

Complex numbers generalize oridnary 1D numbers to 2D To descirbe complex numbers we need two compoenents called real and imaginary parts. Complex numbers appear naturally in quantum mechanics and are essential part of physics.

The imaginary unit: \(i = \sqrt{-1}\) This symbol, \(i\), represents the imaginary component of a complex number, where \(i^2 = -1\).

Complex numbers as roots of polynomial equations. For example, quadratic equations can have two complex roots, showcasing their relevance in solving equations.

Cartesian and polar representations Complex numbers can be expressed in Cartesian form \((x + iy)\) or polar form \((re^{i\phi})\), where \(r\) is the magnitude, and \(\phi\) is the phase (angle).

Euler’s formula: A beautiful and fundamental equation \(re^{i\phi} = r(\cos \phi + i\sin \phi)\), elegantly connects complex numbers to trigonometric functions. uler’s equation makes it much easier to manipulate complex numbers, especially in their polar form, simplifying multiplication and division.

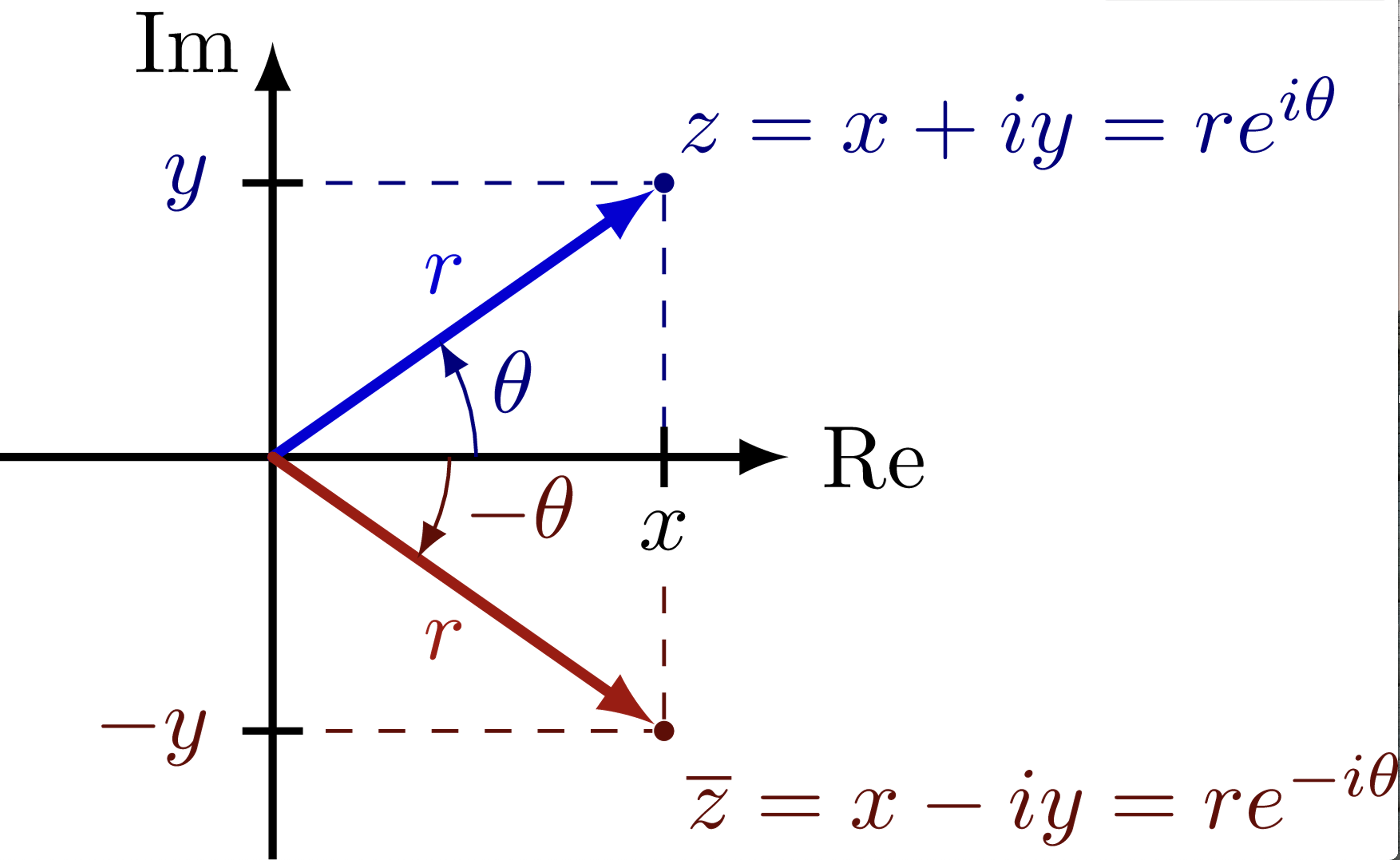

Rotation in the complex plane Multiplying by a complex number in polar form corresponds to a rotation. For instance, \(re^{i\phi}\) rotates a vector of length \(r\) counterclockwise by an angle \(\phi\), while \(re^{-i\phi}\) rotates it clockwise by \(\phi\).

Complex conjugate: Flipping the imaginary part The conjugate of a complex number \(z = x + iy\) is given by \(z^* = x - iy\).

Multiplying by the conjugate When you multiply a complex number by its conjugate, \(z \cdot z^*\), the result is a real number equal to the square of its distance from the origin in the complex plane: \(|z|^2 = x^2 + y^2\).

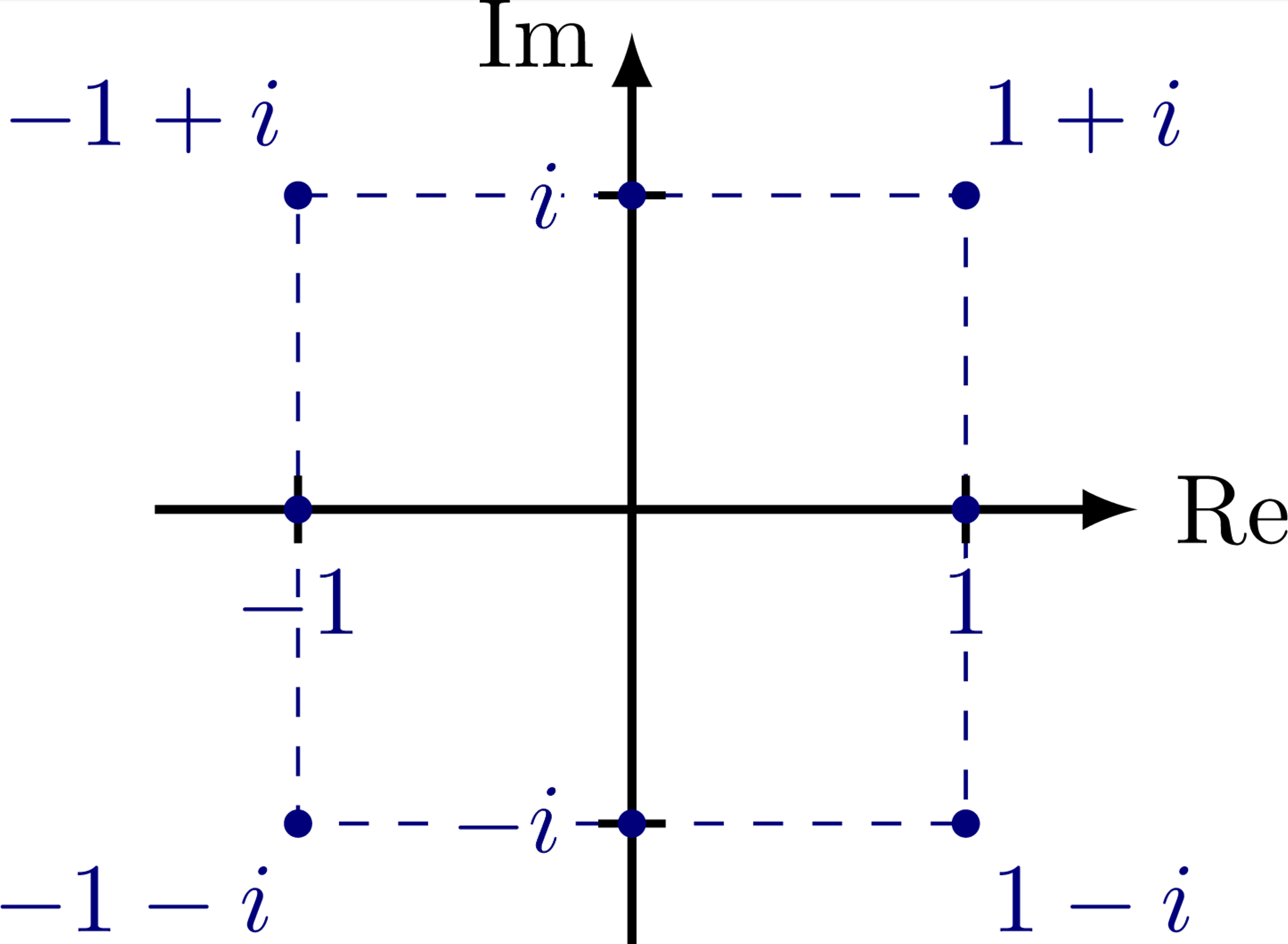

Complex number living in 2D#

A complex number \(z\) is a kind of 2D number that lives in 2D space and requires two components for its full specification. Watch the video to get a visual feel for why we need complex numbers.

Introducing imaginary number \( i \)#

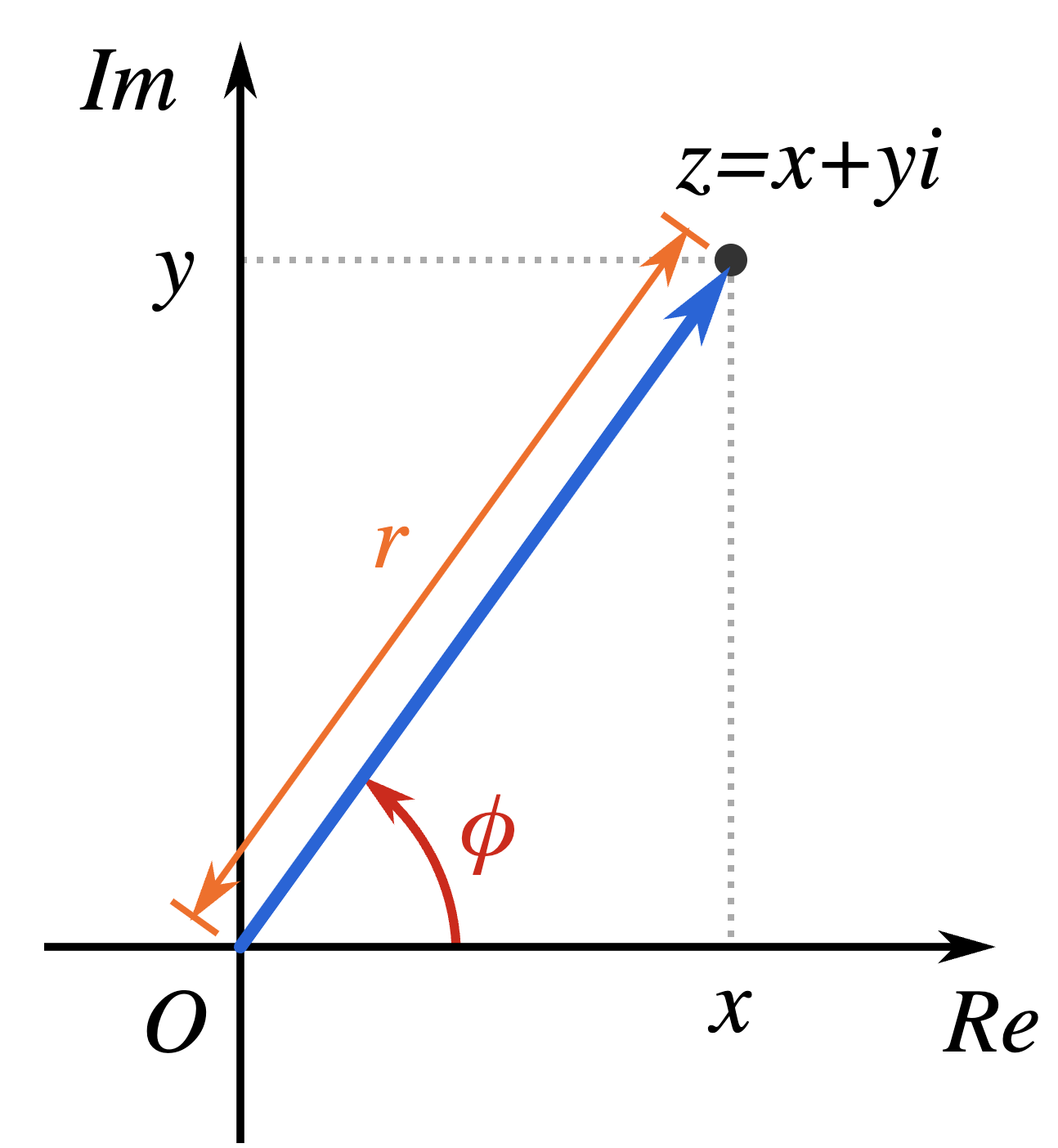

Fig. 108 Visualizing complex numbers on cartesian plane#

Fundamental theorem of algebra. says that polynomial equations like quadratic, cubic, quartic etc must have \(n\) numbers of roots equal to the \(n\)th highest power of the equation. E.g quadratic must have two roots, cubic three, etc. Complex numbers ensure the existence of roots for polynomials.

This equation must have two solutions/roots. How do we visualize them?

The answer: we will need two dimensions! quantifying how much real and how much imaginary component the number has.

What is the definition of \( i \)? The imaginary number \( i \) is defined solely by the property that its square is \(−1\), that is: \(i\cdot i=-1\).

How does \(i\) change what I know about math of real variables? Imaginary numbers extend the real number system \(\mathbb{R}\) to the complex number system \(\mathbb{C}\).

Quadratic Equation Solutions

For a quadratic equation of the form

the solutions are given by the quadratic formula:

The term under the square root, \(\Delta = b^2 - 4ac\), is called the discriminant.

If \(\Delta > 0\): two distinct real roots.

If \(\Delta = 0\): one repeated real root.

If \(\Delta < 0\): two complex conjugate roots.

Fig. 109 Complex numbers live in 2D: You must specify real and imaginary components to fully define a complex number#

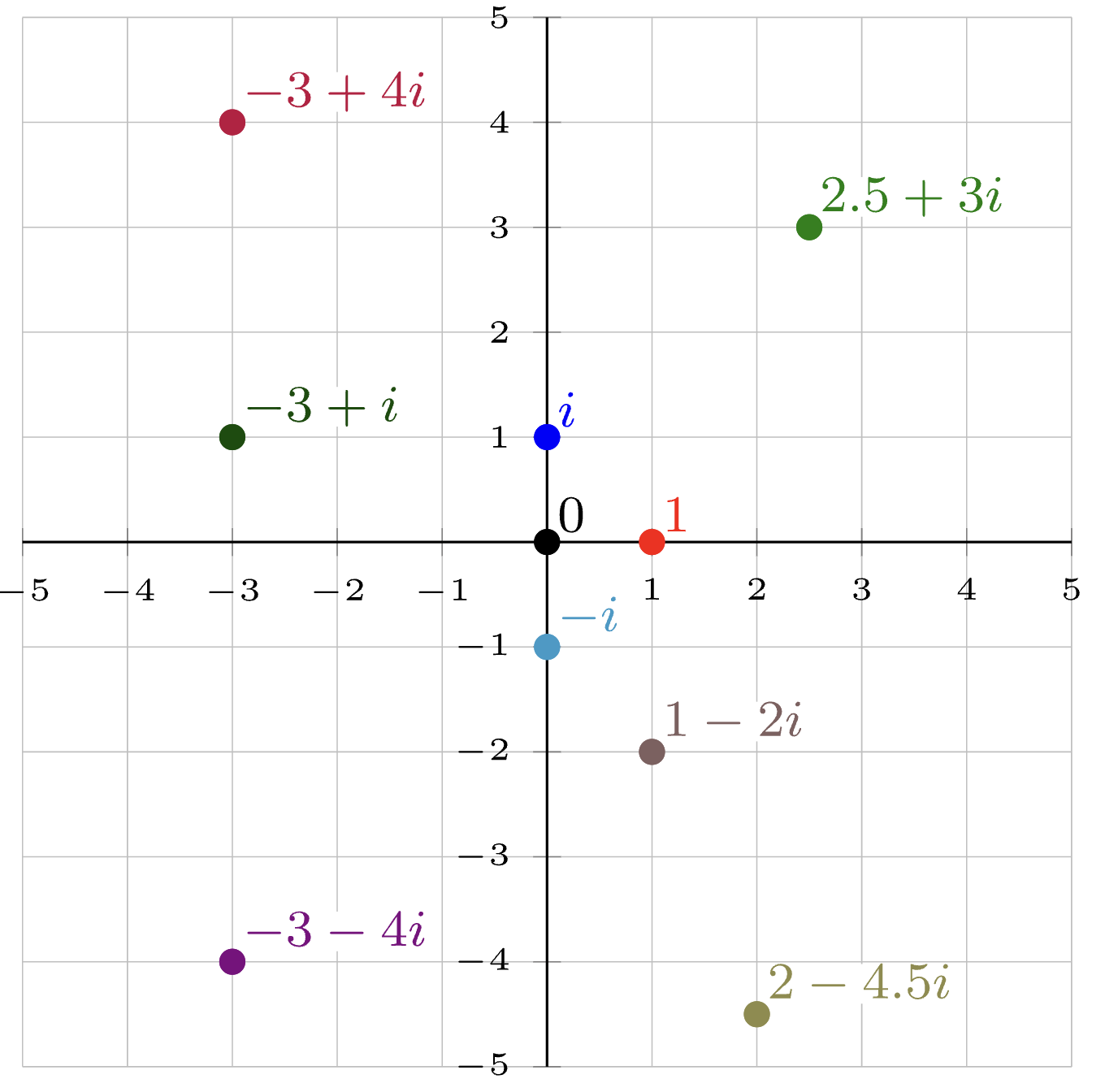

Cartesian vrepresentation#

Fig. 110 Visualizing complaex numbers in cartesian coordinates.#

Cartesian Representation

\(x=Re(z)\) real component

\(y=Im(z)\) imaginary component

Example: Identify real and imaginary parts

Find real and imaginary components of the following complex numbers \(z_1 = 3 +2\), \(z_2 = -2i\), \(z_3=1.1\)

Solution

\(Re(z_1) = 3\), \(Im(z_1)=2\)

\(Re(z_2) = 0\), \(Im(z_2)=-2\)

\(Re(z_3) = 1.1\), \(Im(z_1)=0\)

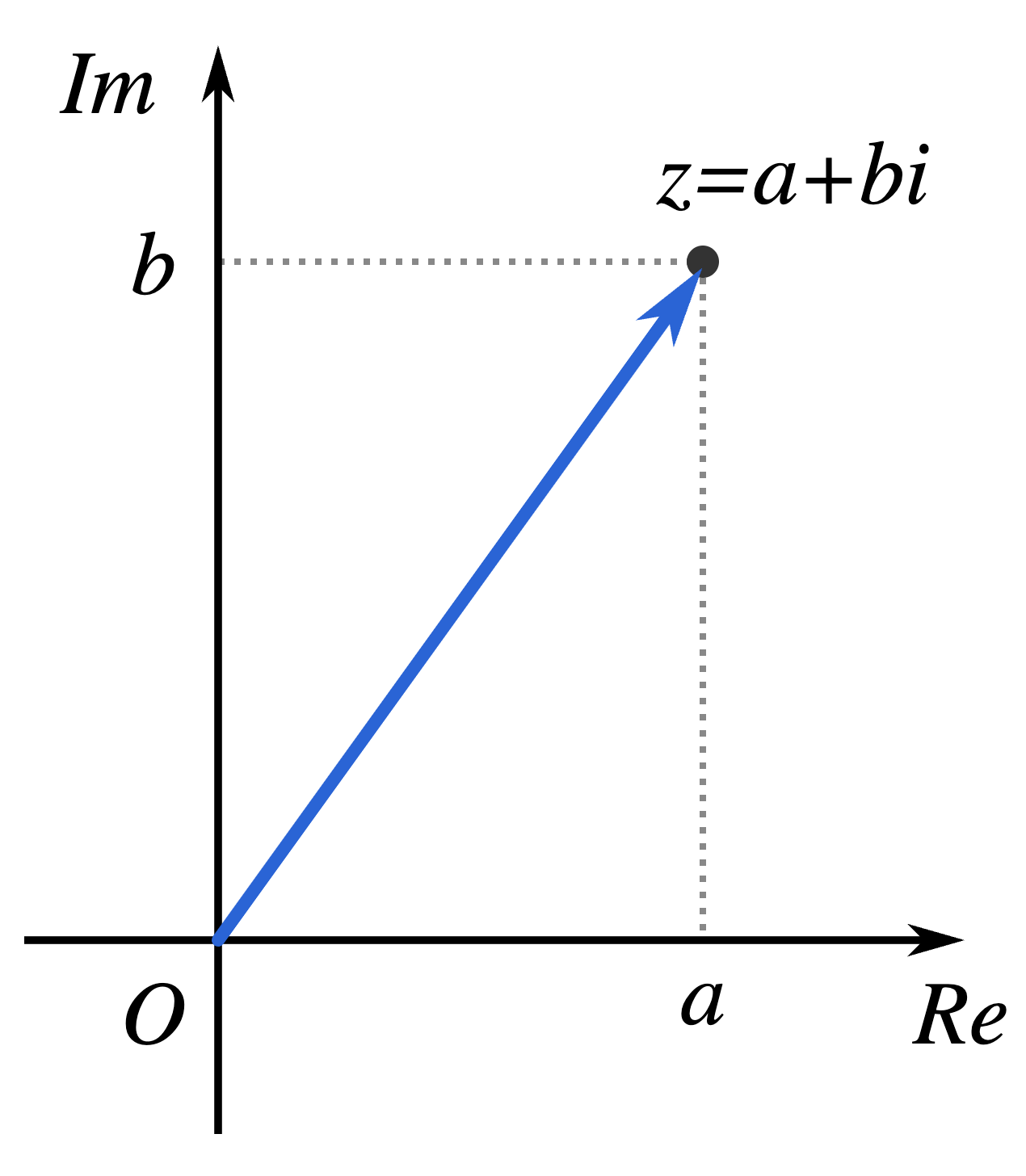

Polar representation#

What’s the big deal with this polar representation? We will find that life is much much easier in polar represnation when deriving new expressions or manipulating complex numbers.

This dramatic simplification is thanks to “magical” Euler’s formula that turns trig functions into exponentss!

Fig. 111 Visualizing complaex numbers in polar coordinates.#

Polar representation expresses complex numbers in terms of radius from origin \(r\) and angle of counterclockwise rotation \(\phi\).

Using trigonometry we have: \(x = r\cos\phi\) and \(y = r\sin\phi\) which can be plugged into cartesian representation:

Polar Representation via sin and cos

\(r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\) distance from origin.

\(\phi\) rotation angle in complex plane.

Euler’s formula

Polar Representation via complex exponential

\(r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\) distance from origin.

\(\phi\) rotation angle in complex plane.

Proof of Euler’s Formula

Consider the exponential and trigonometric Taylor expansions:

Expanding powers of \(i\):

Now separate into real and imaginary parts:

But these are exactly the Taylor series of \(\cos x\) and \(\sin x\). Hence:

Converting from Carteisan to Polar#

Now having established Euler’s formula we need a recepie to go back and forth between cartesian and polar representations.

Extract r The value \(r\) is the Euclidean distance of vector \((x,y)\) from the origin.

Extract \(\phi\) The value \(\phi\) is the angle of with respect to the real axis. The tangent of \(\phi\) is \(\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)\). Therefore using simple trigonometry we can backcalculate angle and sin, cos tan functions from cartesia representatn

Example: Convert to polar

Write complex number \(z = -1-2i\) in polar form

Hot Tip use atan2 or arctan2 in your calculator which correctly identifies quadrant for angle.

Solution

We need to extract \(r\) and \(\phi\) to write \(z= re^{i\phi}\)

We can always add \(2\pi\) to angle we get from arctan2 to make angle positive. Reminder that \(\pm 2\pi \) leave trig functions unchanged.

Fig. 112 Visualization of Euler’s formula \(e^{i\omega t}\) as a function of \(t\). The helix is formed by plotting points for various values of \(\omega\) and is determined by both the cos and sin components of the formula. One curve represents the real component \(cos\omega\) of the formula, while another curve, rotated 90 degrees around the \(t\) axis (due to multiplication by \(i\) represents the imaginary component \(sin\omega\)#

Physical analogy to rotation

Imagine \(e^{i\phi}\) as a spinning wheel where we are rotating angle \(\phi\)

velocity would be given by first derivaive with respect to \(t\) and is equal \(ie^{i\phi}\).

Mulitplicatin by i we know is rotation by 90 degree. Hence velocity is perpendicular or tangential to spinning wheel.

The magnitude of the velocity is \(|ie^{i\phi}|=1\) hence wheel is spinning with constant velocity

The velocity is always tangential to the circular motion, reflecting the nature of rotational movement in the complex plane.

In summary, the complex exponential function elegantly describes both rotation and scaling in the complex plane, and its derivative gives insight into the velocity of rotation, always perpendicular to the position vector.

Complex Conjugate#

Fig. 113 Visualizing conjugate of complex number as a mirror image or rotation backwards#

Complex Conjugate

Extracting absolute value#

Multiplying complex number by its conjugate always results in positive real number!

Geometrically this means rotating back to real axis!

Product of complex number and its conjugate returns the distance from the origin in complex plane.

Expressing sin and cos via complex exponentials#

Using Euler’s formula we can take the sum and difference of \(z\) and \(\bar z\) to express sin and cos in terms of compelx exponentials.

These representations of sin and cos are super powerful in simplifying various integrals and for deriving experssions.

Applications of complex numbers#

De Moivre’s Theorem

De Moivre’s theorem states that:

We raised complex number to power n, used polar representation and realized that exponent raised to power n simply multiplies polar angle by n. Note that de Moivre’s theorem allows relating trigonometric functions of angle \(\theta\) raised to power \(n\) to trignomoteric functions of of angle \(n\theta\) of power one:

The proof of de Moivre’s theorem can be done via induction, e.g one can expand the parentheses ans assert the equality for cases n=2, n=3, …

Deriving Pythagoras’ theorem

We can use de Moivre’s theorem to show that \( r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} \).

We have

and thus

We recognize this as a theorem of Pythagoras.

Deriving Trigonometric Identities

We can obtain a complete suite of trigonometric identities by appropriately manipulating polar forms of complex numbers.

We’ll get many of them by deducing implications of the equality

For example, we’ll calculate identities for \(\cos{(\omega + \theta)} \) and \( \sin{(\omega + \theta)}\).

Using the sine and cosine formulas presented at the beginning of this lecture, we have:

We can also obtain the trigonometric identities as follows:

Since both real and imaginary parts of the above formula should be equal, we get:

The equations above are also known as the angle sum identities.

Evaluating Trigonometric Integrals

We can also compute the trigonometric integrals using polar forms of complex numbers.

For example, we want to solve the following integral:

Using Euler’s formula, we have:

and thus:

Applications to X-ray diffraction and crystalography

Complex numbers play a significant role in various chemistry problems, especially in the context of X-ray diffraction and crystallography. These applications are crucial for determining the atomic structures of molecules and solids.

X-ray Diffraction and the Phase Problem In X-ray crystallography, a crystal is bombarded with X-rays, which are diffracted by the electrons in the crystal. The resulting diffraction pattern contains crucial information about the crystal’s structure. However, to reconstruct the atomic arrangement from the diffraction pattern, we must solve two key problems: the magnitude of the diffracted waves (intensity) and the phase of those waves.

The phase problem refers to the challenge of determining the phase of the diffracted X-rays, which is not directly observable from the diffraction pattern. The phase is necessary to accurately reconstruct the electron density of the crystal.

Complex Numbers in Diffraction To solve this, we model the diffracted waves as complex numbers. Each wave can be described in terms of a complex number:

where:

\(|A(k)|\) is the magnitude of the diffraction wave, corresponding to the intensity of the observed diffraction pattern.

\(\phi(k)\) is the phase of the wave, which contains essential structural information but is not directly measurable.

By representing diffraction waves as complex numbers, we can manipulate and combine them to solve for the electron density in the crystal.

Structure Factor: The Key to Electron Density The structure factor is a complex quantity that relates the electron density in a crystal to the observed diffraction pattern. The structure factor \(F({h})\) is given by:

where:

\({h}\) is the reciprocal lattice vector, representing the direction of diffraction.

\(f_j\) is the scattering factor for atom \(j\) (how much it scatters X-rays).

\({r_j}\) is the position of atom \(j\) in the unit cell.

The structure factor is complex, with both real and imaginary components:

Here, \(|F({h})|\) represents the amplitude (related to the intensity of the diffracted wave), and \(\phi({h})\) is the phase.

Electron Density Calculation Once the structure factors are known, the electron density \(\rho({r})\) can be calculated using the inverse Fourier transform:

where \(V\) is the volume of the unit cell, and the sum is over all reciprocal lattice points \({h}\).

In this equation:

The structure factor \(F({h})\) is complex, and complex numbers allow for the combination of the magnitudes and phases of the diffracted waves to accurately reconstruct the electron density.

The result is a 3D map of the electron density within the crystal, which reveals the positions of atoms.

Solving the Phase Problem

The phase problem is addressed using various techniques, such as:

Direct methods: Mathematical techniques that estimate phases based on probabilistic relationships between structure factors.

Molecular replacement: Using a known structure of a related molecule to estimate phases.

Anomalous dispersion: Utilizing the scattering of X-rays at different wavelengths to provide phase information.

In all these methods, complex numbers are central to solving for the electron density and, thus, determining the molecular structure.

Conclusion In chemistry, particularly in X-ray diffraction and crystallography, complex numbers provide a powerful framework for solving the phase problem and calculating structure factors. They allow for the accurate modeling and manipulation of waves, which are essential for determining the atomic structures of molecules and materials.

Problems#

Problem 1: Multiplication#

Multiply the two complex numbers \(z_1 = 3 + 4i\) and \(z_2 = 1 - 2i\).

Solution 1

To multiply complex numbers, we use distributive property:

Expanding:

Since \(i^2 = -1\):

Problem 2: Find conjugate#

Find the complex conjugate of \(z = -3 + 5i\).

Solution 2

The complex conjugate of a complex number \(z = x + iy\) is given by \(z^* = x - iy\). For \(z = -3 + 5i\), the conjugate is:

Problem 3: from polar to cartesian#

Convert the complex number \(z = 5e^{i\frac{\pi}{4}}\) to its Cartesian form.

Solution 3

Using Euler’s formula:

For \(z = 5e^{i\frac{\pi}{4}}\), we have \(r = 5\) and \(\phi = \frac{\pi}{4}\), so:

Since \(\cos\frac{\pi}{4} = \sin\frac{\pi}{4} = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\), we get:

Problem 4: Division#

Divide the complex numbers \(z_1 = 3 + 4i\) by \(z_2 = 1 - 2i\).

Solution 4

To divide complex numbers, multiply both the numerator and denominator by the conjugate of the denominator:

First, multiply the numerator:

Next, multiply the denominator:

Now, divide the result:

Thus, \(\frac{z_1}{z_2} = -1 + 2i\).

Problem 5: Find Modulus#

Find the modulus of the complex number \(z = 7 + 24i\).

Solution 5

The modulus of a complex number \(z = x + iy\) is given by:

For \(z = 7 + 24i\), we have \(x = 7\) and \(y = 24\):

Thus, the modulus of \(z\) is 25.

Problem 6: Multiplication#

Multiply the complex numbers \(z_1 = 2e^{i\frac{\pi}{6}}\) and \(z_2 = 3e^{i\frac{\pi}{3}}\).

Solution 5

To multiply two complex numbers in polar form, multiply their magnitudes and add their angles:

Thus, the product is:

Problem 7: from cartesian to polar#

Express the complex number \(z = -4 + 4i\) in polar form.

Solution 5

Modulus:

\[ r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} = \sqrt{(-4)^2 + 4^2} = \sqrt{16 + 16} = \sqrt{32} = 4\sqrt{2} \]Argument:

\[ \phi = \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{y}{x}\right) = \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{4}{-4}\right) = \tan^{-1}(-1) \]Since \(z\) is in the second quadrant:

\[ \phi = \frac{3\pi}{4} \]

Thus, the polar form of \(z\) is: